Everything you need to know about the principles of organisation. Organisation is peopled by human beings arranged in relationship with one another.

There are always chances of friction amongst them owing to misconception of authority responsibility, thereby affecting the whole enterprise adversely.

Though such misconceptions are inevitable, they can be minimised. Several management theorists have studied this problem and through their observations, investigations, analysis and experience, have put forward some “principles” for creating a sound organisation.

Some of the principles of organisation are:-

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Delegation of Authority 2. The Scalar Principle 3. Unity of Command 4. Principle of Objective 5. Principle of Division of Labour or Specialisation or Principles of Departmentation

6. Principle of Unity of Efforts 7. Principle of Authority 8. Principle of Responsibility 9. Principle of Definition 10. Principle of Co-Extensiveness

11. Span of Management 12. Principle of Balance 13. Principle of Continuity and Flexibility 14. Principle of Span of Control 15. Principle of Scalar Chain 16. Principle of Absoluteness of Responsibility and a Few Others.

Additionally, some of the the cardinal principles of a sound organisation are:-

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Align Departmental Objectives to Corporate Goals 2. Cost-Effective Operations 3. Optimum Number of Subordinates 4. Specialisation 5. Define Authority 6. Flow of Authority 7. Manage via Exceptional Cases

8. Ensure One Employee, One Superior 9. One Head and One Plan 10. Define Responsibility 11. Commensurate Authority and Responsibility 12. Attain Balance 13. Ensure Flexibility 14. Provide for Continuity.

Principles of Organisation: Division of Labour, Delegation, Scalar Principle, Coordination, Flexibility, Efficiency and a Few Others

Principles of Organisation – 4 Key Principles: Division of Labour, Delegation of Authority, The Scalar Principle and Unity of Command

There are four key principles of organisation. Let us discuss them one by one.

Principle # 1. Division of Labour:

Division of labour (also called the principle of specialization) was first highlighted by Plato in 350 BC when he compared the workmanship of people in small cities with their counterparts in big cities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In his own words:

“Which would be better—that each should ply several trades, or that he should confine himself to his own? He should confine himself to his own. More is done, and done better and more easily when one man does one thing according to his capacity and at the right moment. We must not be surprised to find that articles are made better in big cities than in small. In small cities the same workman makes a bed, a door, a plough, a table, and often he builds a house too…….. Now it is impossible that a workman who does so many things should be equally successful in all. In the big cities, on the other hand……….. a man can live by a single trade. One makes men’s shoes, another women’s, one lives entirely by the stitching of the shoe, another by cutting the leather……… A man whose work is confined to such a limited task must necessarily excel at it.”

The application of division of labour principle can be found in contemporary organisations. The assembly lines in automotive manufacturing have work stations in a sequence and on each work station, a worker performs a highly specialized task. For example, on one work station, a worker fits the head lights to the chassis of the car which comes before his work station on a moving conveyor.

On the next work station, another worker has the sole task of attaching the steering assembly to the car chassis. Yet another worker on the subsequent work station attaches the windshield to the chassis. Thus, workers are semi-skilled and are trained to perform a specialized task.

At the Hero Honda Motors Ltd factories in Gurgaon, Dharuhera, and Harid – war, a mobike comes off the assembly line in every 18 seconds. Naturally, it would not be feasible for any single person to assemble a mobike in just 18 seconds. This signifies the power of the division of labour (also called division of work).

This principle of specialization has major advantages in the form of increased productivity and decreased per unit cost of production for products having less variety. However, it has disadvantages like monotony on part of workers who feel bored of doing the same task over and over again.

This anomaly can be overcome by job rotation of workers (e.g. assigning them to different work stations after every few months) and by job enrichment (e.g. by adding some supervisory duties to the task set of a worker).

Principle # 2. Delegation of Authority:

Authority refers to the rights inherent in a managerial position to give orders and expect the orders to be obeyed. Delegation of authority is the process by which managers allocate authority downward to the people who report to them.

Delegation of authority should be accompanied with responsibility and accountability on part of the manager to whom the authority has been delegated. The manager should feel responsible or obliged to perform the duties assigned to him while using the authority vested in him. Similarly, the manager should be made accountable for the resources consumed by him in the discharge of duties.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

When authority is suitably delegated, it leads to empowerment, in that the people have the freedom to contribute ideas and perform their jobs in the best possible ways.

Principle # 3. The Scalar Principle:

The scalar principle states that there should be a clear and unbroken chain of command or line of authority from the top level of hierarchy to the lowest level by including all intermediate levels. If deprived of such an unbroken chain of command, the benefits of delegation would not be reaped to the fullest possible extent by the organization.

Schermerhorn (2005) contends that higher the number of levels in the hierarchy of the organisation, the overhead costs increase, the communication flow slows down, decision-making becomes tardy and worst of all, the organization may lose contact with the customer. Therefore, a shorter chain of command is preferable by way of lesser number of hierarchy levels in an organization.

Principle # 4. Unity of Command:

Unity of command is another classical management principle which recommends that every individual in the organisation should report to a single boss. This is necessary to avoid confusion on part of the individual if s/he receives directions and orders from more than one superior. The situation may get even more complicated if the individual receives (at times conflicting) instructions from his/her boss and also from the boss’s boss.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In contemporary organisations, however, there is relatively less unity of command due to cross-functional teams, matrix organization structures etc. There are however other benefits in such cases which offset against the confusion resulting due to lesser/lack of unity of command in such scenarios.

Principles of Organisation – Cardinal Principles of a Sound Organisation

The following are the cardinal principles of a sound organisation:

a. Align departmental objectives to corporate goals – It is to be ensured that the objectives of different departments in the organisation are unified and aligned to the corporate goals.

b. Cost-effective operations – An organisation is said to be efficient if it can achieve the goals at the lowest costs and with minimum undesirable consequences.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

c. Optimum number of subordinates – In each managerial position, there is a limit to the number of persons an individual can effectively manage. The optimum number will depend on various factors such as efficiency of the superior and subordinates, the nature of work—routine or special, responsibility, and so on.

d. Specialisation – Similar activities are grouped together to ensure better performance of the work and efficiency at each level.

e. Define authority – The authority and responsibility relationships underlying each position in the organisation have to be defined clearly to avoid confusion or misinterpretation.

f. Flow of authority – This refers to the line of authority from the top management in an enterprise to other levels. If this is clear, then the terms of responsibility also can be understood. Further, this will strengthen the flow of communication to different levels in the organisation.

g. Manage via exceptional cases – An organisation should be geared in such a way that manager’s attention is drawn only to exceptional problems. In other words, a system (such as – organisation manuals) should be developed to take care of routine administration.

h. Ensure one employee, one superior – Each subordinate should have only one superior. There should not be any room for conflict of command.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. One head and one plan – Every group of activities with common objective should be handled by one person and one plan. If handled by different persons, the organisation may lose direction.

j. Define responsibility – A superior is responsible for the omissions and commissions of his subordinates and at the same time the subordinates must be held responsible to their superiors for the performance of the work assigned.

k. Commensurate authority and responsibility – Authority is the right instituted in a position to exercise discretion in making decisions affecting others. The manager occupying that position exercises the authority. Responsibility is the willingness on the part of the employee to be bound by the results.

The authority and responsibility should always be commensurate and coextensive with each other. In other words, if the authority is less than the responsibility, the manager cannot deliver performance of the task and similarly, if the responsibility is less than the authority, the employee may go berserk and unchecked. In other words, the manager cannot discharge his responsibility for want of necessary authority to execute the work assigned.

l. Attain balance – Every organisation needs to be a balanced one. There are several factors such as – decentralisation of authority, delegation of authority, departmentation, span of control, and others, that have to be balanced to ensure the overall effectiveness of the structure in meeting the organisational objectives.

m. Ensure flexibility – The more the flexible structures, the better is the scope to be successful. The principle of contingency endorses this. Where the organisation procedures are cumbersome or rigid, it is necessary to develop an in-built mechanism to forecast any type of constraint.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

n. Provide for continuity – The organisation structure should provide for the continuation of activities. There cannot be any breakdown in the activities of the organisation for the reasons such as – a change in the policies or retirement or death of any key employee in the organisation.

Principles of Organisation – 10 Principles of Organisation according to Urwick

Organisation is peopled by human beings arranged in relationship with one another. There are always chances of friction amongst them owing to misconception of authority responsibility, thereby affecting the whole enterprise adversely. Though such misconceptions are inevitable, they can be minimised.

Several management theorists have studied this problem and through their observations, investigations, analysis and experience, have put forward some “principles” for creating a sound organisation. Taylor, Fayol and Urwick have embodied their experience into a set of principles; especially Urwick has laid down a set of “Ten Principles” as a measure of sound organisation.

These principles are:

1. Principle of Objective:

The organisation as a whole as well as its parts must have a clear-cut idea about the objectives of an enterprise. Every organisation is evolved for a specific purpose. It does not exist in a vacuum. Every part of the organisation and the organisation as a whole must be geared to the objectives laid down for the enterprise. This will secure unit of objectives.

2. Principle of Division of Labour or Specialisation or Principles of Departmentation:

The workload is so divided that each member of the organisation is called upon to perform a single function. Overburdening as well as entailing diverse duties must be avoided. Aptitude of the employee must be considered while assigning him a specific job. If a man fits into a job, his productivity enhances.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It thereby maximises the productivity of an enterprise as a whole. Most efficient break down of activities reflecting proper departmentalisation is a must for a sound organisation. The term “departmentation” stands for the division and classification of an industrial enterprise into several distinct departments or sections.

It helps in fixing definite responsibility, in measuring the efficiency of each functional performance, in drawing departmental budgets accurately, in obtaining true departmental costs in manpower planning and in controlling the whole spectrum of activities of the organised unit.

3. Principle of Unity of Efforts:

For the good performance of different activities, the enterprise itself is divided into a number of divisions, departments and sections. Though there are different divisions, departments and sections carrying out specific activities, all these activities ultimately aim at bringing the unity of efforts. Coordination is necessary there to move in the direction of the given objectives. It will avoid bottlenecks, frictions, conflicts and rivalries.

4. Principle of Authority:

The chain of command, i.e., the line of authority, must be well defined so that every subordinate knows who is his superior. The authority of different individuals, at different levels, must be spelt out. Who shall take a decision, issue instructions, recruit staff, control work, must be fixed in advance.

Then only can the work be carried out by the subordinates as planned. There should never be confusion as to whom to report or refer to for decisions. There are different levels of authority in an organisational structure from the top executive to the worker.

The scalar principle maintains that these levels represent gradation of distributed authority, each successive level downward representing a decreasing amount of authority, a decreasing scope of authority and often a different kind of authority. This is important in the sense that it sheds light on the way in which the different parts of an organisation are created and held together. Moreover, it also helps in understanding the authority relationships in the organisation.

5. Principle of Responsibility:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A superior is always responsible for the success or failure of his subordinates. It means the responsibility can never be delegated, though authority can percolate from upwards to downwards. In any organisation, the superior is held responsible for the actions of his subordinates and the subordinates are accountable for the work to their superiors.

6. Principle of Definition:

There are authority-responsibility relationships in an organisation. The scope of authority and responsibility must be spelled out in definite terms. Everyone in the organisation must clearly know what his authority is and what his responsibility is and how he stands in relationship with other positions in it.

7. Principle of Coextensiveness:

The authority and responsibility must be coextensive and coterminous. For the discharge of responsibility, a subordinate must be given adequate authority. Authority without responsibility will make him irresponsible, while responsibility without authority will make him impotent. Responsibility can be carried out effectively only with adequate authority.

8. Span of Management:

The span of management is the number of subordinates that a manager can supervise. The basic questions surrounding the span of management are- (1) How many subordinates should be assigned to a superior, and (2) Should the organisational structure be “wide” or “narrow?” The types of organisational structure involved in each instance.

Generally speaking, the effort to identity a specific number or range of subordinates has not been productive. In practise, the number varies widely.

Factors that Determine the Best Span for a Manager:

The span of management appears to depend on the manager’s ability to reduce the time and frequency of subordinate relationships.

These factors, in turn, are determined by-

(1) How well the subordinate is trained to do his job;

(2) The extent of planning involved in the activity;

(3) The degree to which authority is delegated and understood;

(4) Whether standards of performance have been set;

(5) The environment for good communications; and

(6) The nature of job and the rate at which it changes.

Span of control has attracted much attention from the writers on organisation. An organisation’s success undoubtedly rests heavily on the abilities of the organisational people, and so there is need for avoiding overburdening managers with supervisory responsibility. It calls for the search of a maximum number of subordinates that one man should be asked to supervise.

The span of control principle merely acts as a check to see whether the intended groupings are “manageable”. It depends not only on the number of subordinates that the manager of the grouping must supervise but also on the nature of the activities in the grouping, the cooperation among the subordinates, the abilities of the particular manager and many other factors.

The strongest arguments that have advanced to support a limited span of control have a theoretical rather than a practical basis. Graicunas, the French mathematician and consultant, puts forward a theoretical formula for determining the span of control.

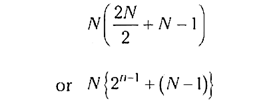

The possible total number of “relationships”, according to Graicunas, can be found from the following formula-

Where N- number of subordinates.

According to this formula, where there are only two subordinates, there could be six relationships, where there are- subordinates, there could be as many as one thousand and eighty relationships, all of which could demand the attention of the supervisor. This formula is quantitative rather than qualitative.

The theory is amenable to criticism since it ignores the fact that the complexity of the supervisor’s task varies with the organisational level. A greater span of control is possible at the lowest level.

It is important to avoid the overburdening of the manager by limiting his span of control. However, while doing so, we lengthen, the chain of command and increase the organisational levels. There are consequential problems of communication and motivation. The matrix of departmental objectives becomes more complex.

Promotion comes at a dead slow speed and loses its motivational value, so the need to limit the span of control must be carefully weighted against the benefits of reducing the number of organisational levels.

In the case of managers who are reluctant to delegate, increasing the span of control gives positive benefits. It is necessary to appreciate the benefits than can be gained by increasing rather than restricting the span of control.

Factors Relevant in Determining Span of Control:

(a) The ability of the manager and the amount of work other than supervision he has to do. It is often overlooked that supervision is only a part of a manager’s total function. It is increase the number of his subordinates, therefore, his workload increases, but not in the same proportion.

(b) Span of control is affected by the supervisory needs of the subordinates. It, in turn, depends upon the competence of subordinates and on the group behaviour — whether co-operative or conflicting. It also depends on how much their jobs have been simplified by a good information system and routine decision making. Moreover, where the jobs of subordinates are very similar, their supervisory needs will also be similar, and so they will make smaller demands on the supervisor’s time.

(c) Personal assistants can be used to relieve managers of specified duties.

Spans of Control are Limited:

At high levels the responsibility in the company are great and the work assignments are broad and general so the span is small (often between 5 and 9). At lower levels, the responsibilities are more limited and work assignments are detailed and specific but they don’t change often and so spans can be larger (often they are between 20 and 30).

What factors affect the proper number of men that a man should supervise? First is the complexity of the work being supervised? At the bottom of the organisation, men usually work on highly structured jobs which need directions only at the start of a job. Once the worker learns his job, a machine operator, for example, he needs little supervision.

How many man one foreman can supervise depends upon both-

(1) The complexity of the work, and

(2) The frequency of new work assignments. Besides these two conditions, there are at least two more factors which affect the span of control;

(3) The ability of people being supervised; and

(4) How much time the foreman spends on non-supervisory work.

The maintenance department foreman has rarely to tell his electricians how to put up a light fixture or his roofers how to repair a leaky roof because they know how. Factory foreman often do not have to explain jobs to their experienced workers either. Their being skilled lessens the amount of supervision and allows the foremen to supervise more men.

The span also depends upon partly on how good a trainer the foreman is. If he trains his men well, he can supervise more men. It also depends on labour turnover. If there is a high turnover, he has more training to do and so can’t supervise so many.

A foreman’s span of control (or anyone else’s) depends also on his non-supervisory duties. Nearly always he must keep records, make reports, attend meetings, confer with his superior, with staff men, and with other departmental heads. All of this takes time. The more time he spends on non-supervisory work, the less he has for supervising and the fewer people he can supervise.

Wide Spans:

Not all companies go along with small numbers at the top. Some exceed the usual spans. Sears, Roebuck and Johnson and Johnson each use a wider span. Sears has 13 vice-presidents reporting to its president, Johnson and Johnson has more. These two companies are among a minority, however, in favouring wide spans at the top.

Wide spans at the top do, of course, result in fewer managers and fewer layers of managers. If one president supervises 15 divisional heads who each supervises 20 foremen, who in turn each supervises 25 operatives, you have an organisation with 7,500 men at the bottom level, or 7,816 altogether (inducing 316 supervisors); yet there are only two levels of supervision between the president and the 7,500 bottom-level employees.

Wide spans reduce layers and require fewer executives. If the spans in our example were cut to 10, 15, and 20, another layer of supervision would have to be introduced and we would have to go up to 411 supervisors and executives. This way it takes 95 more supervisors. Eliminating 95 supervisors is a big payroll saving.

We can use the span of control ideas as a management control either to check on existing organisation or to plan a new one. Several years ago, Ralph C. Davis expressed span of control relationships in formula form (as they relate to the line organisation only, since the size of staff departments is less affected by the span of control concept).

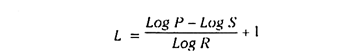

We start with the question- For any given number of operatives and for any selected span, how many levels of supervision will be needed?

Let

P = Number of primary operatives.

S = Span of control for foremen.

R = Span of control above the foreman level.

L = Number of levels of supervision, including the top man as one level.

Then-

Formula 1:

Consider as an example an organisation of 7,500 operatives with a span of 15 for men and 5 for all higher executives.

Then,

Five levels will be needed throughout most of the organisation although some parts will be able to operate with only four levels or five levels could be used throughout the whole organisation and the spans reduced a little in a few places.

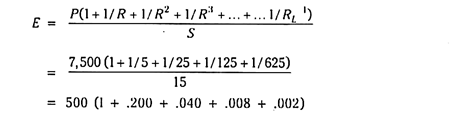

Having, found the number of levels needed we can now find how many executives are needed.

Let

E = the number of executives

Then-

Formula 2:

= 500 (1.25)

= 625

The answer is, of course, only approximate because 4.86 levels; rounded to 5.

Payroll Savings:

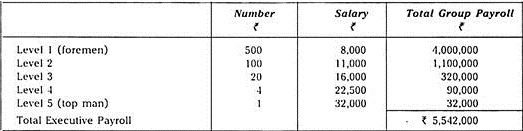

If the primary operatives earn an average of Rs.4,500 a year and we want to pay supervisors about 40 per cent more than their subordinates average earnings then, for our executive payroll will shape up like this-

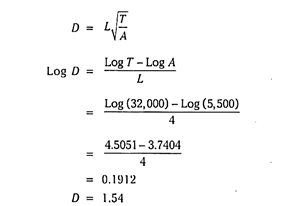

Just how much do flat spans save? If we substitute a span of 20 for foremen and 7 for all higher levels we will find that only four levels and about 436 executives are required. If we spread the salaries proportionally between Rs.5,500 factory workers and Rs.32,000 top, we can find the approximate salaries for each level. To calculate this ratio-

Let

T = salary of the top executive.

A = average earnings of operatives.

D = ratio between salaries of levels.

Then-

Formula 3:

Each supervisor’s rate needs to be about 54 per cent higher than the average of his subordinate.

This policy would result as follows:

Pros and Cons of Flat Spans:

Payroll saving is not the whole story of span of control. If it were, everyone would go in for wide spans. But before we get to the disadvantages of wide spans, there are other advantages. Wide spans prevent over supervising. A subordinate in a wide-span company just has to make his own decisions because his boss doesn’t have much time to spend with him.

Making his own decisions helps him to develop. It is essentially a sink or swim situation. Each man goes it on his own and stands or falls on his own performance. Men who succeed are better men for the experience. Those who fail are shunted off into less demanding jobs.

Flat-span companies claim that they have higher morale because department heads have real decision making authority. They are not themselves overspecialized, nor are they hampered by the interference of specialists.

Distances from top to bottom, organisation-wise, are short. Communication is claimed to be easier; top officials understand work-level problems better. This may not be so, however. If there are twenty reporting to a vice-president, he isn’t going to have time to hear much about their problems.

The arguments favouring flat organisations seem good. Why aren’t such organisations common? First, it loses a degree of control. We don’t know what our subordinates are doing when we have so many that you can’t keep track of them. Some do their work well, some not so well. By the time we find out, they have lost considerable money for the company.

Secondly, no time is left for non-supervisory part of the work.

Third, when subordinates have to sink or swim, some of them sink. When you find out that they aren’t doing well, you can replace them, but replacing is costly and hurts everyone’s morale. Besides, some of them learn to swim, but not well. Self-made men don’t always make a very good product.

Common practice, therefore (narrow rather than wide spans), has a good many advantages which probably more than offset the advantages of flat spans.

9. Principle of Balance:

An organisation is made up of different units. All these units should be kept in balance. Each function should be given its proper emphasis with regard to its basic purpose in the organisation. Moreover, a good organisation must be balanced with respect to centralisation and decentralisation, authority and responsibility, span of control and line of communication.

Giving dominion to one activity over the other will hamper smooth and balanced working of an organisation. The object of this principle is that each portion and function of an enterprise should operate with equal effectiveness in making its allotted contribution to the total purpose.

An organiser must assume the responsibility of ensuring a reasonable balance of the vertical and horizontal dimensions of his structure. A growing business takes into its stride new departments and new levels. There is, however, a strong temptation to go too far in either direction with the result that the line of communication is unduly lengthened and overhead expenses are increased.

“The final result is that instead of higher efficiency and greater profit expected from specialisation, there is a lower overall efficiency and lower profit. It is, therefore, necessary to take care, particularly in a growing organisation, to see that the organisational structure does not become extremely tall or flat and to ensure that its dimensions are in a reasonable balance.”

10. Principle of Continuity and Flexibility:

An organisation is a continuous process. The organisational structure must adopt itself to the environmental changes. As the enterprise grows, its activities become varied and complex. The existing organisational structure must be flexible enough to incorporate such a growth.

It must be able to adapt readily to the technological and business changes. Reorganisation is a sign of a continuous and dynamic organisation. No company is static. Its goals may change for many reasons.

For each such change, there should be a concomitant modification in the organisational structure, it means that the organisational structure should be such as to provide not only for the activities immediately necessary to secure the objectives of the enterprise but also for the continuation of such activities in the foreseeable future.

In addition, a good organisation must incorporate the following principles:

(а) Unity of Command:

According to this principle, an employee receives orders only from one superior officer and none else. He is responsible only to one particular superior and to none else in the organisation. If two superiors exercise their authority over the same individual or department, there is going to be confusion.

In order to expedite decisions and, at the same time, to prevent the consequences of dual command, Urwick has recommended the device of the Gang Plank. It means that two or more supervisors may authorise their immediate subordinates to settle directly certain matters but require that they will be kept informed.

The principle of unity of command, in other words, reduces to “no man will serve to two masters”. It avoid conflict and frictions arising out of dual commands. It also helps effective communication.

(b) Unity of Direction:

The total work is divided and subdivided. The activities are classified and grouped. For each group, of activities, there must be only one plan and the efforts must be towards one and the same end. This will help removal of conflicts and confusion.

(c) Exception Principle:

The principle states that the routine matters should be left to the subordinates while only important matters (policy matters) be left to the executive. One cannot imagine an executive concentrating on routine matters and allowing less time for deciding on policy matters.

The executive must not be burdened with routine matters which can be easily dealt with by the subordinates. The executive must be able to concentrate on important matters and perform the managerial functions. Only those matters which are exceptions to routine matters will be referred to the executive.

(d) The Principle of Simplicity:

It means that an organisation should strive for structural simplicity for fulfilling the purpose in mind. It provides the company an economically effective means of accomplishing its objective. Simplicity helps in the minimisation of the fixed costs and eases out the difficulties arising from the complicated organisational structure.

Principles of Organisation – 14 Principles

1. Principle of Objective:

An organisation and every part of it should be directed towards the accomplishment of basic objectives. Every member of the organisation should be well familiar with its goals and objectives. Common objectives create commonness of interests.

In the words of Urwick, “Every organisation and every part of the organisation must be an expression of the purpose of the undertaking concerned.” The application of this principle implies the existence of clearly formulated and well-understood objectives. An organisation structure must be measured against the criterion of effectiveness in meeting these objectives.

2. Principle of Division of Work:

The total task should be divided in such a manner that the work of every individual in the organisation is limited as far as possible to the performance of a single leading function. The activities of the enterprise should be so divided and grouped as to achieve specialisation. However, the principle of division of work does not imply occupational specialisation. The allocation of tasks should be on the basis of qualification and aptitude and should not make work mechanical and boring.

3. Principle of Unity of Command:

Each person should receive orders from only one superior and be accountable to him. This is necessary to avoid the problems of conflict in instructions, frustration, uncertainty and divided loyalty and to ensure the feeling of personal responsibility for results. This principle promotes co-ordination but may operate against the principle of specialisation.

4. Principle of Span of Control:

No executive should be required to supervise more subordinates than he can effectively manage on account of the limitation of time and ability. There is a limit on the number of subordinates that an executive can effectively supervise. However, the exact number of subordinates will vary from person to person depending upon the nature of job, and basic factors that influence the frequency and severity of the relationships to be supervised.

5. Principle of Scalar Chain:

Authority and responsibility should be in a clear unbroken line from the highest executive to the lowest executive. As far as possible, the chain of command should be short. The more clear the line of authority from the ultimate authority in an enterprise to every subordinate position, the more effective will be decision-making and organisation communication.

6. Principle of Delegation:

Authority delegated to an individual manager should be adequate to enable him to accomplish results expected of him. Authority should be delegated to the lowest possible level consistent with necessary control so that co-ordination and decision-making can take place as close as possible to the point of action.

7. Principle of Absoluteness of Responsibility:

The responsibility of the subordinate to his superior is absolute. No executive can escape responsibility for the delegation of authority to his subordinates.

8. Principle of Parity of Authority and Responsibility:

Authority and responsibility must be co-extensive. The responsibility expected for a position should be commensurate with the authority delegated to that position, and vice-versa. In addition, authority and responsibility should be clearly defined for all positions.

9. Principle of Co-Ordination:

There should be an orderly arrangement of group efforts and utility of action in the pursuit of a common purpose. This would help in securing unity of effort.

10. Principle of Flexibility:

The organisation must permit growth and expansion without dislocation of operations. Devices, techniques and environmental factors should be built into the structure to permit quick and easy adaptation of the enterprise to changes in its environment. Good organisation is not a straight jacket.

11. Principle of Efficiency:

An organisation is efficient if it is able to accomplish predetermined objectives at minimum possible cost. An organisation should provide maximum possible satisfaction to it members and should contribute to the welfare of the community. The principle of efficiency should be applied judiciously.

12. Principle of Continuity:

The organisation should be so structured as to have continuity of operations. Arrangements must be made to enable people to gain experience in positions of increasing diversity and responsibility.

13. Principle of Balance:

The various parts of the organisation should be kept in balance and none of the functions should be given undue emphasis at the cost of others. In order to create structural balance, it is essential to maintain a balance between centralisation and decentralisation, between line and staff, etc. Vertical and horizontal dimensions must be kept in reasonable balance by ensuring that the structure is neither too tall nor too flat.

14. Principle of Exception:

Every manager should take all decisions within the scope of his authority and only matters beyond the scope of his authority should be referred to higher levels of management. In other words, routine decisions should be taken at lower levels and top management should concentrate on matters of exceptional importance.

Principles of Organisation – 15 Principles of a Sound Organization Structure

Sound organization structure is an essential pre-requisite of efficient management. It depends upon certain established principles which must be kept in mind while establishing and developing organizational structures.

The most important of them are as follows:

(1) The Principle of Unity of Command:

Henry Fayol, a French Management theorist, deserves credit for publicising the principle of unity of command, but, no doubt, the idea had occurred to many managers long before his time. The basic idea is that no member of an organization should report to more than one superior. If two superior bosses wield their authority over the same individual or department, everything will be in disorder.

The boss by-passed will naturally feel irritated and there would be hesitation on the part of the subordinate. In order to ensure quick action and at the same time to prevent the consequence of dual command, Urwick has recommended the device of Gang Plank. It means that two or more superiors may authorise their immediate subordinates to settle directly certain matters but require that they will be kept informed of what has been agreed to by the latter.

It holds that in every organization there must be an ultimate authority from which a clear authority must be derived to every subordinate position in organization.

Some advocates of the Scalar Principle imply that most organizations could place greater stress on hierarchy, and greater stress on definition of responsibilities up and down the line. When applied this way the scalar principle becomes controversial. The extent to which definition of responsibilities is productive, are matters of degree on which this principle is unclear. In planning an organization it may be appropriate to begin with the vertical structure of authority, but this provides little guidance in determining what the character and extent of that authority should be.

(3) The Span of Control Principle:

This is also known as Span of Management Principle. Like unity of command, the famous principle of span of control arouses doubt when expressed in an extreme form. The principle states that there is a limit to the number of subordinates that should report to one superior. Some writers state precisely that five or eight people are the maximum number one man can supervise.

Supervision of too many people can lead to trouble. The superior will not have the time to devote to any one subordinate to do an adequate job of supervision. He may be distracted by the large number of contacts required in his position so that he neglects important question of policy. Some theorists have pointed out that as the number of people reporting to a superior increase arithmetically, the number of possible interrelationships among them and with the superior increases geometrically, rapidly reaching a point at which the structure becomes too complex for management by single individual.

The appropriate span depends upon a number of considerations. It is easy to supervise a large number of subordinates doing routine jobs and located in a single room; but it is difficult to supervise highly diverse and specialized personnel scattered widely geographically. The ability of the employees, their willingness to assume responsibility, and the general attitude of management towards delegation and decentralization, should influence the decisions on span of control.

(4) The Management by Exception Principle:

F. W. Taylor advocated another widely accepted generalization-the Exception Principle. According to this concept, decisions which frequently should be reduced to a routine and delegated to subordinates, leaving more important issues and exceptional matters to superiors.

(5) The Principle of Unity of Objective:

It holds that each part and sub-division of the organization should be the expression of a definite purpose in harmony with the objective of the undertaking.

(6) The Principle of Unity of Direction:

There must be only one plan for a group of activities directed towards the same end. If each person in a department begins to work under a different plan or programme of action, nothing but confusion will follow. Unity of direction is a ‘must’ for sound organization.

(7) The Principle of Simplicity:

Simplicity should be an objective of organizational planning. It is, however, a relative term. It means that an organization should strive for structure which is the simplest possible and yet, will fulfil the purposes intended and provide for economic and effective means of accomplishing desired objectives. Simplicity helps in the minimization of the overhead costs and reduces the difficulties that may arise due to complicated organization structure.

(8) The Principle of Continuity:

It means that the organization structure should be such as to provide not only for the activities immediately necessary to secure the objectives of the enterprise but also for the continuation of such activities the foreseeable future.

(9) The Principle of Ultimate Authority:

The responsibility of a higher authority for the act of its subordinates is absolute. Hence delegation of authority does not entail resignation of responsibility.

(10) The Principle of Parity of Authority and Responsibility:

The responsibility for the execution of work must be accompanied by the authority to control and direct the means of doing the work.

(11) The Principle of Assignment of Duties:

The duties of every person in an organization should be confined as far as possible to the performance of a single leading function.

(12) The Principle of Definition:

The duties, authority, responsibility and relations of everyone in the organizational structure should be clearly and completely prescribed in writing.

(13) The Principle of Homogeneity:

An organization, to be efficient and to operate without friction, should be so designed that only duties and activities that are similar or are directly related are combined for execution by a particular individual or particular group.

(14) The Principle of Authority-Level:

In every organization there should be some level in which authority for decision must reside. And only decisions that cannot be made at a given level must be referred to upward levels.

(15) The Principle of Organization Effectiveness:

The final test of an industrial organization is smooth and frictionless operation. Organization should determine the selection of personnel; rather than personnel determine the nature of organization.

A member does not, by delegation, divest himself of responsibility. Two members should not delegate responsibility to the same member.