Sylos-Labini developed a model of limit-pricing based on scale-barriers to entry. His model is clumsy, due to its unnecessarily stringent assumptions and the use of arithmetical examples.

However, his analysis of the economies-of-scale barrier is more thorough than that of Bain. He highlighted the determinants of the limit price and discussed their implications, thus providing the basis for Modigliani’s more general model of entry-preventing pricing.

Sylos-Labini concentrated his analysis on the case of a homogeneous oligopoly whose technology is characterised by technical discontinuities and economies of scale.

Assumptions:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. The market demand is given and has unitary elasticity. The product is homogeneous and will be sold at a unique equilibrium price.

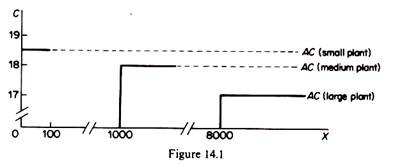

2. The technology consists of three types of plant a small plant with a capacity of 100 units of output; a medium-size plant with a capacity of 1000 units of output; a large-size plant with a capacity of 8000 units of output. Each firm can expand by multiples of its initial plant size only. That is, a small firm may expand by installing another small plant a medium firm may expand by setting up a second medium-size plant, and so on. There are economies of scale cost decreases as the size of the plant increases. However, with this rigid technology we cannot construct a continuous LRAC curve. We have three cost lines corresponding to the three plant sizes (figure 14.1).

3. The price is set by the price leader who is the largest firm, with the lowest cost (ex hypothesis) at a level low enough to prevent entry. The smaller firms are price-takers. Each one individually cannot affect the price. However, collectively they may put pressure on the leader by regulating their output. Thus the largest firm does not have unlimited discretion in setting the price it must set a price that is acceptable to all the firms in the industry as well as preventing entry.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. There is a normal rate of profit in each industry. (Sylos, in his example, assumed that the rate of normal profit is 5 per cent.)

5. The leader is assumed to know the cost structure of all plant sizes, and the market demand.

6. The entrant is assumed to come into the industry with the smallest plant size.

7. The established firms and the entrant behave according to what Modigliani called the ‘Sylos’s Postulate’. This includes two behavioural rules, one describing the expectations of the established firms and the other the expectations of the entrant. Firstly, the existing firms expect that the potential entrant will not come into the market if he thinks that the price post-entry will fall below his LAC.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Secondly, the entrant expects that the established firms will continue in the post-entry period to produce the same level of output as pre-entry. Under these assumptions, as entry takes place the market price falls and the whole of the resulting increase in the quantity demanded accrues to the new entrant. Clearly this is the same as Bain’s Model B.

Sylos does not give any reason for this behavioural pattern. The rationalization of the Sylos’s postulate has been discussed by subsequent writers.

The model:

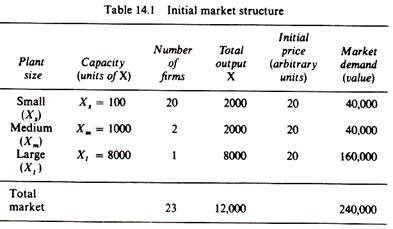

Sylos-Labini presents his model with a numerical example. He starts with the market structure shown in table 14.1 which is assumed to be created at random, and proceeds to examine how equilibrium is attained in this market. The equilibrium at price 20 is not stable, because the market output is too small and the price is too high, so entry will take place.

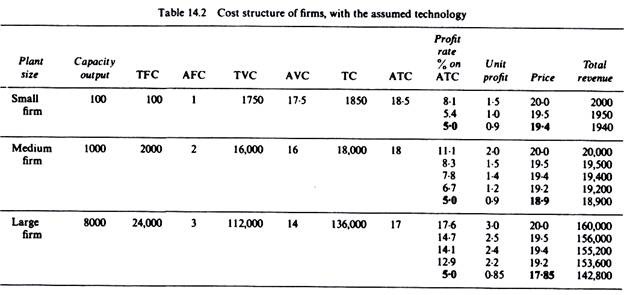

This is due to the fact that, given the cost structure of the three plants in the industry (see table 14.2), the profits are too high for all firms at the price of 20. From table 14.2 it is apparent that the profit rate of the small firms is 8.1 per cent of the medium firms 11.1 per cent and of the large firms 17-6 per cent. These rates are higher than the minimum profit rate (normal profit) of the industry which is assumed to be 5 per cent. The excess profits will attract entry. Under the above rigid assumptions regarding technology, the possibility of expansion of the existing firms by multiples of their initial plant size and the unitary elasticity of demand, the following results emerge.

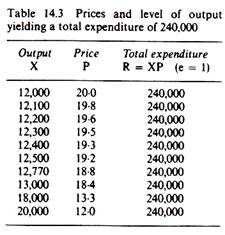

No new large firm will enter into the industry. If it did, total sales would rise to 20,000 units and the price would fall to 12, a level lower than the minimum acceptable price to any firm in the industry. From table 14.2 we can see that the minimum acceptable prices for the three plant sizes are 19-4 (for the small plant), 18-9 (for the medium size plant) and 17-85 (for the large scale plant).

Even the entry of a new medium-size firm is precluded given the costs and the demand in the industry. If a medium-size plant were installed sales would increase to 13,000 units, and the price would fall to 18-4, which is not acceptable by the small and the medium- size firms.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, up to three small firms can enter the market. Their entry would cause sales to rise to 12,300 units and the price to fall to 19-5, which exceeds the minimum acceptable price of all firms. The entry of a fourth small firm would depress the price to 19-3, a level below the minimum acceptable price (of 19-4) of the small firms.

Thus the entry-forestalling price is just above the minimum acceptable level of the smallest, least efficient firms.

The above results regarding the entry conditions under the given cost and demand conditions are shown in table 14.3. The computations are based on the assumption that the demand has unitary elasticity so that the total expenditure is the same (equal to the initial level of 240,000) at all prices.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Price determination:

We said that the price is set by the largest, most efficient firm. The equilibrium price must be acceptable by all the firms in the industry, and should be at a level which would prevent entry. Given that firms have different costs, there are as many minimum acceptable prices as plant sizes. For each plant the minimum acceptable price is defined on the average-cost principle

Pi = TACi(1 + r)

where Pt = the minimum acceptable price for the ith plant size

ADVERTISEMENTS:

TACi = total average cost for the ith plant size

r = normal profit rate of the industry

The minimum acceptable price covers the TAC of the plant and the normal (minimum) profit rate of the industry (in Sylos’s example r = 5 per cent for all plant sizes, that is, the normal profit of the industry is 5 per cent). The price leader is assumed to know the cost structure of all plant sizes and the normal (minimum) profit rate of the industry. Given this information the leader will set the price that is acceptable by the smallest, least efficient firms, and will deter entry.

The price tends to settle at a level immediately above the entry preventing price of the least efficient firms, which it is to the advantage of the largest and most efficient firms to let live. The price leader, which is the most efficient firm, will set the price at a level acceptable to all existing firms and low enough to forestall entry. Entry takes place with the minimum plant scale which has the highest cost.

In Sylos’s model, where differential costs are assumed, the price, in order to be a long-run equilibrium one, apart from preventing entry must also be acceptable by the least efficient firms, allowing them to earn at least the normal industry profit given that the most efficient firm (leader) does not find it worthwhile to eliminate the smaller firms, either because such action is not profitable or because the leader is afraid of attracting government intervention due to high concentration in the industry.

Clearly the medium and large-scale firms, having lower costs, will be earning abnormal profits. But small firms will also normally be earning some abnormal profits without attracting entry. Given the market demand at the minimum acceptable price of the smallest least efficient firm (and given that at that price all established firms work their plants to full capacity), the price leader will set the price at such a level, that, if the entrant decides to enter, the market price will fall below his minimum acceptable price (which is the same as the minimum acceptable price of the smallest, least efficient plant size).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

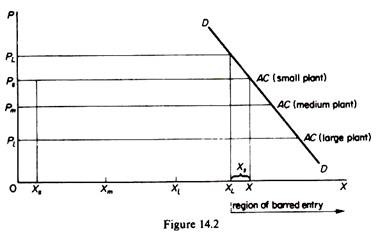

In figure 14.2 the market demand at the minimum acceptable price Ps of the smallest, least efficient, firm is X. The leader will set the limit price PL > Ps. The price PL corresponds to the level of output XL = X – Xs and is the equilibrium price because it satisfies the two necessary conditions: it is acceptable by all firms, and it deters entry, because if entry occurs the total output XL will be increased at the level XL + Xs = X and the price will fall to (just below) the minimum acceptable price of the entrant, that is, to a level just below Ps.

The PL is indirectly determined by the determination of the total output that the established firms will sell in the market. Given that in the long run price cannot fall below the cost of the least efficient firm, and that the entrant can enter only with the smallest least- efficient plant size, the leader can determine the output X at which all established firms use their plants up to capacity. He next determines the total quantity that the firms will sell in the industry XL so as to prevent entry.

XL is such that if the entrant comes into the market with the minimum viable size, Xs, the total post-entry output (XL + Xs) will just exceed X, and hence will drive price down to a level just below the AC of the entrant (= AC of the small least-efficient firms). Given XL, the limit price PL is determined from the market-demand curve DD. The entrant will be deterred from entering the market because (under the Sylos’s Postulate) he knows that if he enters he will cause the price to fall below his AC. Any output larger than XL is entry-preventing, while any output smaller than XL will not prevent entry.

It should be clear that in Sylos’s model all firms earn abnormal profits, which are increasing with plant size and there is an upper and a lower limit of the entry-preventing price: the equilibrium price cannot be higher than PL nor lower than Ps.

In Sylos’s model the determinants of the entry-preventing price are:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(1) The absolute size of the market X.

(2) The elasticity of market demand.

(3) The technology of the industry, which defines the available sizes of plant.

(4) The prices of factors of production, which, together with the technology, determine the total average cost of the firms.

The absolute market size:

There is a negative relationship between the absolute size of the market and the limit price. The larger the market size the lower the entry prevention price. If there is a dynamic increase in the demand, denoted by a shift to the right of the industry-demand curve, the effect on the price and the structure of the industry depends on the size and the rate of increase.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If the increase in demand is considerable and occurs rapidly, the existing firms, if they want to prevent entry, must lower the price (or set a lower price initially, in anticipation of the developments on the demand side) and build up additional capacity to meet the demand (or have adequate foresight so as to keep a continuous reserve capacity).

If the price is high and profits lucrative, and if the established firms cannot build up capacity fast enough to keep up with the rate of growth in demand, then entry from new firms or already established firms in other industries will take place. If we relax the restrictive assumption that the entrant will enter with the smallest optimal plant size, and accept that large firms from other industries manage to enter at a lower cost, some or all of the small firms will be eliminated, and price will fall.

Thus a rapid increase in the absolute market size will tend to reduce price and increase the average plant size in the industry, unless the existing firms can keep their shares constant by keeping continuously adequate reserve capacity. This policy, however, may be very costly. Thus in fast-expanding industries entry is almost certain to occur and price will be reduced.

If the growth of demand is slow, the existing firms will most probably be able to meet the increased demand by appropriate reserve capacity and gradual new investment, and the price will not be reduced unless new techniques with lower costs can be adopted for the larger scales of output to which the established firms are gradually led.

The elasticity of market demand:

The elasticity of market demand is also negatively related to the limit price. The more elastic the demand is, the lower the price that established firms can charge without attracting entry. If at the going price there is a considerable increase in the elasticity of demand (for price reductions), and if the firms are able to identify clearly this change in the elasticity of demand, the effects on price and on market structure are the same as in the case of a shift in the market demand.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The detection of changes in the elasticity is almost impossibly difficult in practice, and the established firms will most probably not count (and plan ahead) on such uncertain changes in e. Thus if e does in fact change substantially, new large firms (established elsewhere) will enter into the market, since the existing firms will not be able to cope with such change, and the price will fall.

The Technology and Technical Change:

The technology determines the minimum viable plant size. In any given ‘state of arts,’ the larger the minimum viable plant size, the higher will be the limit price. Thus there is a positive relation between the minimum viable plant and the premium included in the limit price.

If technology changes (technical progress) and benefits all plant sizes, costs will fall and price will decrease. However, if technical progress is such that only large firms have access to it, the limit price will not change. The large firms will have larger actual profits, but under the assumptions of Sylos’s model the price need not change. If technical progress is associated with product innovation (rather than process innovation) the price in the market will not normally be affected. One should expect an intensification of non-price competition as all firms in the industry will attempt to imitate the innovation.

Sylos seems to imply that technical progress is accessible only to the large firms who can afford large research and development departments. He argues that in the real world the large firms will not have any incentive to lower the price of their commodities despite the reduction in their costs. Under these conditions the large firms will realise higher profits and this will have serious implications for the distribution of income and employment. This argument is elaborated in the second part of Sylos’s book. However, we will not deal with these macro-aspects of Sylos’s theory.

The Prices of Factors of Production:

Changes in factor prices affect all the firms in the industry in the same way. Thus an increase in factor prices will lead to an increase in the costs and the limit price in the industry. Similarly a reduction in factor prices will lead to a decrease in the limit price.

Differentiated oligopoly:

Sylos extended his analysis to the case of differentiated oligopoly. Sylos argues that when the products are differentiated the entry-barriers will be stronger than in the case of homogeneous oligopoly due to marketing economies of scale. He seems to accept that advertising unit costs and possibly the cost of raw materials per unit of output are likely to fall as the scale of output increases. Hence the overall cost difference between the smaller and larger plants will be greater as compared to the homogeneous oligopoly case. Product differentiation, therefore, will reinforce the scale-barrier.

Sylos’s analysis of differentiated oligopoly lacks the rigour of his model of homogeneous oligopoly. He suggests, however, that he is primarily concerned with the implications of technological discontinuities for price and output, and that product differentiation is one of the main concerns of the ‘theoreticians of imperfect competition’ to whose analysis Sylos’s work is complementary.