In this article we will discus about:- 1. Importance of Land Reforms 2. Farm Size and Productivity 3. Tenancy Reforms, Agricultural Productivity and Efficiency.

Importance of Land Reforms:

After abolition of Zamindari system which involves several intermediaries between the State and the tenant or actual tiller of the soil, there are two types of land reforms that have important bearing on production and employment in agriculture. These are – (a) redistribution of land through imposition of ceilings on land holdings, and (b) reforms in the tenancy system. The purpose of reform of redistribution of land through imposition of ceilings on land holdings was to bring about equitable distribution of scarce agriculture land among poor rural households consisting of small and marginal farmers and landless agricultural labour.

The principle of equity is the guiding principle of redistribution of land through imposition of ceilings on land holdings. Besides, the creation of small farms through the redistribution of land also leads to the increase in productivity and employment in agriculture and thereby helps to solve the problems of poverty and unemployment in developing countries like India.

The tenancy reforms include the fixation of fair rent, guaranteeing security of tenure and conferment of ownership rights to the self-cultivating tenants and sharecroppers. The land reforms in India were emphasized in India’s Second Five Year Plan wherein it was stated that the objectives of these reforms are – ”firstly; to remove the impediments upon agricultural production as arise from the character of agrarian structure and, secondly, to create conditions for evolving as speedily as may be possible an agrarian economy with high levels of efficiency and productivity.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It follow from above that land reforms are important both from the social and economic viewpoints. From the social point of view redistribution of land and creation of small farms is important for promoting not only equity or distributive justice but also for increasing efficiency and productivity of agriculture. The rural poor constitute a significant segment of the population.

Giving them any assets must therefore help them to earn some income from the assets. Recent studies have found that more equitable distribution of wealth (including land) can promote efficiency. With more assets the poor are able to get more credit and better insurance coverage which induces them to make more investment. This leads to the rise in productivity of land. Reforms in the tenancy system would remove disincentives on the part of tenants to put in more labour and other inputs to increase output as well as to undertake long-term investment in land.

In what follows we will first discuss the relationship between farm size and agricultural productivity. The inverse relationship between farm size and productivity implies that land reforms could raise productivity by breaking less productive large farms into several more productive small farms. If productivity under sharecropping is lower than the owner-cultivated farms, then conferment of ownership rights to the sharecroppers will increase productivity and efficiency in agriculture.

Farm Size and Productivity:

The relationship between farm size and agricultural productivity per hectare has been a great controversial issue of the Indian agriculture as case for redistribution of land from large landowners to small farmers and landless agricultural labour depends on it. With the publication of Farm Management Studies in the mid-nineteen fifties and early 1960s it was found that there existed inverse relation between farm size and productivity of land, that is, productivity per hectare was higher on small farms as compared to the large farms.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This gave rise to the controversy about the proper explanation of this inverse or negative relation between the farm size and productivity or yield per hectare. Amartye Sen argued that small farms employ family labour and due to the existence of large-scale unemployment in the economy, the opportunity cost of labour for the small farms was zero and therefore they would apply labour to the point where marginal product of labour is zero and in this way small farm using family labour would maximise production.

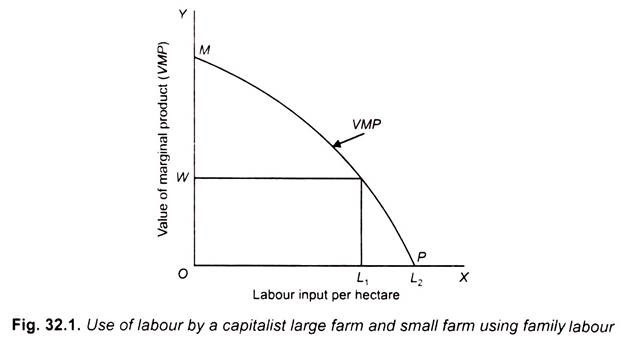

On the other hand, according to Sen, large farms generally employ hired labour and would use labour to the extent where value of marginal product of labour is equal to the market wage rate. This is illustrated in Fig. 32.1 where MP is the value of marginal product (VMP) of labour. Now, the small farms using family labour will apply OL2 amount of labour at which value of marginal product is zero and the total output is maximised to OMP which equals the whole area under the VMP curve up to L2. On the other hand, large farms using hired labour will apply labour equal to OL1 at which value of marginal product of labour (VMP) is equal to the market wage rate OW.

In this way the large farms will maximise their surplus or profit. It will thus be seen that large farms using hired labour will apply less labour as compared to small farms using family labour. As a result, according to Sen, with the given technology, productivity per hectare on small farms will be more as compared to the large farms using hired labour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Krishna Bhardwaj in her important study using Farm Management data of nineteen fifties found that the higher productivity per acre on small farms was due to higher cropping intensity on them as well as the cropping pattern with more valued crops being grown by small farms. A. M. Khusro attributed the higher productivity of small farms to the superior soil fertility of the small farms.

Ashok Rudra challenged the validity of the inverse relation between farm size and productivity and on the basis of empirical study asserted that there existed no such negative relationship between productivity and size of farm. However, Rudra related output per acre of gross cropped area with farm size and, therefore, his findings were criticized among others by Krishna Bhardwaj and Hanumanth Rao who pointed out that gross cropped area subsumed the effect of cropping intensity which was negatively correlated with farm size.

Thus, according to them, Rudra’s study did not disprove the inverse relation between productivity per hectare and the size of operational holding. G.R. Saini who made a comprehensive study of the relation between farm size and productivity per hectare using disaggregated farm management data of nineteen fifties of several districts of India concluded, “By and large inverse relation between farm size and productivity is a confirmed phenomenon in Indian agriculture and its statistically validity adequately established.”

Surprisingly, however, the negative relationship between farm size and productivity did not remain inverse for a long time when after 1965 the new high-yielding technology of using HYV seeds along with fertilizers came to be used in Indian agriculture. In the early years of green revolution in Indian agriculture the relationship between farm size and productivity got reversed and turned positive.

This is because in the early years of post-green revolution period, it was mainly big farmers having adequate resources to buy new inputs (HYV seeds, fertilizers, pesticides) adopted the new technology to a much large extent than the small farmers who lacked the resources to buy the new inputs. Thus the adoption of new high-yielding technology by large farmers in the early years of green revolution to a much greater extent more than offset the advantage of small farms applying larger human labour per hectare and having greater cropping intensity. From this it follows that it is not the farm size as such but other factors such as human labour, new technology inputs such as HYV, fertilizers that are responsible for the level of productivity of a farm.

As a matter of fact, the new high-yielding technology is size neutral. Therefore, after a time lag when adequate credit was made available to the small farmers by financial institutions to buy new technology inputs such as HYV, fertilizers, pesticides along with improved extension services, they also adopted the new high-yielding technology to almost the same extent, the inverse relationship between farm size and productivity again appeared.

Thus Hanumantha Rao writes. “In the early phase of green revolution, large farmers, owing to better access to capital resources stepped up yields per acre at a faster rate than small farmers. Because of this, in areas experiencing technological change the inverse relationship between farm size and for output per acre began to disappear. In course of time, however, the supply of institutional credit for the less developed regions and for small farmers improved significantly. As a result of this and also because of improved extension services the use of new seed-fertilizer technology among small farms caught up with that among large farms. And, because of the continued advantage of the small farms have in respect of cropping intensity, the inverse relationship between farm size and output per net cropped area has started reappearing. However, labour input continued to decline sharply with the increase in size of holding.”

Thus, the above view confirms our view that the farm size as such (that is, farm size net of other inputs) does not affect the agricultural productivity. To confirm this empirically the present author in his unpublished Ph.D. thesis submitted to the University of Delhi in 1982, instead of farm size as a single independent factor determining agricultural productivity per hectare estimated the following functions containing a number of relevant variables as independent factors that affect agricultural productivity. Note that our data belong to the early phase of post-green revolution period-

Log X = B0 + B1log FS + B2log CI + B4log Ht + B5Ig + B6log HL + B7D1

ADVERTISEMENTS:

where X denotes agricultural productivity per hectare, FS is farm size measured by net sown area (NSA) in hectares, HT high-yielding technology (that is, expenditure on HYV seeds + fertilizers + pesticides), HL is human labour, CI stands for cropping intensity (i.e GCA/NSA x 100). IG is expenditure on irrigation; D1 is tractor dummy that is estimated for Ferouzepur district of Punjab only.

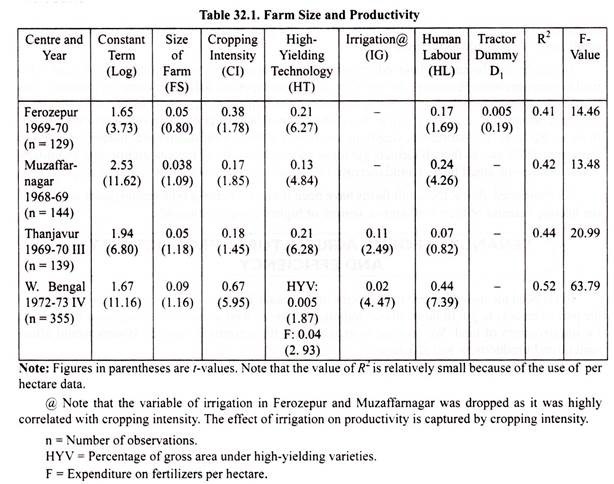

The above log-linear production function was estimated and the results obtained are given in Table 32.1.

The results obtained from the above function given in Table 32.1 indicate that partial elasticity of output per hectare with respect to size of farm is not found to be significant by conventional statistical standards in all the four centres. This clearly shows that size of the farm as such does not appear to have any impact on productivity. As will be seen from Table 32.1, it is other factors, namely, high-yielding technology, cropping intensity, irrigation and human labour that increase productivity. The coefficient of tractor dummy is quite insignificant showing that the use of tractors does not increase productivity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In case of West Bengal, the coefficients of ‘ara under HYV’ and expenditure on fertilizers (F) are very small though statistically quite significant. This is due to high correlation with cropping intensity, the coefficient of which captures some of their effects. Besides, data limitation did not permit us to combine the use of HYV and fertilizers (F) to find out their combined effect.

Thus in the conventional way of estimating the simple log-linear relationship between farm size and productivity, the coefficient of farm size subsumes some effect of other factors that determine productivity. In the mid-fifties when traditional technology was in use both on small and large farms; productivity on small farms was higher as compared to that on large farms because of the greater use of labour input per hectare as well as greater cropping intensity on the small farms. But in the post- green revolution period, the use of fertilizers and HYV and in some centres availability of irrigation (due to installation of tube-wells and pump-sets by large farmers) was greater on large farms which tended to offset the advantage of greater labour input and higher cropping intensity of small farms.

As a result, the negative relationship between farm size (gross of other factors) and productivity either weakened or no longer applied in the post-green revolution period. With regard to the effects of land redistribution on output and employment we must also note- (i) that differential access to credit facilities enjoyed by large farmers at present would cease to exist if the land is redistributed because in that case, there would be no big farmers, (ii) that the greater cropping intensity and labour use on small farms would tend to increase output.

Hence the conclusion that land redistribution would not only increase employment but would also tend to increase output because of the use of greater labour input and the higher cropping intensity. This would hold even if the output augmenting factors such as fertilizers, high-yielding varieties, irrigation are kept constant. Of course, if along with redistribution of land suitable institutional reforms are also made in the financial institutions supplying credit and in the administrative machinery distributing fertilizers, HYV etc. so that all farmers get these additional modern inputs in appropriate quantities, output per acre on small farms would increase further which in turn would further raise employment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The small farms have been found to increase both employment and output per hectare because of their well-known feature of higher cropping intensity.

Tenancy Reforms, Agricultural Productivity and Efficiency:

The reforms in the tenancy system would remove disincentives on the part of tenants to put in more labour and other inputs as well as undertake long-term investment for improvement of land. We propose to explain how the reforms in tenancy system would affect agricultural productivity and efficiency.

When a farmer gets land on rent, his production decisions will be determined to a great extent by the rent contracts made with the landowners.

In this connection two types of rental arrangements are noteworthy:

(i) Fixed Rent System:

Under this system a fixed amount whether in kind or cash is paid by the tenant to the landlord.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(ii) Share-Cropping Tenancy:

Under this system a certain share of the crops, generally 50%, is paid to the landlord.

Of the above two, crop-sharing tenancy has come in for heavy attack on account of its adverse effect on agricultural output and resource use efficiency. Under fixed rent tenancy the landlord regardless of the amount of output he produces, that is, after paying a fixed sum, the fixed-rent tenant would retain 100 per cent of extra output that he produces. As will be seen below, the fixed rent tenant, like the owner-cultivator, has the incentive to maximise surplus over cost and accordingly will put in more labour and other inputs.

In contrast, the share-cropper has to pay to the landlord 50% share of any extra output he produces he would have no incentive to put in labour which maximises overall surplus over cost but will employ labour and other inputs which maximises his share of surplus over cost. This is however subject to the condition that the labour supply or work effort supplied by the sharecropper cannot be monitored and controlled by the landlord.

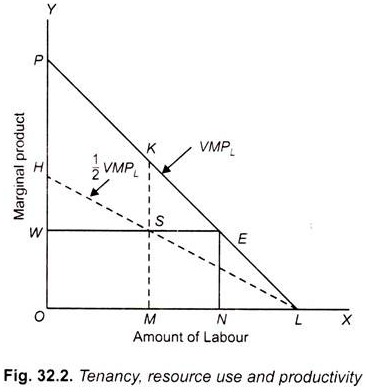

The decision of the sharecropper is illustrated in Fig. 32.2 where on the X-axis the amount of labour applied is measured and along the Y-axis marginal product of labour is measured. VMP measures the value of marginal product of labour and due to the operation of law of diminishing returns is stopping downwards. If 50% is the share of output that a sharecropper has to pay to the land owner, then marginal return to his labour will be half of the marginal product a labour.

Therefore, in Fig. 32.2 1/2 VMP curve represents marginal return to his labour. OW is the market wage rate of labour which represents opportunity cost to the sharecropper. While explaining the cost of labour for sharecroppers equal to market wage rate OW, Debraj Ray writes – “Labour is costly to the tenant. Labour does have other uses. For instance, part of labour may be hired by the tenant for a wage. Even if this is not the case, the tenant could work as a labourer on somebody else’s plot or might have some land of his own on which he wishes to devote part of his labour. ”

Now consider Fig. 32.2. A landowner who cultivates his land using hired labour will equate value of marginal product (VMP) of labour with market wage rate OW and apply ON amount of labour to maximise his surplus over cost (Note that labour cost is the only cost incurred by the landowner). With the use of ON amount of labour the total output is given by the area OPEN and the total wage cost is OWEN and therefore surplus earned by the landowner is given by the area WPE.

Now consider the case of a sharecropper who pays 50 percent (or one-half) of output to the landlord as rent. For him, as explained above, the marginal return of his labour is given by the curve HL which is ½ VMP at every extra unit of labour applied. Therefore, HL or ½VMP curve would be vertically halfway from the marginal product PL of labour. As explained above, for the sharecropper the opportunity unity cost of labour is also the market wage rate OW. However, in order to maximize his own return the sharecropper will equate his marginal return (i.e., ½ VMP) with the given market wage rate OW ½ by applying OM labour and thereby maximise his net total return (WHS). Note that total output produced by the share cropper is given by OPKM but he gives half of it to the landlord as rent.

It will be seen from Fig. 32.2 that share-cropper produces MKEN less output than the landlord using hired labour for cultivation of his land. It is therefore sad that because of the incentive problem share-cropping leads to inefficiency in use of labour as he undersupplies labour and therefore produces less output compared to owner cultivator using hired labour.

Tenant with a Fixed Rent Contract:

Now, how much labour will be applied and output produced by a tenant who pays a fixed sum to the landlord no matter how much output is produced by him? Since the tenant with a fixed rent contract after paying the fixed amount obtains the whole of extra output produced by him, he has the incentive to apply labour so much that maximises total economic surplus. As the alternative for the fixed rent tenants is to work on other farms at the market wage rate OW, he will apply labour to the extent at which value of marginal product (VMP) equals the wage rate as this maximises his surplus.

Thus labour applied and total output produced under fixed tenancy is the same (labour applied equal to ON and output produced equal to OPEN) as under owner- cultivator using hired labour. Thus, unlike share-cropping under fixed tenancy there is efficiency in resource use. To summarise, in the words of Prof. Debraj Ray, “the use of contracts other than a fixed rent contract, leads to the distortion of tenant’s input supply away from the efficient level. In particular it appears that- (i) sharecropping leads to the under-supply of the tenant’s inputs and (ii) rational landlord trying to maximise the earnings from land lease will always prefer a suitable fixed rent contract to any share contract”.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Empirical Evidence:

Some thought that the differences in productivity on self-cultivated and share-tenancy reforms were due to the heterogeneity of farmers in terms of ability and/or in terms of soil fertility. If the differences in productivity were due to differences in farmers ability or quality of soil, then the efficiency case for land reforms is weakened. However, empirical evidence proves this wrong. Empirical evidence shows that share-cropping tenancy reforms led to the improvement of productivity.

For example, Shaben found after controlling for land quality that the same farmer puts in less effort in plots of land that he cultivates as share-cropper compared to plots of land that he cultivates as owner cultivator. Similarly, an empirical study to test the effect of tenancy reforms on productivity by A.V. Banerjee, P.J. Gertler and M. Ghatak studied thoroughly the data from West Bengal after the tenancy reforms were implemented by the government of the Leftist parties, which was elected in 1977, found that tenancy reforms improved agricultural productivity under these reforms, which were called Operation Barga, under which registered tenants with the Department of Land Revenue would be entitled to permanent and inheritable tenure on the land they sharecropped as long as they paid the landlord 25 per cent of output as rent.

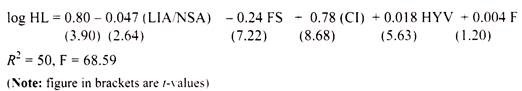

The present author in his Ph.D. dissertation submitted to Delhi university in 1982 econometrically tested the effect of sharecropping tenancy on employment and output per hectare using Farm Management Data of West Bengal covering six districts (24 Parganas (North), Nadia, Murshidabad, Hoogly, Burdwan and Birbhum) for the year 1972-73, that is, before the land reform of ‘Operation Bagra.’ The variable of share cropping intensity was measured as percentage of leased in area (LIA) to the net sown own (NSA), that is, LIA/NSA. The higher LIA/NSA, the greater will be the degree of share – cropping intensity.

Since farm size, the use of HYV and fertilizers, cropping intensity also affect employment and output, it is imperative to isolate their effects from the effect of share-cropping on farmer’s own labour employment.’ It is worth mentioning that though irrigation is a crucial factor in determining agricultural employment and output, but as it is highly correlated with cropping intensity, the use of HYV and fertilizers, its effect is subsumed by these other factors.

To test the impact of share-cropping on employment and output per hectare, the following two regression equations were estimated:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. log HL = β0 + β1 (LIA/NSA) + β2 FS + β3 log CI + β4 log HYV + β5 log F

2. log x = β0 + β1 log (LIA/NSA) + β2 log FS + β3 log CI + β4 log HYV + β5 log F.

Where, HL = employment (man-days) per hectare of net shown area

LIA/NSA = percentage of net sown area leased in and is a measure of share-cropping intensity

FS = farm size, that is, net shown area of the farm (in hectares)

HYV = area under HYV

FS = Expenditure on fertilizers per hectare

x = output per hectare

The following estimates of B coefficients of regression equation (1) with log HL as the dependent variable were obtained –

It will be seen from the above that the coefficient of share-cropping variable (i.e., LIA/NSA) is negative and statistically quite significant which shows share-cropper will use his labour input (HL) less as compared to the owner-cultivators, the effects of other employment determining factors having been isolated. Further note that the cropping intensity (CI), HYV and fertilizers have positive effect on employment per hectare. Cropping intensity has a very large effect on employment.

Effect of Share-Cropping on Productivity:

We now turn to show the impact of share-cropping tenancy on productivity per hectare in West Bengal (for the Year 1972-73) by estimating the equation 2 above with log x (log of output per hectare as the dependent variable).

The following estimates of β-coefficient were obtained:

It will be seen from the estimates that cropping intensity (CI), the use of high-yielding varieties of seeds (HYV) and fertilizers (F) have a positive effect on agricultural productivity per hectare. But the crop-sharing tenancy as measured by LIA/NSA has a negative effect on productivity per hectare and its coefficient is statistically significant. This shows sharecropping adversely affects agricultural productivity per hectare. Irrigation was not included in the final estimation of the regression as it was highly correlated with cropping intensity, the use of HYV and fertilizers and, therefore, its effect is subsumed in these other variables.

It is evident from the above that the reasoning advanced by Amartya Sen (1975) and R. A. Shaban that share-cropper uses less of its own labour and other inputs and therefore producers less output per hectare as compared it to the owner cultivator has proved to be correct in case of West Bengal where share-cropping tenancy predominantly prevailed before the land reforms of the leftist Government after 1977.

We may add to the reasonings why productivity under crop-share tenancy is lower. Share-croppers lack risk-bearing capacity and are also not able to get credit to finance its needs of required inputs, especially for the adoption of high-yielding technology if costs are not shared by the landlord. Besides, share tenants lack security of tenure and this may also leads to lower investment in the improvement of land. This may render their land of poor quality incapable of producing more.