The use of economic incentives to protect the environment is perhaps best known from the control of pollution. Many countries have adopted the “polluter pays principle” and require industries to pay a tax based on the amount of pollutant emitted.

This provides an incentive for industries to pollute less. More and more, those concerned with green rather than brown issues (conservation of bio diversity rather than control of pollution) are emphasizing the role of incentive measures as a conservation tool.

Recently, however, some nations have begun to experiment with economic incentive-based programmes. Incentive-based programs range from the very simple like refundable deposits on glass bottles to the extremely complex like issuing “permits to pollute” to factories and allowing the permits to be traded on the open market.

Refundable Deposits:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Current hazardous waste laws make it expensive to collect used motor oil, toxic chemicals, and certain auto bodies for recycling. As a result, illegal disposal is often the most profitable option. Illegal dumping can account for as much as 99 per cent of these wastes.

A report now under preparation by California futures presents a deposit- refund system on dangerous chemicals or their containers. An effective deposit system could make illegal disposal more expensive than safe disposal, eliminating the profit in toxic waste.

For example, Egypt uses some incentive-based measures. Glass bottles, for example, do have a return value in Egypt. As a result, glass bottles are seldom seen lying on the streets. This type of measure needs to be extended. Plastic bottles are not as easy to recycle as glass, but if the government enforced a deposit on them, pollution would decrease immensely.

Currently, mineral water bottles are strewn up and sown the Nile along tourist cruise ship path and in other tourist areas. If Egypt required a deposit, the money would ship operators to local profiteers, who could recoup the deposits and reduce pollution simultaneously. Other incentive-based strategies are less familiar than the deposit-refund scheme but can be equally effective.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Permits to Pollute:

Once a factory engages in its own gainful production affairs, it would have no incentive to decrease pollution further. By contrast, if the factory had to pay taxes for every unit of pollution it emitted, it would have an incentive to keep seeking new ways to cut pollution. Permits to pollute are another similar strategy.

The government decides on an acceptable level of pollution based on scientific and medical research. It issues a total number of permits that would achieve this level and distributes or sells them to polluters. Factories could them trade the permits between themselves, factories that could clean up easily would do so and sell their permits on the open market.

Tradable Pollution Permits (TPP) can be allocated in two ways:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Giving them away pro rata with existing emissions known as grandfathering.

2. Auctioning them to firms which enables them to trade these permits.

Firms with high Marginal Abatement Costs (MAC’S) serve as buyers and those with low MAC’S act as sellers.

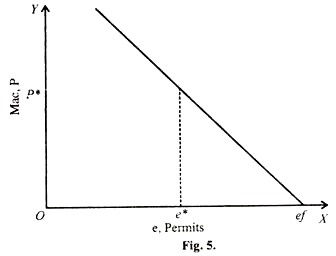

In the figure-5, the X-axis measures emissions, permits and the Y-axis measures price, MAC. Initial emission of the polluting firm is at of where the firm is making no attempt to control pollution.

TPP intervenes and fixes a price for permits at P*. Firm now chooses e* level of emissions as at any point below e* MAC> Price of permits. Therefore, the firm has an optimal response to a permit scheme, as it is cheaper to buy permits than to reduce emissions.

But if firm holds to pollute at any point > e* i.e. emit right of e* it will choose to sell P* it can get is > MAC. A firm with higher costs of controlling pollution will wish to hold more permits given a permit price of P*.

Therefore a firm compares its MAC schedule with the permit price to determine how many permits to hold. If price falls, more permits thereby lowering emissions. With any given increase or decrease in the supply or permits given a particular demand curve will decrease or increase the market-clearing price respectively.

i. Emissions Trading:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Emissions Trading Tradable permits have been applied to both air and water pollution control in the United States. A tradable permit establishes ownership of the right to pollute through a system of permits. Generally, a firm is allowed a certain number of permits, based on their existing waste generation.

Firmus may then trade or sell these permits in order to meet the pollution control requirement in the most cost-effective manner. Doing so can significantly increase the economic feasibility of clean manufacturing.

In studies conducted in the 1980s on three waterways—an 86-mile stretch of the Delaware Estuary, the lower Fox River in Wisconsin, and the upper Hudson River in New York—the mandated technology approach cost from 50 per cent to 200 per cent more than the least-cost approach.

ii. Pollution Fees:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Present law makes pollution free up to arbitrary limits set by the government, then suddenly creates a prohibitive cost that often turns out to be negotiable. Pollution fees are intended to make polluters pay for every unit they discharge. The objective: polluters should profit for every unit they reduce.

The concept could even be applied to the worst of polluters— internal combustion engines. Under one proposal, car registration fees would be set according to fuel economy or average emissions per mile for each model.

Another proposal, caller DRIVE+, would adjust sales taxes on cars to benefit high-mileage vehicles. A third would scrap today’s smog check systems, which misses the majority of offenders, and replace it with and electronic roadside monitoring system. This system would enable authorities to detect and fine the 10 per cent of vehicles that produce 50 per cent of the emissions.

When incentive-based programmes first began to appear, many environmentalists protested. They argued that if the government issued permits to pollute or levied a pollution tax, it was in effect sanctioning pollution. Yet in nations experimenting with incentive-based environmental laws, levels of pollution have dropped dramatically.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Of course, in some cases, it may turn out that simple rules and fines are the best policy, provided fines are set carefully. In all cases, the government should combine policies with other measures for example by using revenues from environmental fines to subsidies garbage disposal and recycling effort.

For example Egypt already employs several such environmentally sound strategies. Public transportation is subsidized in Egypt, decreasing private vehicle use and auto emissions levels.

Command and control policies sound nice, but are expensive to administer and are often fairly ineffective. Things like “permits to pollute,” by contrast, sound like concessions to polluters, by when well – designed, turn out to be much better for the environment.

Perhaps this is the good side of the newness of environmental law instead of a system of ineffective regulations. Learning from the policy blunders of other nations, one should pick the most effective policies and create a system of incentive-based environmental laws.

As for the burning garbage, new laws won’t put an end to them overnight. But the only way to improve the environment is to start putting out the fires, one at a time.

The market-based approach is becoming even more critical as the economy evolves into a system driven as much by knowledge as by physical resources. In this type of economy, driven by the wealth of new ideas and technologies, market-based policies may be preferable because they accelerate the application of knowledge to replace physical resources.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

By achieving environmental goals through the use of price signals and similar incentives, market-based laws operate systematically; they change the behaviour of businesses and individuals by changing the signals they receive in the economy.

Literally, they make the economy, and the organisations within it, smarter. This differs from most command-and-control laws, which operate programmatically, identifying specific behaviours, and attempting piecemeal reform by external force, without dealing with the overall system.

When they are administered effectively, market-based environmental policies tend to drive continuous improvements, not one-time gains. They lead to maximal pollution reductions, instead of stopping at politically acceptable levels.

They are designed to be much less expensive than mandates, often saving money rather than imposing higher costs. Finally, they are intended to root out waste systematically, empowering individuals and firms to apply creative solutions.

No economy can completely stop using physical resources. Still, the development and application of comprehensive market-based policies of the type discussed here, in concert with the on-going application of knowledge-driven technologies, have the potential to expand the resource productivity of the industrial economy by reducing the physical content and increasing the knowledge content of products and services.

Over time, this can reduce demand for raw materials and energy, thereby tending to reduce their price. Pressed far enough, efficiencies could lower the value of many raw materials and fuels toward zero, increasing the likelihood that they will be left in the ground, preserving the living ecosystem, and cultivating the emergence of a human economy characterised by increasing affluence and declining effluence.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The trouble isn’t in recognising this danger, or even in passing a law to try to prevent pollution. The trouble lies in passing a law that really does something to stop it.