Read this article to learn about the two possible solutions to over-estimation of GNP in an economy.

GNP is the money value of all the final goods and services produced in an economy during a given period; it has to be seen that intermediate goods are excluded as their inclusion may amount to double counting resulting in an over-estimation of the GNP.

There are two possible solutions to this problem:

(a) Take the sum of the values added at each stage, or

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(b) Take the values of the final products.

In the final goods method we exclude the value of all those goods and services which are of intermediate nature to the process of production (like wheat, flour, dough, etc.) in the preparation of bread, and include only final goods (and services) in the computation of GNP. The other method is the ‘value added approach, under which we estimate the increase in the value which each sector of the economy imparts during the production to the inputs which it gets from other sectors, and then we add up the value increases made by all different producing sectors of the economy.

The value added by a process to the products passing through it during a given period can be found by subtracting the value of the inputs from the value of the products leaving the process. The GNP estimates prepared in this way excludes the value of imports because their cost is automatically deducted from the value of the output of the industries using them, Again, to get NNP, depreciation has to be deducted from the sum of values added. Thus, GNP is the sum total of the values added by all the processes of production.

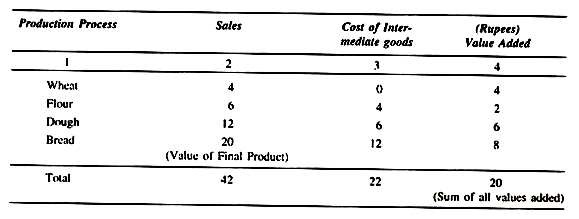

The concept of value added is most easily explained with the help of a simple example. Suppose, we imagine a simple economic system producing bread only. This system produces all the necessary inputs for the production of bread, but the final product that it produces is bread atone. We assume, there are mainly four parts to the production process, first, wheat is produced, then flour, then dough, and finally bread as shown in the following table.

In this table, we find that wheat is produced and sold to the Hour maker for rupees four. Since there is no production prior to wheat, the wheat producer added value of Rs. 4 to economy’s output. The value added by the wheat producer is Rs. 4. The Hour maker further sells the flour to the dough maker for Rs. 6. The flour maker paid Rs. 4 for wheat (input) and sold the Hour (output) to dough maker for Rs. 6. The value added by the flour maker, therefore, is Rs. 2.

When the dough maker finishes his work with the Hour, i.e., he mixes flour with water and makes it wet), he sells the product (wet flour with water called dough) to the bread maker for Rs. 12; the value added by the dough maker is Rs. 6. The bread maker works with the dough and prepares bread worth Rs. 20, thereby adding a value of Rs. 8 to the product. Thus total sales is Rs. 42 but this includes the value of many intermediate products and thereby represents more than final product (bread) alone. If we subtract from Rs. 42 the cost of intermediate goods (Rs. 22 as shown in column 3), we get the value of final goods, i.e., bread worth Rs. 20. In our example, Rs. 20 is the sales of bread.

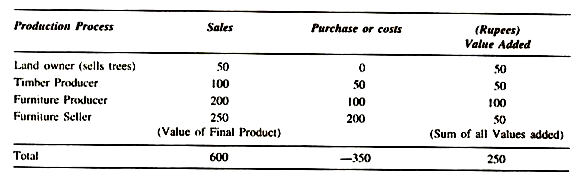

Thus, we find that the sum of all the values added (Rs. 20 in column 4) is equal to the value of final output (i.e., bread worth Rs. 20). This is obtained by adding the value of all the final output (i.e., sum total of values added by the wheat producer 4, plus flour maker 2, plus the dough maker 6, and the bread maker 8, we get 20). It is the final value of goods and services. In order to avoid the problem of double counting, value added method must be employed. Moreover, this shows that both the methods—value added as well as final goods method give us the same total as is shown by the table given on the top and the table given below.

It is, therefore, clear that logically it is immaterial whether the ‘value added method’ or the ‘final product method’ is employed in the computation of GNP because both lead to the same results and both have its merits and limitations. While the former takes into consideration the flow of output pass each process: the final products’ method counts the quantity of commodities which are delivered at the end of a given period, with suitable adjustments for the goods still in transit at the beginning and at the end of the period. The ‘value added’ method is in line with normal business accounting procedures because every firm records the value of its output and the value of materials used.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The ‘final products’ method is beset with a number of difficulties in that it requires a division of actual output in consumer’s goods and producer’s goods. In certain cases it becomes difficult to distinguish between a consumer good or a producer good, for example, a car is a consumer good and may also be used for business purpose and becomes producer goods. Under such conditions, it becomes difficult to say what part of it is to be treated as final or consumer good?

The value added method which enables us to measure the GNP by adding up the differences between the value of material inputs and outputs at each of production, is useful because it provides a method of checking the correctness of GNP estimates and also because it enables us to get information about the contribution of each production sector of the economy to the value of GNP. Calculation of the value added by government activity occasions difficulties, as government services are not available at market prices like defence, law and order, health and education etc.

Their values are measured only in terms of their cost, it is assumed that the cost of provision of such services represents the value which the society attaches to these services. Another case is of self-occupied house, though no rent is paid yet the value of the services can be calculated in money terms by assuming it to be equal to the rent paid by non-owning tenants. The problem that arises in this connection is, why not count on a similar basis the input values of services rendered by other things like cars, radios, television sets. This is, however, not done because of the apparent difficulties involved in assessing imputed values of different things.