Globalisation and India Economy!

Effect on Economic Growth:

The chief argument for globalisation and liberalisation was that they would lead to higher economic growth.

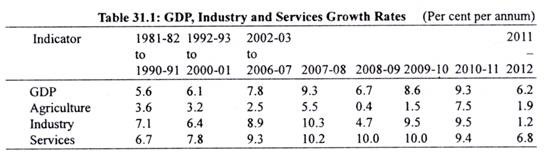

As a result of balance of payments crisis in 1991, growth in GDP which collapsed to 13 per cent in 1991 -92 gained momentum thereafter in the next 5 years period (1992-2001), the annual average growth rate in GDP achieved was 6.1 per cent.

However, in the 10th plan period as a whole (2002-07), average annual growth achieved had been 7.8 per cent. Besides, in the last three years of the 10th plan (2005-06, 2006-07 and 2007-08) growth rate in GDP rose to 9.5 and 9.6 and 9.3 per cent respectively. Thus, it was claimed that policy of liberalisation and globalisation has accelerated economic growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, under the impact of crisis of 2008-09 GDP growth rate fell to 6.7 per cent in 2008-09. It was because of fiscal stimulus provided by the government and expansionary monetary policy of RBI that economic growth could be revived to 8.6 per cent in 2009-10 and 9.3 per cent in 2010-11. However, due to adverse global factors such as slowdown in US economic growth and recession in European countries and Eurozone crisis affected our export growth in several months. As a result our economic growth was badly affected.

Growth rate in 2011-12 fell to 6.2 per cent and in 2012-13 to 5 per cent – lowest in a decade. Volatility of capital flows added to uncertainty. In 2013-14, growth rate is also expected to be around 5 per cent. It is thus evident that globalisation could not ensure sustained rate of higher economic growth. In 2013-14 Indian economy is said to be in crisis due to operation of mainly global factors.

Impact on Foreign Trade and Balance of Payments:

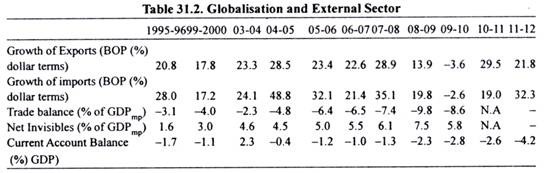

The effect of trade liberalisation and globalisation on foreign trade and balance of payments has been favourable. Export growth zoomed to 20 per cent in 1993-94, 18.4 per cent in 1994-95, and to 20.8 per cent in 1995-96. Growth of exports in recent years has also been quite impressive. Growth in exports in 2003-04, 2004-05 and 2005-06 was 23.3% 28.5% and 23.4% respectively (See Table 31.2). In 2006-07 and 2007-08, the growth in exports 22.6 and 28.9 per cent respectively.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Though imports also grew but due to robust growth in invisibles, current account deficit Table 31.2. remained below 2 per cent of GDP upto the year 2007-08 as compared to 1990-91 when this deficit was over 3.1 per cent of GDP. In three years period (2001 to 2004) current account balance turned into surplus. Along with surpluses on capital account this resulted in large increase in foreign exchange reserves.

As will be seen from Table 31.2 from 2005-06, 2006-07 and 2007-08 due to good growth in exports in these three years, current account deficit was less than 2 per cent of GDP which was easily financed by capital flows into the Indian economy. Thus the fears that liberalisation of imports by reducing tariffs and removing quantitative restrictions would open the flood- gates for massive imports which would not only worsen India’s balance of payments but would also kill domestic industries and slow down industrial growth have not come true.

In fact globalisation, according to this view, not only helped in the acceleration of industrial growth but also in improvement of balance of payments position. Liberalisation of trade and removing restrictions on foreign investment have led to increase in investment inflows from abroad which have helped the growth process.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, globalisation has not been without disadvantages and risks. Foreign capital flows by FIIs are highly volatile. When they come they lead to appreciation of rupee which discourages exports by making them costlier and encourages imports by making them cheaper.

However, when capital outflows by FIIs occur as has been the case since the last week of May, 2013 to end of August, 2013 due to the announcement by the governor of US federal Reserve that it would soon start unwinding quantitative easing (QE) policy because of the signs of revival of the US economy.

The capital-outflows by FIIs in months (June, July and Aug. 2013) led to the sharp depreciation of rupee and crash in India’s stock market. These capital outflows also make it difficult to finance current account deficit (CAD) which have adversely affected the sentiments of foreign investors.

Impact on Poverty:

Advocates of globalisation and trade liberalisation claimed that it would ensure greater reduction in poverty and unemployment in developing countries through acceleration of economic growth. The issue of reduction in poverty has been a highly controversial issue. Due to changes in methodology for measuring poverty in various rounds of NSS, it could not be said to what extent poverty declined in the post-reform period on account of the policies of liberalisation, privatization and globalisation.

However, NSS Survey 2004-05 made corrections in the data so as to be comparable with the 1993-94 survey data of poverty ratio. On the basis of uniform recall period (URP) the percentage of population in all India below the poverty line fell from 36 per cent in 1993-94 to 27.8 per cent in 2004-05 which amounts to 0.74 per cent annual reduction in poverty ratio in this post- reform period.

This is much less than rate of reduction in poverty rate in the pre-reform period when percentage of population below the poverty line declined from 51.3 per cent in 1977-78 to 38.9 per cent in 1987-88 which works out to be 1.2 per cent annual fall in poverty ratio.

However, an expert committee headed by Late Prof. Suresh Tendulkar suggested moving away from taking the calorie intake as defining parameter for poverty line to make a more comprehensive method of using per capita expenditure data on basic needs such as food, clothing, housing and services such as health and education.

Using this criteria for measuring poverty even from the data collected by NSSO for the year 2004-05, it was estimated that for all India 37.2 per cent of population lived below the poverty line. Further, on the basis of special NSSO survey conducted in 2011-12 and using Tendulkar Committee methodology, it has been estimated by the Planning Commission that in 2011-12, 21.9 per cent of India s population lived below the poverty line, that is, a decline by 15.3 per cent points in poverty in seven years between 2004-05 and 2011-12. In absolute numbers, the number of poor people declined from 407 million in 2004-05 to 269 million in 2011-12, that is, 138 million persons were lifted out of poverty line.

This was attributed to higher average rate of economic growth over 8 per cent per annum achieved during this period which was claimed by the government was due to the policy of liberalisation and globalisation pursued. This proved to be a highly controversial issue as critics pointed out that the estimates of poverty for the year 2011 -12 was very low because of a low poor line, a daily expenditure of Rs. 27.2 per capita for rural areas and Rs. 33.3 per capita for urban area.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It was said one could not survive on such a low expenditure. Some critics went to the extent of saying that such lower expenditure as a norm for poverty was a cruel job on the poor. In 2009-10, even Supreme Court of India rejected these poverty norms as too low for the people to survive. Therefore, under the pressure the government decided to appoint a new Committee headed by Dr. C. Rangarajan to suggest an alternative methodology for measuring poverty in India.

Further, in our view, reduction in poverty is not necessarily due to higher rate of economic growth which has been achieved by the use of highly capital-intensive technology generating little employment opportunities in the organised sector as will be seen later.

Of course, under the export-oriented trade policy under economic reforms with globalisation as its important feature a good number of employment opportunities has been generated in the export sector. However, liberalisation of imports under the policy of globalisation has tended to displace labour in many industries. However, whether, there has been a net increase in employment under the policy of liberalisation and globalisation is difficult to say.

Impact on Employment:

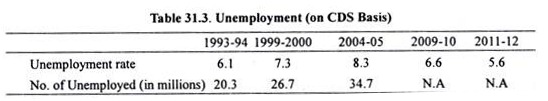

It is generally alleged that liberalisation and globalisation had adverse effect on growth of employment. All the three unemployment rates, namely, unusual status, weekly status and daily status, based on National Sample Survey, increased during the period 1993-94 to 2004-05 whereas they had declined earlier.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As will be seen from Table 31.3 that on the basis of current daily status (CDS) (i.e. unemployment on an average in the reference week) the rate of unemployment which was 6.1 per cent in 1993-94, rose to 7.3 per cent in 1999-2000 and further to 8.3 per cent in 2004-05. With this the number of unemployed which was 20 million in 1993-94 went up to 26.7 million in 1999-2000 and further to 34.7 million in 2004-05.

It may be noted that the growth of employment, according to National Sample Surveys, in the post-reform period from 1999-2000 to 2004-05 increased by 2.62 per cent annum as against 1.25 per cent in 1993-94 to 1999-2000. But all this growth of employment was in the un-organised and informal sector. In fact, as can seen from Table 31.4, the rate of growth of employment in the organised sector in the post-reform period 1994-2008 has been found to be only 0.05 per cent per annum whereas during the pre-reform period (1983-94) employment grew at 1.2 per cent per annum.

It will be noticed from Table 31.4 that in this post-reform period (1994-2008) there has been negative employment growth in the public sector, employment in the organised private sector showed some acceleration in employment growth from 0.44 per cent per annum during 1983-94 to 1.75 per cent per annum during 1994-2008.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, since the labour force grew at a higher rate of 2.84 per cent per annum than the growth in employment during this period the unemployment rate on current daily status (CDS) basis increased from 7.3 per cent in 1999-2000 to 8.3 per cent in 2004-05. However, in NSS surveys for the years 2009-10 and 2011-12 unemployment on current daily status (CDS) basis fell to 6.6 per cent and 5.6 per cent of labour force respectively.

But, according to our view this is due to the starting of Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGA) rather than the result of growth in the organised sector. However, employment created under MGNREGS is quite unproductive. Though wages are paid to the workers for the number of days employed but no durable assets are built by them.

Therefore, employment generated under the scheme is not sustainable. Further, it may be noted that though man-days of employment generated under the scheme have resulted in the declined in daily status unemployment in 2009-10 and 2011-12, there is no any increase in productive employment.

For the increase in unemployment in the formal sector since 1993-94, the policies of liberalisation and globalisation adopted since 1991 are often blamed. First, under this policy the import tariffs have been substantially reduced making imports cheaper. Deprived of protection many Indian small-scale industries could not compete with the imported products.

As a result, many small scale industries closed down rendering many workers unemployed. Many large-scale industries undertook modernisation of their plants using updated capital-intensive technology in order to compete with the cheap imported products and also to export more in foreign competitive markets. This did not help in the generation of a large number of new employment opportunities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In fact, even some large-scale corporate firms cut down jobs. That there has been jobless growth is revealed by 68th round of special employment and unemployment survey, 2011-12. This latest 68th NSSO survey reveals that the percentage of employed persons to the total population declined in 2011-12.

According to this, on the basis of usual principal and subsidiary status approach the proportion of population gainfully employed for better part of the year fell from 36.5 per cent of population in 2009-10 to 35.4 per cent in 2011-12 despite GDP growth of 8.6% in 2009-10, 9.3% in 2010-11 and 6.2 per cent in 2011-12. Though in percentage terms fall in employment appears to be small, in absolute numbers it will amount to several lakhs. As a result, usual principal and subsidiary status unemployment rose from 2.5 per cent in 2009-10 to 2.7% in 2011-12.

Strangely enough, some prominent economists are arguing for labour reforms under which the large firms are permitted to hire and fire workers feely. They argue that the firms are reluctant to hire and employ more labour because under the present labour laws, it is difficult for them to retrench them. Likewise, they argue that foreign direct investment is not coming to India in sufficient amount because of inflexible labour legislation.

They point out once labour reforms are undertaken, adequate employment opportunities will be created. However, in our view, this is a very simplistic view because growth of employment primarily depends on the rate of investment and the nature of technology used in the manufacturing industries and other sectors of the economy. If preference for use of capital-intensive technology to achieve higher productivity of labour, as has been the case so far, remains unchanged, adequate growth in employment will not take place.

This will lead to the increase in unemployment. Therefore, we cannot rely on market forces to generate enough employment opportunities. Conscious efforts have therefore to be made to promote labour-intensive techniques to take care of the presently about 37 million unemployed workers on current daily status basis found in 2007-08.

Similarly, increase in unemployment is due to the increase in capital intensity in production in agriculture, lack of investment in agriculture, non-implementation of land reforms, rapid growth in labour force. Plan after plan has been paying lip service to increasing labour-intensity of production to promote employment growth but policies to ensure this have not been implemented.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Exports, Imports and Employment:

In fact the expansion in exports following globalisation of the Indian economy has led to a large expansion in employment in the export sector. One of the objectives of foreign trade policy has been to make it an instrument of employment generation. In 2004-05 against exports of US $ 80 billion total employment growth in the export sector was 16 million (9 million direct and 7 million indirect).

In 2004-05, in the export sector the maximum employment created was in agricultural products (6.2 million) followed by mineral products (1.7 million), textiles and textile articles (1.7 million) and prepared foodstuffs and beverages etc. (1.6 million). However, while exports has recorded robust growth in recent years, the corresponding growth of labour-intensive goods has slowed down. We thus see that export promotion under globalisation has promoted employment growth rather than reducing it.

However, it is claimed by many that liberalisation of imports as a result of globalisation of the Indian economy has adversely affected employment situation in the Indian economy. This is because small and medium enterprises which have large employment potential could not compete with the cheap imports from the developed countries and China. This led to closure of several small and medium enterprises resulting in loss of employment opportunities.

Thus whereas growth of exports has tended to increase employment opportunities, cheap imports from abroad have tended to reduce them. Which effect on employment has been stronger is anybody’s guess. However, as seen from Table 31.4, in the organised sector there has been net 0.05 per cent growth in employment per annum in the organised sector (in the public and private sectors taken together) during 1994-2008.

Foreign Capital Inflows: FDI and Portfolio Investment:

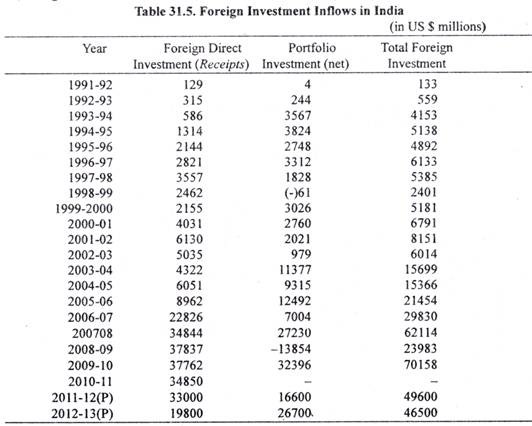

Policies of liberalisation of private capital inflows have led to the increase in foreign investment flows in the country both in terms of direct investment (FDI) and portfolio investment. Profile of foreign investment flows is given in Table 31.5. It will be seen from this table that annual total investment inflows which were about US $ 4.15 billion in 1993-94 rose to about 6.1 billion US dollars in 1996-97 and varied a lot after that but reached US $ 15.7 billion in 2003-04 and a record figure of US $ 29 billion in 2006-07. In the year 1998-99, there was negative portfolio investment inflows’ following the East Asian currency crisis in 1997-98.

In the year 2006-07 and 2007-08 foreign investment inflows in India had been quite substantial indicating the rising confidence of international investors in the Indian economy. In the year 2006- 07, foreign direct investment (FDI) 22.8 billion US $ and portfolio investment of 7 billion US dollars came into India. In 2007-08 foreign direct investment (FDI) of 34.8 billion US $ was made in India.

In fact India became a favorite destination for foreign direct investment. Besides, in the year 2007-08, about 27.2 billion US dollars were brought into India by FIIs for purchase of equity shares (i.e. portfolio investment). However, in 2008-09 following the sub-prime housing loans provided by American banks, financial crisis occurred in American and Western Europe which created liquidity crunch in their economies and redemption pressure on securities held by FIIs increased very much.

To fulfill the liquidity needs of their parent countries FIIs sold shares in the Indian stock market on a large scale and repatriated dollars. The large-scale sale of shares by FIIs and capital outflows not only caused crash in Indian stock market but also resulted in large depreciation of Indian rupee. Besides, the world financial crisis caused global meltdown which affected capital inflows into India through FDI.

However, there was reversal of portfolio capital flows in 2009-10. In 2009-10, India attracted foreign direct investment (FDI) of $ 37.7 billion and portfolio investment of $32.3 billion in 2009-10 and therefore total foreign investment of$ 70.1 billion in 2009-10. Foreign investment in inflows further declined in 2011-12 and 2012-13.

Effect on Foreign Exchange Reserves:

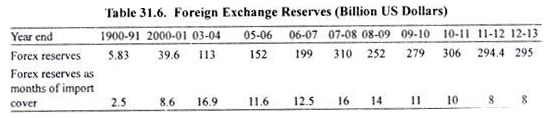

An important beneficial effect of the globalisation of the Indian economy has been that its foreign exchange reserves have been substantially increased. In Dec. 2003, our foreign exchange reserves crossed 100 billion US dollars and increased to 309.7 billion US dollars on February 2008. In 1991 we faced an acute foreign exchange crisis arising from continued deficits in balance of payments for several years. It is this crisis that compelled us to shift to the policy of liberalisation and globalisation.

At the end of March 1991 we had forex reserves of only about 6 billion US dollars which were sufficient to cover only 2.5 months of imports. At the end-March 2007-8 foreign exchange reserves of nearly 310 billion US dollars were adequate enough to cover imports of 16 months.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, during 2008-09 there was decline in foreign exchange reserves due to net capital outflows. At end-March 2009 foreign exchange reserves declined to 252 billion US dollars, but there was reversal of capital flows in 2009-10. As a result due to large capital inflows into the Indian economy the foreign exchange reserves rose to $279 billion in end-March 2010 and stood at around $306 billion at end-March 2011.

This huge accumulation of foreign exchange reserves has been possible because of the policy of liberalisation of foreign investment. The major contributor to dollar inflows in the Indian economy was Foreign Institutional Investors (FII) who invested in the Indian equity and debt markets. In the year 2003-04 alone capital inflows of 11.4 billion US dollars were brought by FIIs alone who invested in the Indian equity and debt markets. In the year 2007-08 appreciation of rupee caused large inflow of portfolio capital by FIIs resulting in increase in foreign exchange reserves to $310 billion in end-March 2008.

Quite a good part of foreign exchange inflows has also been due to NRI deposits. NRI brought their money to India in order to take advantage of the interest rate differentials between India and the US. A big chunk of these reserves was also due to external commercial borrowings (ECB) by Indian corporate firms. Capital inflows through foreign direct investment (FDI) also gained momentum in 2006-07, 2007-08 and 2008-09.

What are the reasons for a flood of inflows of foreign exchange in these years? Booming stock market of India, a robust growth of the order of over 9 per cent in the three years 2005-06, 2006-07 and 2007-08 and expectations of Indian corporate doing well and a high rate of return on investment in India were the important reasons for large inflows of foreign exchange reserves in these years.

An important thing to note about the accumulation of foreign exchange reserves has been that much of them had not occurred on account of foreign trade that is, exports and imports of goods and services. With the exception of three years (2001-02, 2002-03 and 2003-04) there has been a continued deficit in balance of payments on current account. However, a good thing about these reserves is that most of the increase in foreign exchange reserves were of non-debt variety and had not added to our external debt.

In fact, we pre-paid a part of costly external debt by using some foreign exchange reserves. The large foreign exchange reserves provided India a sense of security against any contingencies in future and permit us to take economic policy decisions independently without any preconditions by IMF and World Bank. In fact during 2008-09 when due to global financial crisis there were capital outflows on a large scale from India $20 billion of foreign exchange were withdrawn from our foreign exchange reserves to finance current account deficit.

This global financial crisis also caused a drastic depreciation of the Indian rupee. The rupee which had appreciated to Rs. 39.4 to a dollar in Oct. 2008 fell to Rs. 45 in July 2008 and to Rs. 49.30 to a dollar on in Oct, 2008 and further to around Rs. 50 in Nov. 2008. This depreciation in value of rupee made our imports including crude oil costlier which adversely affected our balance of payments in 2008-09.

Therefore, to finance current account deficit we had to draw upon our foreign exchange reserves equal to $ 57.7 billion in 2008-09. Therefore, our foreign exchange reserves fell from $ 310 billion in 2007-08 to $ 252 billion in 2008-09 (end-March).

During 2009-10 and 2010- 11 there was net capital inflows and as a result our foreign exchange reserves increased to $ 279 billion in 2009-10 and to $ 304.8 billion in 2010-11. Again in 2011-12, our current account deficit (CAD) was very large and capital inflows were insufficient to finance it fully. Therefore we had to withdraw $ 10.4 billion from our foreign exchange reserves.