In this essay we will discuss about Unemployment in India. After reading this essay you will learn about: 1. Meaning of Unemployment in India 2. Nature of Unemployment Problem in India 3. Extent 4. Causes 5. Remedial Measures 6. Characteristics 7. Employment Policy and Schemes 8. Growth of Employment and Others.

Unemployment in India Content:

- Meaning of Unemployment in India

- Nature of Unemployment Problem in India

- Extent of Unemployment

- Causes of Unemployment Problem in India

- Remedial Measures to Solve Unemployment Problem in India

- Characteristics of Employment Problem Followed in India – Its Critical Evaluation

- Employment Policy and Schemes in India

- Growth of Employment in India in Recent Years

- Is the New Economic Policy promoting Jobless Growth ?

- Global Economic Recession and its Impact on Unemployment Problem in India

Essay # 1. Meaning of Unemployment in India:

Unemployment is a common economic malady faced by each and every country of the world, irrespective of their economic system and the level of development achieved. But the nature of unemployment prevailing in underdeveloped or developing countries sharply differs to that of developed countries of the world.

While the developed countries are facing unemployment, mostly of Keynesian involuntary and frictional types but the underdeveloped or developing countries like India are facing structural unemployment arising from high rate of growth of population and slow economic growth.

Structural unemployment may be open or disguised type. But the most serious type of unemployment from which those undeveloped countries like India are suffering includes its huge underemployment or disguised unemployment in the rural sector.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Unemployment is a serious problem. It indicates a situation where the total number of job vacancies is much less than the total number of job seekers in the country. It is a kind of situation where the unemployed persons do not find any meaningful or gainful job in-spite of having willingness and capacity to work. Thus unemployment leads to a huge wastage of manpower resources.

India is one of those ill-fated underdeveloped countries which is suffering from a huge unemployment problem. But the unemployment problem in India is not the result of deficiency of effective demand in Keynesian term but a product of shortage of capital equipment’s and other complementary resources accompanied by high rate of growth of population.

Essay # 2. Nature of Unemployment Problem in India:

Present unemployment problem in India is mostly structural in nature.

Unemployment problem of the country can now be broadly classified into:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) Rural unemployment and

(b) Urban unemployment.

(a) Rural Unemployment:

In India the incidence of unemployment is more pronounced in the rural areas.

Rural unemployment is again of two types:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) Seasonal unemployment and

(ii) Disguised or perennial unemployment.

(i) Seasonal Unemployment:

Agriculture, though a principal occupation in the rural areas of the country, is seasonal in nature. It cannot provide work to the rural population of the country throughout the year. In the absence of multiple cropping system and subsidiary occupation in the rural areas, a large number of rural population has to sit idle 5 to 7-months in a year.

Seasonal Unemployment is also prevalent in some agro- based industries viz., Tea Industry, Jute Mills, Sugar Mills, Oil Pressing Mills, Paddy Husking Mills etc.

(ii) Disguised or Perennial Unemployment:

Indian agriculture is also suffering from disguised or perennial unemployment due to excessive pressure of population. In disguised unemployment apparently it seems that everyone is employed but in reality sufficient full time work is not available for all.

In India, about 72 per cent of the working population is engaged in agriculture and allied activities. In 1951 more than 100 million persons were engaged in the agricultural and allied activities whereas in 1991 about 160 million persons are found engaged in the same sector resulting in as many as 60 million surplus population who are left with virtually no work in agriculture and allied activities.

(b) Urban Unemployment:

Urban unemployment has two aspects:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) Industrial unemployment and

(ii) Educated or middle class unemployment.

(i) Industrial Unemployment:

In the urban areas of the country, industrial unemployment is gradually becoming acute. With the increase in the size of urban population and with the exodus of population in large number from rural to the urban industrial areas to seek employment, industrialization because of slow growth could not provide sufficient employment opportunities to the growing number of urban population.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus the rate of growth of employment in the industrial sector could not keep pace with the growth of urban industrial workers leading to a huge industrial unemployment in the country.

(ii) Educated or middle-class Unemployment:

Another distinct type of unemployment which is mostly common in almost all the urban areas of the country is known as educated unemployment. This problem is very much acute among the middle class people. With rapid expansion of general education in the country the number of out-turn of educated people is increasing day by day.

But due to slow growth of technical and vocational educational facilities, a huge number of manpower is unnecessarily diverted towards general education leading to a peculiar educated unemployment problem in the country. The total number of educated unemployment increased from 5.9 lakh in 1962 to 230.50 lakh in 1994.

Essay # 3. Extent of Unemployment:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In view of the growing problem of unemployment and under-employment prevailing in the country it is very difficult to make an estimate of the total number of unemployment in a country like India. As per the statement of the then Labour and Employment Minister in the Parliament, there was about 35 million unemployed person’s in-spite of 42.5 million new jobs created during 1951 and 1969.

Various agencies like Planning Commission, CSO, NSS etc. could not provide any dependable estimate about the magnitude of unemployment in India. As per the estimates of unemployment made in the Five Year Plan the backlog of unemployment which was 5.3 million at the end of First Plan gradually increased to 7.1 million, 9.6 million and then to 23 million at the end of Second, Third and Three Annual Plans respectively.

The number of unemployed as percentage of total labour force which was 2.9 per cent at the end of the First Plan gradually increased to 9.6 per cent at the end of Annual Plans in 1969.

The Committee of Experts on Unemployment under the Chairmanship of Mr. B. Bhagawati observed in its report (1973) that total number of unemployed in 1971 was 18.7 million out of which 16.1 million unemployed were in rural areas and the rest 2.6 million existed in urban areas. Moreover, unemployment as percentage of total labour force was to the extent of 10.9 per cent in 1971 for the whole country.

As per the Employment data, the number of registered job seekers in India rose from 18.33 lakh in 1961 to 165.8 lakh in 1981 and then to 370.0 lakh at the end of March 1994. Total number of educated job seekers has also increased from 5.90 lakh in 1961 to 230.0 lakh in the end of March 1994, which constituted nearly 62 per cent of the total job seekers of the country.

At the end of January 1996, total number of registered job seekers in India was 368.9 lakh. As on 1st April, 1997, total number of unemployed persons in India was 7.5 million. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) report World Employment 1995 observed that 22 per cent of all male workers in India are underemployed or unemployed and the figure is rising.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The employment in the modern sector in India grew only by 1,6 per cent per annum in 1980s, Underemployment in the rural areas also remained high.

The National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO) developed three concepts of unemployment since 1972-73.

These were:

(i) Usual Status Unemployment,

(ii) Weekly Status Unemployment and

(iii) Daily Status Unemployment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The magnitude to usual status unemployment (chronic unemployment) rose from 1.4 million in 1961 to 7.1 million in 1978.

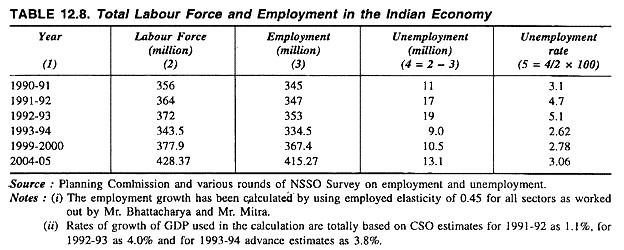

The Planning Commission’s estimates of usual unemployment revealed that the usual status unemployment at the age-group 5+ increased from 12.02 million in 1980 to 13.89 million in March, 1985. The total employment at the beginning of 1992-93 was estimated to be 301.7 million on a “weekly status” basis, and the labour force was estimated to be 319 million.

Again as per the NSS tentative estimates of unemployment for April 1990, the usual status and daily status unemployment were 3.77 per cent and 6.09 per cent respectively of the total work force in 1987-88. By adjusting these estimates, Arun Ghosh estimated the backlog of unemployment in April 1990 as—13 million of usual status and 20 million of daily status.

At the end of each Five Year Plan, the backlog of unemployment in India has been increasing as the volume of employment generated cannot match this additional number of labour included in work force. As per document of the Sixth Plan (1980-85), total number of unemployed was 20.7 million in 1980 which represents 7.74 per cent of the total labour force.

Ninth Plan (1997-2002) estimated the total backlog of unemployment as 36.8 million in 1996. Thus a huge portion of our national resources has been constantly used for the generation of employment opportunities so as to clear the backlog of unemployment arising from rapidly rising population.

By looking at a different angle, it is found that India’s population presently stands at 104 crore and increasing by nearly 1.6 crore per year. It is generally estimated that nearly 50 per cent of the total population of the country requires employment although in many countries like China, Thailand etc. 55 per cent of total population is normally employed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So, taking the employment ratio of 50 per cent, the employment requirement of India is 52 crore which is again increasing by nearly 80 lakh per annum as the population is growing by 1.6 crore annually. As per official estimate, total employment in the country was 41 crore in 1999-2000 and it grew by at the rate of 41 lakh annually, during the period 1994-2000.

This official employment figure is somewhat inflated as it included disguised unemployment existing in rural areas of the country. But the level of unemployment existing at present is around 10 crore and that unemployment figure is again increasing by nearly 40 lakh per year due to our increasing size of population.

In view of the centrality of the employment objective in the overall process of socio-economic development as also to ensure availability of work opportunities in sufficient numbers, a special group on targeting ten million employment per year over the Tenth Plan period was constituted by Planning Commission under the Chairmanship of Dr. S.P. Gupta, Member, Planning Commission.

Considering the need for generating employment opportunities which are gainful, the Special Group has recommended the use of Current Daily Status (CDS) for measuring employment, as this measure of employment is net of the varying degrees of underemployment experienced by those who are otherwise classified employed on usual status basis.

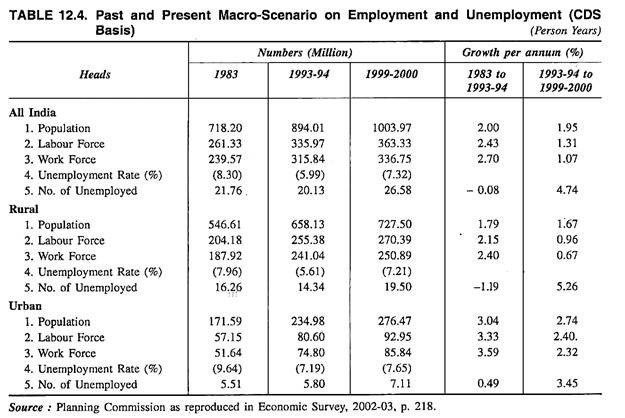

The Special Group has made following estimate of employment and unemployment in India on current daily status (CDS) basis.

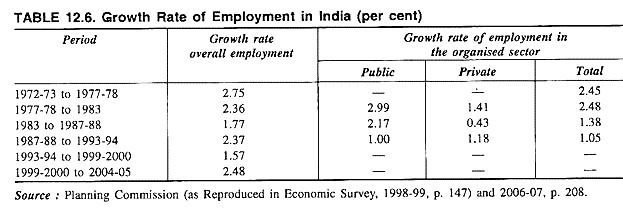

Table 12.4 reveals that the Export Group estimates has shown a decline in the rate of growth of population (from 2.0 to 1.95 per cent), labour force (from 2.43 to 1.31 per cent) and work force (from 2.70 to 1.07 per cent) during the period 1983-94 to 1994-2000.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But unemployment rate in the country during the period 1993-94 to 1999-2000 increased from 5.99 per cent to 7.32 per cent although the overall growth performance of the economy has been better in recent times than the previous decade (1983-94).

During the same period, the unemployment rate in rural areas of the country increased from 5.61 per cent to 7.21 per cent and the same unemployment rate in urban areas of the country also increased from 7.19 per cent to 7.65 per cent.

Total number of unemployed also increased from 20.13 million in 1993-94 to 26.58 million in 1999- 2000 out of which the rural and urban number of unemployed stood at 19.50 million and 7.11 million respectively in 1999-2000.

Finally, as per the data available from 939 employment exchanges in the country, the number of job seekers registered with employment exchanges as on September, 2002 (all of whom are not necessarily unemployed) was of the order of 4.16 crore out of which approximately 70 per cent are educated (up to 10th standard and above).

The number of women job seekers registered was of the order of 1.08 crore (26 per cent of the total job seekers). The maximum number of job seekers awaiting employment were in West Bengal (63.6 lakh), while the minimum were in the UT of Dadra & Nagar Haveli (0.06 lakh) and in the state of Arunachal Pradesh (0.2 lakh).

The placement was maximum in Gujarat whereas the registration was maximum in U.P. The placement effected by the employment exchanges at all India level during 2001 was of the order of 1.69 lakh as against 3.04 lakh vacancies notified during this period.

The National Sample Survey Organisation (NSSO), as per one of its recent surveys made in 2003 observed that the proportionate unemployment rate in India at present stands at 2.0 per cent of the total population and around 3.0 per cent of the total work force of the country.

Findings of NSS Survey 61st Round (2004-05):

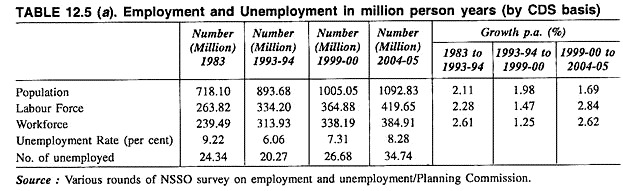

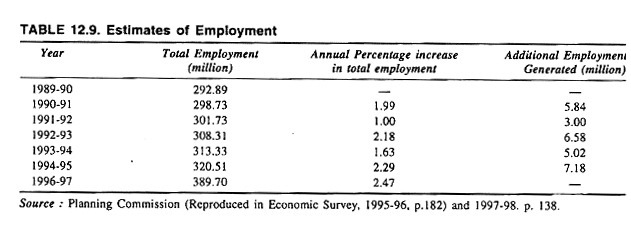

The latest and seventh quinquennial NSSO, Survey, namely 61st round conducted during July 2004 to June 2005 constituted an important source of information on employment and unemployment. The 6ist round of NSSO survey revealed a faster increase in employment during 1999-2000 to 2004-05 as compared to 1993- 94 to 1999-2000. Table 12.5 has clarified the position in this regard.

It would now be better to look at the current estimates of employment and unemployment in the country made by Planning Commission. In the meantime, the Eleventh Five year Flan has largely used the Current Daily Status (CDS) basis of estimation of employment and unemployment in the country.

It has also been observed that the estimates based on daily status are the most inclusive rate of ‘unemployment’ giving the average level of unemployment on a day during the survey year.

It captures the unemployed days of the chronically unemployed, the unemployed days of usually employed who became intermittently unemployed during the reference week and unemployed days of those classified as employed according to the criterion of current weekly status. Table 12.5(a) shows the estimates of employment and unemployment on CDS basis.

Table 12.5(a) reveals the trend in respect of population as well as labour force and workforce since 1983 to 2004-05 and the resultant difference between these two figures also shows the number of unemployed in different periods. With the increase in the population of the country, the number of labour force is increasing faster than the number of work force resulting growing number of unemployment in the country.

In 1983, total number of labour force in India was 263.82 million, total number of work force was 239.49 million and the resultant number of unemployed was 24.33 million. In 2004-05, total labour force of the country was 419.65 million and total work force was 384.91 million and as a result total number of unemployed increased to 34.74 million in 2004-05.

However, the growth of labour force in per cent per annum increased from 2.28 per cent during the period 1983 to 1993-94 to 2.84 per cent during the period 1999-00 to 2004-05. But the growth of work force in per cent per annum increased from 2.61 per cent during the period 1983 to 1993-94 to 2.62 per cent during the period 1999-00 to 2004-05.

Moreover, the unemployment rate as a proportion of labour force decreased from 9.22 per cent in 1983 to 6.06 per cent in 1993-94 and then gradually increased to 8.28 per cent in 2004-05.

Estimates on employment and unemployment on CDS basis [Table 12.5(a)] indicate that employment growth during 1999-2000 to 2004-05 has accelerated significantly as compared to the growth witnessed during 1993-94 to 1999-2000. During 1999-2000 to 2004-05, about 47 million work opportunities were created compared to only 24 million in the period between 1993-94 and 1999-00.

Employment growth accelerated from 1.25 per cent per annum to 2.62 per cent per annum. However, since the labour force grew at a faster rate of 2.84 per cent than the workforce, unemployment rate also rose.

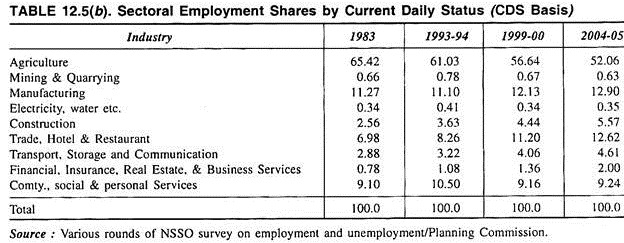

The incidence of unemployment on CDS basis increased from 7.31 per cent in 1999-00 to 8.28 per cent in 2004-05. It would also be better to look at the sectoral employment shares by current daily status in the country. Table 12.5(b) will clarify the position in this respect.

Table 12.5(b) reveals the sectoral employment shares of different sector of the country in recent years. The decline in overall growth of employment during 1993-94 to 1999-00 was largely due to the lower absorption in agriculture. The share of agriculture in total employment dropped from 61 per cent to 57 per cent.

This trend continued and the share of agriculture in total employment further dropped to 52 per cent in 2004-05.

While the manufacturing sector’s share increased marginally during this period, trade, hotel and restaurant sector contributed significantly higher to the overall employment than in earlier years. The other important sectors whose shares in employment have increased are transport, storage and communications apart from financial, insurance, real estate, business and community, social and personal services [Table 12.5.(b)].

Extent of Farm Unemployment:

A high degree of unemployment and underemployment prevails among the agricultural workers of the country. This farm or agricultural unemployment is prevailing in the form of seasonal unemployment, disguised unemployment and chronic and usual status unemployment.

To measure the extent of unemployment and underemployment is really a difficult task. As per the N.S.S. study the daily status rural unemployment rate in India was 5.25 per cent in 1987-88.

The Agricultural Labour Enquiry Committee Report (First and Second) revealed that in India agricultural labourers had 275 and 237 days of employment in 1950-61 and 1956-57 respectively. Considering the fall in the employment elasticity with reference to GDP for the agricultural sector during the 1970s and 1980s it can be guessed that the seasonal unemployment might have increased in recent years.

In respect of disguised unemployment various estimates have been made to determine the extent of surplus labour in India by Shakuntala Mehera, J.P. Bhattacharjee, Ashok Rudra, J.S. Uppal and others. Among these works, Shakuntala Mehera’s work was quite well known.

She estimated that the extent of surplus work force in agriculture was 17.1 per cent during 1960s. Again on the basis of 32nd Round of the NSS, the Usual status of rural unemployment in March 1985 was estimated at 7.8 million and such unemployment was highest in the age-group of 15-29.

Recently, a study to estimate the extent of farm unemployment was conducted by Lucknow based Centre of Advanced Development Research (CADR). The report submitted by this centre in September 1992 revealed that a very high degree of unemployment or under-employment prevails among the 160 million Indians engaged in agriculture, either as cultivators or labourers.

It is found that these rural people do not get even the minimum work opportunity of 270 days a year, the average being only 180 days. This indicates that only 100 million people are sufficient to carry out the entire agricultural operations, including those of animal husbandry. Thus as many as 60 million people are at present left with virtually no work in agriculture and allied activities.

The study also highlighted the inter-state variation in agricultural labour absorption capacity. Among all the states, only in four states—Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and Kerala—-agriculture provides full work opportunities of 270 days of eight-hour duration to every worker.

But in states like Andhra Pradesh, Bihar and Tamil Nadu, employment in agriculture is available to less than 50 per cent of the workforce while Karnataka, Maharashtra and Uttar Pradesh too have inadequate labour absorption capacity in the rural areas.

The CADR estimated that the agricultural sector will be able to absorb only 120 million of the available 180 million people by the end of the present century provided the rate of labour replacement by mechanization is not accelerated.

The report revealed that most of the unemployed or underemployed people are concentrated in the states of Uttar Pradesh (104 lakh), Bihar (100 lakh), Andhra Pradesh (80 lakh) and Tamil Nadu (66 lakh).

Extent of Urban Unemployment:

In India urban unemployment has been recording a serious proportion from the very beginning. The estimates of urban unemployment were made by the Planning Commission, the Central Statistical Organisation (CSO), Ministry of Labour and Employment and some individual economists like W. Malenbaum, R.C. Bhardwaj at different times.

Although these estimates are not comparable due to differences in concepts adopted, but these estimates provide some idea about the quantum of urban unemployment.

These reports revealed that during the first decade of planning the quantum of urban unemployment increased from 2.5 million in 1951 to 4.5 million in 1961, i.e., about 11.4 to 15.5 per cent of the working population remained unemployed. Again the extent of urban unemployment increased to 6.5 million in 1985 (as per NSS 32nd Round) and the rate of urban unemployment was 9.7 per cent.

This urban unemployment is mostly of two types:

(a) Industrial unemployment and

(b) Educated unemployment.

In India due to growing industrial sickness in huge number of small scale industrial units and in some large scale units, the quantum of industrial unemployment has been increasing at an alarming rate. Moreover, the recent structural adjustments in industrial sector will also add a good number of unemployment to this category. However, the exact number of industrial unemployment in India is not available in the absence of proper data.

Educated Unemployment:

Educated unemployment in India which is contributing a significant portion of urban unemployment has been increasing at a very rapid scale. Total number of educated unemployment in India increased from 2.4 lakh in 1951 to 5.9 lakh in 1961 and then to 22.96 lakh in 1971.

Again the number of educated job seekers increased from 90.18 lakh in 1981 to 167.35 lakh in 1987 and then to 291.2 lakh in 2002 which constituted about 74 per cent of the total job seekers of the country.

Unemployment Rates by Level of Education:

NSSO data indicates that compared to 1993-94, unemployment rates for persons of higher education level has declined in rural areas both for males and females in 1999-2000 and it has further declined in 2004- 05 compared to 1999-2000.

Unemployment rate of graduate and above female population is much higher in rural areas than in urban areas which is indicative of lack of opportunities in rural India combined with lack of mobility of this population segment.

Sluggish Employment Growth in Recent Times:

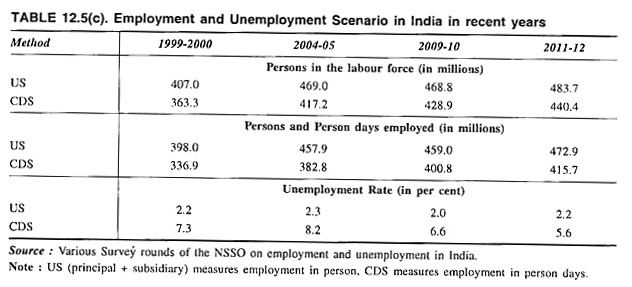

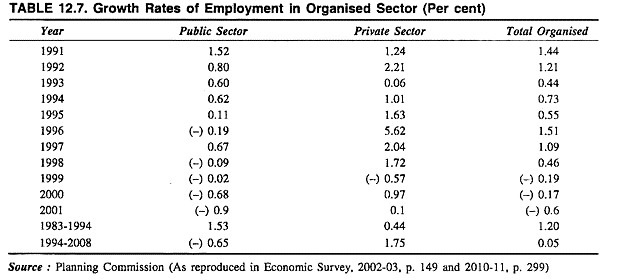

In recent times, .there is a slump in the rate of growth of employment. An important cause of concern is the declaration in the annual compound growth rate (CAGR) of employment during 2004-05 to 2011-12 to 0.5 per cent from 2.8 per cent during 1999-2000 to 2004-05 as against CAGRs of 2.9 per cent and 0.4 per cent respectively in the labour force for the same periods. Table 12.5(c) will clarify this situation.

Table 12.5(c) reveals that as per the National Sample Survey Office (NSSO) data during 1999-2000 to 2004-05, employment on usual states (US) basis increased by 59.9 million persons from 398.0 million to 457.9 million as against the increase in labour force by 62.0 million persons from 407.0 million to 469.0 million.

After a period of slow progress during 2004-05 to 2009-10, employment generation picked up during 2009-10 to 2011-12, adding 13.9 million persons to the workforce, but not keeping pace with the increase in labour force (14.9 million persons) as shown in the table.

Again, based on current daily status (CDS), CAGR in employment was 1.2 per cent and 2.6 per cent against 2.8 per cent and 0.8 per cent in the labour force respectively for the same periods.

However, the country has been experiencing structural changes in its employment pattern in recent times. Thus for the first time, the share of primary sector in total employment of the country dipped below the half way mark as its share declined from 58.5 per cent in 2004-05 to 48.9 per cent in 2011-12.

But the employment in the secondary and tertiary sectors increased to 24.3 per cent and 26.8 per cent respectively in 2011-12 as compared to 18.1 per cent and 23.4 per cent respectively attained in 2004-05. Moreover, self-employment continues to dominate by attaining 52.2 per cent share in total employment in the year 2011-12. But what is critical is the significant share of workers are engaged in low income generating activities.

Moreover, there are other issues of concern such as poor employment growth in rural areas, especially among females. Though employment of rural males is slightly better than that of females, long term trends indicate a low and stagnant growth. Such trends call for diversification of livelihood in rural areas from agricultural to non-agricultural activities.

Besides, a major impediment to the pace of quality employment generation in India is the small share of manufacturing in total employment. However, the data available, from 68th round of NSSO (2011-12) indicates a revival in employment growth in manufacturing from 11 per cent in 2009-10 to 12.6 per cent in 2011-12.

Moreover, the usual status (US) unemployment rate is generally regarded as the measure of chronic open unemployment during the reference year while the current daily status (CDS) is considered as a comprehensive measure of unemployment, including both chronic and invisible unemployment. Thus, while chronic open unemployment rate in India hovers around a low 2 per cent, it is significant in absolute terms.

The number of unemployed people (under US) declined from 11.3 million during 2004-05 to 9.8 million in 2009-10 but again increased to 10.8 million in 2011.12. However, on the basis of CDS, the number of unemployed person days declined from 34.3 million in 2004-05 to 28.0 million in 2009-10 and further to 24.7 million in 2011- 12.

It is also observed [from Table 12.5(c)] that there has been a significant reduction in chronic and invisible unemployment from 8.2 per cent in 2004-05 to 5.6 per cent in 2011-12. Expert feels that despite only a marginal growth in employment between 2009-10 and 2011-12, the main reason for the decline in unemployment levels could be that an increasing proportion of the young population opts for education rather than participating in the labour market. This is reflected from the fact that there is a rise in enrolment growth in higher education from 4.9 million in 1990-91 to 29.6 million in 2012-13.

Salient Features of the Trend of Unemployment Rates in India in Recent Years:

Following are some of the salient features of the trend of unemployment rates in India:

i. The unemployment rate went up between 1993-94 to 2004. On the basis of the current daily status (Unemployed on an average in the reference week) during the reference period unemployment rate for males increased from 5.6 per cent to 9.0 per cent in rural areas and from 6.7 per cent to 8.1 per cent in urban areas.

ii. The unemployment rate for female increased from 5.6 per cent in 1993-94 to 9.4 per cent in 2004 in rural areas and from 10.5 per cent to 11.7 per cent in urban areas.

iii. Furthermore, it is found that unemployment rates on the basis of current daily status were much higher than those on the basis of usual status (unemployed on an average in the reference year) implying a high degree of intermittent unemployment. This could be mainly because of the absence of regular employment for many workers.

iv. Urban unemployment rates (current daily status) were higher than rural unemployment rates for both males and females in 1993-94. However, in 2004, rural unemployment rates for males were higher than that of urban males.

v. Unemployment rates varied sharply across states. States, where wages are higher than in higher growing ones because of strong bargain or social security provisions; such as high minimum wage, had high incidence of unemployment in general.

Essay # 4. Causes of Unemployment Problem in India:

Unemployment problem in India is the cumulative result of so many factors.

The broad causes of unemployment problem are as follows:

(i) Population Explosion:

The most fundamental cause of large scale unemployment in India is the high rate of population growth since the early 1950s and the consequent increase in its labour force. It was estimated that with the 2.5 per cent annual rate of population growth, nearly 4 million persons are added to the labour force every year. To provide gainful employment to such a big number is really a difficult task.

(ii) Underdevelopment:

Indian economy continues to be underdeveloped even as a vast quantity of unutilized and under utilised natural resources are prevailing in the country. The scale and volume of economic activities are still small. The non-agricultural sector especially modern industrial sector which could generate huge number of employment, is growing very slowly.

During the pre-independence period also, Indian economy experienced a slow growth. British destroyed the indigenous small scale and cottage industries instead of expanding and modernising them. During the post- independence period also, the performance of the industrial sector has also been found far below the plan targets and needs.

Moreover, the slow rate of capital formation is also responsible for the hindrances in the path of realisation of growth potential in agriculture, industry and infrastructure sector. Thus this underdevelopment is largely responsible for slow expansion of employment opportunities.

(iii) Inadequate Employment Planning:

In the first phase economic planning in India, employment opportunities could not be increased adequately and little has been done to utilise the Nurksian variety of labour surplus existing in the rural areas. Moreover, weak manpower planning is also another serious gap in Indian planning.

Less effort has been made for balancing the manpower needs and supplies in various production sectors, indifferent regions of the country and also indifferent skills.

This has resulted to large imbalances in the sphere of educated and trained personnel like engineers, technicians, cost accountants, plain graduates and port graduates, administrators etc. Thus huge amount of resources used for developing manpower could not come into much help due to faulty manpower planning.

(iv) Slow Rate of Growth:

In India the rate of growth of the economy is very poor and even the actual growth rate lies far below the targeted rate. Thus the increased employment opportunities created under the successive plans could not keep pace with the additions to the labour force taking place in the country every year leading to a huge and larger backlog of unemployment at the end of each plan.

(v) Backwardness of the Agriculture:

Heavy pressure of population on land and the primitive methods of agricultural operations are responsible for colossal rural unemployment and underemployment in the country.

(vi) Insufficient Industrial Development:

Industrial development in the country is not at all sufficient. Rather the prospects of industrial development has never been completely realised. Due to dearth of capital, lack of proper technology, scarcity of industrial raw materials, shortage of electricity and lack of labour intensive investment industrial sector could not gain its momentum and also could not generate sufficient employment opportunities in the country.

(vii) Prevailing Education System:

The prevailing education system in India is full of defects as it fails to make any provision for imparting technical and vocational education. Huge number of matriculates, undergraduates and graduates are coming out every year leading to a increasing gap between job opportunities and job seekers among the educated middle class.

In the absence of vocational education and professional guidance, these huge number of educated youths cannot avail the scope of self-employment leading to growing frustration and discontent among the educated youths.

(viii) Slow Growth of Employment during Economic Reforms:

Finally, the current phase of economic reforms introduced in India has resulted jobless growth to some extent. Economic Reforms has resulted large scale retrenchment of surplus workers in different industries and administrative departments due to down-sizing of workers.

The annual growth rate of employment which was 2.40 per cent during the period 1983- 94, but the same rate declined to a mere 0.98 per cent during the period 1994-2000. As a result, the unemployment growth rates increased from 5.99 per cent in 1993-94 to 7.32 per cent in 1999-2000.

Essay # 5. Remedial Measures to Solve Unemployment Problem In India:

Unemployment problem is a serious problem faced by a large populous country like India. Thus it is quite appropriate to suggest some measures to solve this problem. In order to suggest appropriate measures to solve this problem, it is better to identify some measures separately for the problem of rural unemployment and urban unemployment.

A. Remedies to Rural Unemployment Problem:

As the nature of rural unemployment is quite different, it is better to suggest some special measures to solve this problem.

Following are some of these measures:

(i) Expanding Volume of Rural Works:

One of the most important remedial measures to solve the problem of unemployment is to expand the opportunities for work especially in rural areas. In order to clear the backlog of unemployment and also to provide jobs to additional labor force joining the mainstream workers, this expansion in the volume of works needs to be done rapidly and that too in the areas of both wage employment and self-employment.

As large scale industries cannot provide adequate employment opportunities thus more importance be given to the development of agriculture and the allied sector along with development of small scale and cottage industries and also the unorganised informal sector and the services sector.

(ii) Modernisation of Agriculture:

In order to eradicate the problem of rural unemployment, the agricultural sector of the country is to be modernized in almost all the states. This would derive considerable agricultural surplus which would ultimately boost the rural economy and also expand employment opportunities in the rural areas. Attempts should also be made for wasteland development and diversification of agricultural activities.

(iii) Development of Allied Sector:

The problem of rural unemployment can be tackled adequately by developing allied sector which includes activities like dairy farming, poultry farming, bee keeping, fishery, horticulture, sericulture, agro processing etc. which are having a huge potential for the generation of employment and self-employment opportunities in the rural areas of the country.

(iv) Development of Rural Non-Farm Activities:

In order to generate employment opportunities in the rural areas, development of rural non-farm activities, viz., rural industries, the decentralised and cottage small scale sector of industry, agro-based industry, rural informal sector and the services sector, expansion of rural infrastructure, housing, health and educational services in the rural areas etc. should be undertaken throughout the country with active government support. Since Eighth Plan, the Government is following this strategy for the generation of rural employment.

(v) Appropriate mix of Production Techniques:

Although Mahalanobis strategy of development argued in favour of capital intensive techniques but in order to tackle the problem of rural unemployment the government should adopt a appropriate mix of production techniques where both the labour intensive and capital intensive methods, of production should be adopted selectively in the new fields of production so as to attain both growth in employment along with its efficiency.

(vi) Rural Development Schemes:

In order to eradicate the problem of rural unemployment, the Central as well as the State Governments should work seriously for introducing and implementing rural development schemes so that the benefit of such development could reach the target groups of people in time.

(vii) Decentralisation:

In order to reduce the extent of the problem of rural unemployment it would be quite important to spread the location of industries around the small towns on the basis of local endowment position so that migration of people from rural to urban areas can be checked.

(viii) Extension of Social Services:

It is also important to extend the social services in the rural areas in the sphere of education, medical science and in other areas which will go a long way for the empowerment of the rural people in general. Such a situation will indirectly motivate the people towards self-employment.

(ix) Population Control:

Adequate stress should be laid on the control of growth of population through family welfare programmes especially in the rural and backward areas of the country. This would be conducive for solving the growing problem of rural unemployment of the country as a whole.

(x) SHGs and Micro Finance:

Adequate steps be taken for promoting self help groups (SHGs) for generating self employment opportunities. In this respect, micro finance flow through NGOs towards SHGs can play a responsible role in solving the problem of rural unemployment.

B. Remedies to Urban Unemployment Problem:

In order to solve the problem of urban unemployment the country should follow certain important measures.

Following are some of these measures:

(i) Rapid Development of Industries:

In order to solve the problem of urban unemployment, immediate steps must be taken for enhancing the industrial efficiency. In this regard, immediate attempts must be made for expansion and modernisation of existing industries in cost-effective manner and also for setting up of new industries.

Some basic and heavy industries which were already established in the field of iron and steel, chemicals, defence goods, heavy machineries, power generation, atomic energy etc. should be modernized and more such new industries should also set up in the new and existing fields for generating huge number of employment opportunities for the present and coming generations.

More new resource based and demand based industries should be set up for generating employment opportunities.

(ii) Revamping Education System:

Indian education system still largely remains very much backward and fails to meet the demand for present industries and administrative set up. Instead of giving too much stress on general education, stress should be laid on vocationalisation of education which would help the younger generation to involve themselves in small scale and cottage industries and also in the services sector.

(iii) Motivation for Self-Employment:

In order to change the mindset of younger generation, especially from urban areas, attempts must be made by both government and non-government agencies for motivating the young people to accept the path of self-employment in the contest of squeezing scope of employment through carrier counseling at the institutional level.

(iv) Development of SSIs:

Considering the huge number of unemployed, it is quite important to develop a good number of small scale and cottage industries by adopting labour-intensive approach. Developing such S.S.Is for the production of need-based products would help a lot for generating huge employment opportunities in urban and semi-urban areas.

(v) Development of Urban Informal Sector:

As a good number urban people are engaged in urban informal sector, thus adequate steps must be taken for the improvement and modernisation of this informal sector so as to expand the sector further and also to generate more such employment opportunities for the growing number of urban unemployed person.

(vi) Revamping the Role of Employment Exchange:

In order to utilise the huge governmental set up of Employment Exchange throughout the country it is quite important to change the role of such exchanges for motivating and guiding the younger generations for self-employment in addition to its existing role for registration and placement.

(vii) Banking Support:

In order to solve the problem of urban unemployment, the scheduled commercial banks should come forward with rational proposals for the development of SSIs, various units in the services sector and also for the development of urban informal sector with a sympathetic attitude.

(viii) Works of National Interest:

In order to solve the problem of urban unemployment it is quite necessary to start the work of national interest which would generate adequate employment opportunities in the urban areas.

(ix) Changing Pattern of Investment:

Attempt should also be made to change the pattern of investment into a viable and productive one both from economic and social point of view so as to generate employment opportunities.

(x) Government Support:

In order to tackle the problem of urban unemployment, the government should come forward with viable urban employment generation schemes in the line of PMRY, NRY etc. to assist the urban unemployed for self-employment projects.

(xi) Growing Participation of FDI:

In order to tackle the problem of urban unemployment, the government should follow a suitable policy in the line of China for promoting the smooth flow of foreign direct investment (FDI) into our country for its growing participation in various important industrial and infrastructural projects.

C. General Remedies to Unemployment Problems:

(i) Special Employment Programmes:

In order to meet the gap between the requirement and the actual generation of employment opportunities, special employment programmes must be undertaken as an interim measure till the economy could reach the maturity level of securing jobs for everyone.

These kind of supplementary programmes are very important for the poor people residing in both rural and urban areas and also residing in small 8 medium towns.

Seasonally unemployed can also be offered seasonal employment through such special employment programmes. Moreover backward people like landless agricultural labourers, marginal formers, rural artisans, tribal people settled in remote and hilly areas can also be benefited from such progrmmes.

The programmes may be chalked out by providing direct wage employment as on rural capital works or in the form of providing assets or providing inputs to those people for self-employment. Currently, the steps taken by the government for the implementation of NREGA is a right step in this direction.

(ii) Raising the Rate of Capital Formation:

In order to reduce the problem of unemployment, in general, it is quite necessary to raise the rate of capital formation in the country. Raising the rate of Capital formation is necessary to expand the volume of work.

Capital formation can directly generate employment in the capital goods sector. Raising the capital formation helps the country to raise its capital-stock and thereby can raise the productivity of workers by raising the volume of capital available per workers.

(iii) Manpower Planning:

Management of human resources in a right and scientific manner is quite important for solving the problem of unemployment. This is important for ensuring promotion of employment scope as well as for realization of development of the economy. All these call for proper manpower planning which requires the following measures.

Firstly, going beyond the narrow domain of manpower planning simply related to matching demand and supply of skilled personnel, it is quite important to adopt effective remedies to cut down the growth rate of population which in turn reduce the growth rate of labour supply after a gap of period and thereby reducing the problem of unemployment.

Secondly, in order to attain effective use of skills it is essential to tailor the supply of skilled labour as per the it’s requirement so that excess or shortages in skills in different sectors are not faced.

Thirdly, while continuing with present strategy to promote high level skill formation through education and Training confined to a small proportion of labour force, it is also essential to improve the capabilities of large number of general people for their development.

This calls for several inter-related measures like making provision for adequate food and nutrition, elementary education, proper health facilities, training for jobs etc.

Fourthly, while introducing special programmes for employment, it is quite essential to ensure that the programmes rightly matches the characteristics and abilities of targeted group and also match with the overall development plans of various sectors. This will definitely make schemes quite useful and meaningful.

Essay # 6. Characteristics of Employment Policy Followed in India–Its Critical Evaluation:

Since the inception of planning, the Government of India has been pursuing its employment policy for eliminating the problems of unemployment.

The following are of its broad characteristics:

(i) Multi-Faceted:

As the unemployment problem in India is multi-dimensional thus the policy followed by the government to tackle this problem is multi-faceted our which constitutes many-sided approach. Thus the employment policy followed in India constitutes many sub-policies to tackle various forms of unemployment including under employment.

(ii) Emphasis on Self-Employment:

The employment policy of India has given due emphasis on self- employment as a small proportion of our labour force is engaged through wage employment and the majority (56 per cent) of the workforce is self-employed.

Thus the employment policy makes provision for training of skills, supply of inputs, marketing of products, extending loan etc. so as to make them self-employed in various activities, like agriculture and allied activities, village and small industries, non-farm activities and also in informal sector.

(iii) Emphasis on Productive Employment and Asset Creation:

Employment policy of our country lays stress on creation of productive employment and also on creation of assets for the poor workers.

(iv) Employment Generation:

With the growth of various sectors, the employment policy gave due stress an employment generation at a targeted growth rate fixed under different plans through different employment generation programmes like NREP, RLEGP, JRY etc.

(v) Special Employment Programmes:

Employment policy of India has incorporated different special employment programmes both for rural and urban areas. These includes IRDP, TRYSEM, DWCRA, JGSY, JRY, EAS, AGSY, etc. for rural areas and PMRY, SJSRU, NRY etc. for urban areas.

(vi) Employment for the Educated:

Employment policy has made provision for tackling the educated unemployment prevailing both in rural and urban areas through employment schemes related to processing, banking, trading, marketing etc.

(vii) Manpower Planning:

The employment policy has taken certain measures for ensuring proper development of human resources and also through right deployment. Stress is given on attaining balancing of demand and supply of skilled manpower.

Critical Evaluation:

It is important to make critical evaluation of the employment policy followed in India both in terms of achievements and failures. Undoubtedly some increase in employment has taken place in all the sectors of the country since 1951, more specially in recent times.

The average growth rate of employment per annum from 2.7 per cent during 1983-94 to 1.0 per cent during 1994-2000. During 1998-99 and 1999-2000, the overall growth rate of employment in the organised public and private sector remained negative.

Moreover a significant portion of the employment generated has been able to benefit the poor and weaker sections of the population and helped a number of them to reach above the poverty line.

However, improvement that has taken place on the employment front can be considered inadequate for the growing number of unemployed. The large number of people still lying below the poverty line is a pointer to such inadequacy. Even then it is quite important to point out some of the positive and negative aspects of the policy of employment followed by the government.

Positive Aspects of the Policy:

Since the inception of planning, the broad perception of employment generation followed in our country has been found largely correct. The following four components of the employment policy usually favoured employment generation on a major scale. Firstly, since the second plan, our policy has been approaching to the long term perspective of full employment at higher incomes.

Development of modern industries along with capital goods industries including infrastructure would strengthen the economy and help reach high income employment at a later stage.

Secondly, provision has been made for the promotion of labour intensive small scale and cottage industries, Thirdly, considering the inadequate employment growth achieved through industrial activities, the policy devised special employment programmes for generating jobs work to rural and vulnerable sections of population. Fourthly, employment policy pursued in the country helped to attain self-employment of a faster rate than wage employment.

Weaknesses of the Policy:

However, the employment policy followed India is not free from faults. The faults are mostly related to its unsatisfactory implementation and inadequate employment orientation as discussed in the following manner.

Firstly, unsatisfactory implementation of the policy has been mostly related to long term slow growth of the economy, widespread industrial sickness and retrogression in growth in industrial sector since mid- sixties.

Moreover, it was also related to slow and poor execution of special employment programmes. Secondly, the faults in the employment policy are mostly related to inadequate attention to full employment except in the Ninth and Tenth Plan, where measures like too much emphasis on capital intensive investment and lesser emphasis on labour intensive investment, inadequate steps to absorb labour surpluses and inadequate arrangement for manpower planning educated and skilled personnel were taken.

Essay # 7. Employment Policy and Schemes in India:

Since the Third Five Year Plan, the Government of India launched certain special programmes for removing unemployment problem in the country. With that purpose, the Government of India, set up Bhagawati Committee to suggest measures for solving growing unemployment problem in the country.

The Bhagawati Committee submitted its report in 1973 and suggested various schemes like rural electrification, road building, rural housing and minor irrigation works. Accordingly, the Government undertook various programmes to generate employment opportunities and to alleviate under-employment prevailing in the country.

These programmes were as follows:

(a) Rural Works Programmes:

This programme was undertaken to generate employment opportunities for 2.5 million persons and also for the construction of civil works of a permanent nature. But this programme generated employment only to the extent of 4 lakh persons only.

(b) Marginal Farmers and Agricultural Labourers Development Agencies (MFALDA):

During the Fourth Plan this scheme was introduced for marginal farmers and agricultural labourers for assisting them with subsidized credit support for agricultural and subsidiary occupations like horticulture, dairy, poultry, fishery etc.

(c) Small Farmers’ Development Agencies (SFDA):

This scheme was also introduced during the Fourth Plan with the object to provide small farmers credit so that they, could avail latest technology for intensive agriculture and also could diversify their activities.

(d) Half-a million Job Programme:

To tackle the problem of educated unemployment, a special programme—”Half a million job programme” was introduced. In 1973-74, provision of Rs 100 crore was made and different states and Union Territories were asked to formulate and implement this scheme for securing an employment opportunities for definite number of persons.

(e) Job education for unemployed:

In 1972-73, another programme for educated unemployed and for highly qualified engineers, technologists and scientists were prepared. Under this scheme, a sum of Rs 9.81 crore was allotted to the states which created 45,000 job opportunities for the educated persons.

(f) Drought Area Programme:

This programme was introduced for the economic development of certain vulnerable areas by organising productive and labour-intensive programmes like medium and minor irrigation, soil conservation, afforestation and road construction. During 1970-72, the government spent Rs 30.80 crore, generating employment about 4.70 million man-days and in 1972-73 by spending Rs 38.51 crore about 40 million man-days of employment was generated.

(g) Crash programme for rural employment:

This scheme was introduced in 1971-72 for generating additional employment through the introduction of various productive and labour-intensive rural projects.

The main objectives of these programmes were to provide employment to 100 persons on an average to each block over the working seasons of 10 months in every year and secondly to produce durable assets. But the various schemes introduced during the Fourth Plan could not succeed in solving the problem of rural unemployment and underemployment.

Employment Policy in the Fifth Plan:

The Fifth Plan document laid emphasis on the generation of employment in rural areas and aimed at absorbing the increments in the labour force during the plan period by stepping up rates of public investment.

(h) Food-For-Work-Scheme:

This scheme was introduced in April 1977 for benefitting the rural poor and more particularly the landless agricultural labourers. Under this scheme, a part of wages those workers engaged in rural works was paid in terms of food grains. The Central Government supplied these food grains to the State Government free of charge. In this way off-season employments were made available to rural unemployed.

Employment Policy in the Sixth Plan:

The Sixth Plan in its Employment Policy admits, “In the field of employment the picture has been far from satisfactory. The number of unemployed and under-employed has risen significantly over the last decade. In the above context therefore our employment policy should cover two major goals: Reducing underemployment by increasing the rate of growth of the gainfully employed and reducing unemployment on the basis of usual status commonly known as open unemployment”.

(i) National Rural Employment Programme:

In October, 1980, the NREP replaced the Food-for- work programme. In this programme State Governments received central assistance both in the form of food grains and cash for undertaking productive works in the rural areas.

During the Sixth Plan, total expenditure incurred by both the Central and State Government were of the order of Rs 1,837 crore and total food grains utilisation was 20.57 lakh tonnes. Total employment generation under this programme during the Sixth Plan was 1,775 million man-days.

During the Sixth Plan overall employment increased by 35.60 million standard person year (SPY) as against the target of 34.28 million SPY. During the Sixth Plan the growth rate of employment was 4.32 per cent per annum. During the Sixth Plan other programmes like IRDP and RLEGP were introduced.

Employment Policy in the Seventh Plan:

During the Seventh Plan, the magnitude of employment requirement was worked out at 47.58 million. Accordingly, the Seventh Plan document mentioned: “It is expected that additional employment of the order of 40.36 million standard person years would be generated during the Seventh Plan with an implied growth rate of 3.99 per cent per annum.

The special employment programmes of NREP and RLEGP would generate 2.26 million standard persons years of employment in 1989-90. The employment generation of IRDP has been estimated as 3 million SPY mainly concentrated in agriculture and other sectors”. Thus the Seventh Plan decided to supplement the efforts of employment generation by direct employment programmes like IRDP, NREP, RLEGP and TRYSEM.

(j) Integrated Rural Development Programme (IRDP):

The Sixth Plan proposed to integrate multiplicity of agencies for providing rural employment like Employment Guarantee Scheme, SFDA, MFALDA, Drought Prone Area Programme, Command Area Development Programme etc. Accordingly, on 2nd October 1980, the Integrated Rural Development Programme was introduced.

This programme was a multi-pronged attack on the problem of rural development and was designed as an anti-poverty programme. During the Sixth Plan this programme was initiated in all the 5,011 blocks of the country. To implement this scheme one District Rural Development Agency was established in every district.

During the Sixth Plan, a sum of Rs 1,661 crore was spent on this programme as against the provision of Rs 1,500 crore and the total number of beneficiaries covered during the plan period was 16.56 million as against the target of 15 million.

The Seventh Plan set a target to assist 20 million households under IRDP and the total allocation under this programme was Rs 3,474 crore. During this plan about 18.2 million families were assisted and about Rs 3,316 crore was utilised.

(k) Rural Landless Employment Guarantee Programme (RLEGP):

The Rural Landless Employment Guarantee Programme was introduced on 15th August, 1983 with the sole object of generating gainful employment opportunities, to create productive assets in rural areas and for improving the overall quality of rural life.

In this programme preference in employment is given to landless labourers, women scheduled caste and scheduled tribes. This programme is funded fully by the Central Government.

During the Seventh Plan, Rs 1,744 crore was provided by the central sector to generate 1,013 million man-days of employment during the plan period. But during the first three years of the plan Rs 1,743 crore was utilised and generated employment to the extent of 858 million man-days only. Thus 85 per cent of the target was only realised.

NREP:

The Seventh Plan had earmarked a total outlay of Rs 2,487 crore for the National Rural Employment Programme out of which centre sanctioned Rs 1,251 crore. The Seventh Plan sets a target to generate employment to the extent of 1,445 million man-days. But during the first four years of the Seventh Plan nearly Rs 2,940 crore were spent under NREP generating 1,447.7 million man-days of employment which has fulfilled plan target.

Jawahar Rozgar Yojana (JRY):

Jawahar Rozgar Yojana was launched on 28th April, 1989 by the Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi. Under the programme, all the existing rural wage employment programmes like National Rural Employment Programme and Rural Employment Committee Programme were merged.

The programme (JRY) aims at reaching each and every panchayats of the country. In this programme 80 per cent of resources would be funded by the centre and the rest 20 per cent by the States. In the year 1989-90, the centre made a provision of Rs 2,100 crore.

In this programme allocation of funds to the State is being made in proportion to the size of their population below the poverty line. In this programme, on an average a village panchayat with its population of 3,000 to 4,000 people will receive between Rs 80,000 to Rs 1 lakh every year. It was also decided to provide employment to at least one member in each poor family for at least 50 to 100 days in a year.

Besides this, the National Scheme of Training of Rural Youth for Self Employment (TRYSEM) was also introduced in the country. This programme was meant for generating self-employment opportunities by imparting training to the rural youths in various trades and skills.

Thus considering all these programmes introduced in the employment policy of the country under different plans, it can be concluded that these programmes could not make much headway in solving both the rural and urban unemployment in the country.

Employment Policy in the Eighth Plan:

Although various employment generation schemes were implemented till the completion of the Seventh Plan, the problem of unemployment faced by the country still remains grave. Total unemployment in the country totaled 23 million in the year 1992. In 1981-91, the country registered a 2.1 per cent growth rate in population while the growth rate of the labour force was 2.5 per cent per annum.

In 1991, the total population of the country was estimated at 837 million of which the labour force constituted about 315 million. Thus the growth of the labour force has been higher than the population growth but the growth rate of employment, which remained only 2.2 per cent per annum during the period 1971-91, has remained lower than of labour force.

It has been estimated that the country will have 94 million unemployment by the year 2002. Thus in Order to wipe out the projected unemployment in the country completely by 2002, the country should achieve the required annual employment growth rate between 2.6 to 2.8 per cent. As unemployment is a major socio-economic problem it must be tackled on a priority basis.

At the outset of the Eighth Five Year Plan (1992-97), employment was estimated to be about 301.7 million. The open unemployment was estimated at 17 million, of which the educated unemployment accounted for 7 million. Severe under-employment was estimated as 6 million. Thus the backlog of unemployment for planning purposes was thus reckoned at 23 million in April 1992.

As the net additions to labour force during the Eighth Plan and during the period 1997-2002 were estimated at 35 million and 36 million respectively, in order to reduce unemployment to negligible levels by 2002, the employment should grow at the average annual rate of about 2.6 to 2.8 per cent over the ten year period 1992-2002.

Considering the present unemployment scenario, the Eighth Five Year Plan sought to achieve 2.6 per cent rate of growth of employment, corresponding to an average annual growth rate of GDP of 5.6 per cent envisaged in the plan.

Thus the Eighth Plan emphasised the need for a high rate of economic growth, combined with a faster growth of sectors, sub-sectors and areas which have relatively high employment potential for enhancing the pace of employment generation.

The plan sought to achieve the target by laying emphasis on a crop-wise and geographic diversification of agricultural growth, wasteland development, promotion of agro-based activities, rural non-farm activities including rural industries, the decentralised and small scale sector of industry, the urban informal sector and the services sector, expansion of rural infrastructure, housing and health and educational services especially in rural areas, revamping of the training system and streamlining of the special employment programmes to integrate them with area development plans.

Thus all these above are considered as basic elements of the employment oriented growth strategy envisaged in the plan. Additional employment opportunities to the extent of 8 to 9 million per year, on an average, during the Eighth Plan period and of the order of 9 to 10 million per year, on an average, during 1997-2002 period are expected to be generated.

Thus the employment strategy as envisaged in the Eighth Plan generated around 42.5 million additional employment during the period 1992-97. The continuation of the strategy during the Ninth Plan period generated around 47.5 million additional employment during the period 1997-2002.

Thus the employment strategy wiped out the entire backlog of open unemployment and a sizable part of the severe under-employment in the country.

The Eighth Plan document has also identified various problems as factor responsible for the lower growth of employment in the country. These include:

i. Mismatch between skill requirement and employment opportunities;

ii. Low technology, low productivity and low wage;

iii. Occupational shifts from artisanal of unskilled employment in agriculture;

iv. Declining employment in agriculture; and

v. Under-employment due to seasonal factors and more labour supply than demand.

Endorsement of New Employment Schemes by NDC and its Subsequent Launching:

The 46th meeting of the National Development Council, held on 18th September, 1993, unanimously endorsed three employment generating schemes, covering the rural poor, educated unemployment and women.

Accordingly in 1993-94, two new programmes were launched in order to give a fillip to employment generation. These two programme included: (i) Employment Assurance Scheme (EAS), and (ii) Prime Minister’s Rozgar Yojana (PMRY) for the Educated and Unemployed youth.

(i) Employment Assurance Scheme (EAS):

The Employment Assurance scheme was introduced on 2nd October, 1993 to make provision for “assured employment” for the rural poor.

The highlights of the scheme are as follows:

(a) Aim:

The scheme (EAS) was implemented in the 3,175 backward blocks with an aim to provide 100 days of unskilled manual work to all those who were eligible in the age group of 18-60 years.

(b) Feature:

The scheme will provide unskilled manual work to rural poor with statutorily fixed minimum wages linked to the quantum of work done. Its funding pattern is 80: 20 by the Centre and the States respectively. The scheme is targeted at the poor especially during the lean agricultural season in rural areas.

The works undertaken are run departmentally and no contractors are hired. Part of the wages may be paid in terms of food grains. The collector of the district is assigned to oversee the performance. Under this scheme, applicants will be given a “family card” listing the number of days of employment under different programmes.

The objective of the scheme (EAS) is to create economic infrastructure and community assets for sustained employment and development. Specific guidelines had been sent by the centre to various states so as to ensure that the provision of employment under the scheme resulted in the creation of durable assets in each block where the scheme had been launched. The implementing agencies were made responsible for the payment of minimum wages according to the standard of performance under the scheme.

A part of the wages were paid in the form of food grains not exceeding 50 per cent of the wages in cost. However, the payment of wages in terms of food grains has been made optional, depending upon the price of food grains in the open market.

Achievement:

During the first year since introduction, i.e., during 1993-94 more than 49.5 million man- days of employment has been generated and nearly 1.7 million have been registered under the newly launched Employment Assurance Scheme (EAS).

The states where maximum number of man day of employment generated include Andhra Pradesh followed by Madhya Pradesh, Orissa and West Bengal. During the first eight months of 1994-95 about 115 million man-days of employment was generated under the EAS scheme.

Among these states, about 2.9 million man-days of employment had been generated in Andhra Pradesh while the figure touched about 2.3 million in Madhya Pradesh. In Orissa, nearly 1.5 million man-days of employment was generated and the figure was almost the same in the case of West Bengal.

In 2003-04, total man-days of employment generated under EAS was around at 37.28 crore. At the end of 2003-2004. EAS had generated total employment to the extent of 302.25 crore man-days, since its inception in October 1993.

(ii) Mahila Samridhi Yojana (MSY):

The Mahila Samridhi Yojana was also launched on 2nd October, 1993 in order to benefit all rural adult women. This scheme entitles every adult women who opens an MSY account with Rs 300 to get an incentive of Rs 75 for a year.

The MSY is aimed at empowering rural women with greater control over household resources and savings. It is now implemented through post offices. At the end of October 1995, a total of 1,25,423 accounts had been opened under the scheme.

(iii) Prime Minister’s Rozgar Yojana (PMRY):

On 2nd October, 1993, the Government introduced another new employment oriented scheme—Prime Minister’s Rozgar Yojana (PMRY) under the on-going Eighth Plan. The scheme is specially designed for educated unemployed youth which will provide employment to more than one million persons by setting up seven lakh micro enterprises during the Eighth Five Year Plan in industry, service and business.

The scheme initially covered urban areas only during the 1993-94, subsequently covered both the urban and rural areas. The scheme but involved an expenditure of ? 540 crore to meet the capital subsidy, training and administrative cost during the remaining period of the Eighth Five Year Plan.

The scheme provided a loan, up to a ceiling of Rs 1 lakh in case of individuals. If two or more eligible persons enter into a partnership, projects with higher cost can be assisted provided the share of each person in the project cost did not exceed Rs 1 lakh.

An entrepreneur is required to contribute 5 per cent of the project cost as margin money in cash. Subsidy at the rate of 15 per cent of the project cost subject to a ceiling of Rs 7,500 per entrepreneur was provided by Central Government. All those who undertook Government sponsored technical course for a minimum duration of six months besides matriculate and ITI diploma holders were be eligible for the scheme.

Under the PMRY, unemployed educated youth between the 18-25 years age group and of families with annual income up to Rs 24,000 along with certain educational and other criteria were eligible for such assistance.

In 2003-04, total micro enterprises developed under PMRY was 1.2 lakh and total employment generated was 1.8 lakh. At the end of 2003-2004 PMRY has developed micro enterprises to the extent of 17.2 lakh and generated employment to the extent of 24.82 lakh since its inception in October 1993. Under PMRY, the Government assisted 20 lakh youth for self-employment during the Tenth Plan.

(iv) JRY:

Moreover, the achievement of JRY in respect of employment generation was 782 million man- days in 1992-93 and 1,026 million man-days in 1993-94. The 1994-95 budget provide for Rs 70.1 billion and set a target of employment generation at 980 million man-days, against which the achievement of JRY in 1994-95 was 952 million man-days.

In 1998-99, the target of employment generation under JRY is fixed at 396.6 million man-days but during 1998-99, the achievement was 375.2 million man-days. Under JRY, about 50 per cent employment generation during 1998-99 came from SC/ST group.

(v) Nehru Rozgar Yojana (NRY):

Nehru Rozgar Yojana (NRY) contemplated by the Ministry of Urban Affairs was designed to create employment opportunities for urban poor. This programme was launched in October 1989 with the objective of providing employment opportunities to the unemployed and under employed urban poor.

The Yojana is applicable to household living below the poverty line in urban slums and within this broad category, SC/ST and women constitute a special target group.

Nehru Rozgar Yojana consists of three sub schemes:

(a) Scheme of Urban Micro enterprises. (SUME),

(b) Scheme of Urban Wage employment (SUWE) and

(c) Scheme of Housing and Shelter Upgradation (SHASU).

So far, 6.55 lakh beneficiaries have been assisted in setting up of micro enterprises under SUME. About 541.52 lakh man-days of work have been generated through the construction of economically and socially useful public assets under SUWE and SHASU till 1994-95. Under NRY, total number of families assisted was 2.37 lakh in 1992-93, 1.52 lakh in 1993-94, 1.25 lakh in 1994-95 and 0.6 lakh during 1997-98 as against the target of 1.2 lakh.

Total man-days of employment generated under NRY was 140.5 lakh in 1992- 93, 123.7 lakh in 1993-94, 92.9 lakh in 1995-96 and 44.6 lakh during 1997-98 as against target of 135.8 lakh. In December, 1997, this programme was amalgamated with SJSRY.

(vi) Prime Minister’s Integrated Urban Poverty Eradication Programme (PMIUPEP):

The Prime Minister’s Integrated Urban Poverty Eradication Programme (PMIUPEP) was launched in 1995-96 with a specific objective of effective achievement of social sector goals, community empowerment, employment generation and skill upgradation, shelter upgradation and environmental improvement with a multi-pronged and long-term strategy.

The Programme covered 5 million urban poor living in 345 class II Urban Agglomerations (towns) with a population of 50,000 to 1,00,000 each. There was a provision for Rs 800 crore as central share for the entire programme period of 5 years. In 1995-96, Rs 100 crore were allocated for the programme.

The programme benefitted about 150 lakh urban poor in 1996-97. As on October 1996, over 14,000 and 1,00,000 beneficiaries had been identified for self-employment and shelter upgradation respectively. In December 1997, this programme was amalgamated with SJSRY.

(vii) The Swarna Jayanti Shahari Rozgar Yojana (SJSRY)/National Urban Livelihoods Mission (NULM):

The Swarna Jayanti Shahari Rozgar Yojana (SJSRY) which subsumed the earlier three urban poverty programme viz., Nehru Rozgar Yojana (NRY), Urban Basic Services for the poor (UBSP) and Prime Minister’s Integrated Urban Poverty Alleviation Programme (PMIUPEP) came into operation from December 1997.

This programme sought to provide employment to the urban unemployed or underemployed poor living below poverty line and educated up to XI standard through encouraging the setting up of self-employment ventures or provision of wage employment.

The scheme gives special impetus to empower as well as uplift the poor women and launches a special programme, namely, Development of women and children in Urban Areas (DWCUA) under which groups of urban poor women setting up self-employment ventures are eligible for subsidy up to 50 per cent of the project cost.

An allocation of Rs a 181.0 crore was provided in 1999-2000 (BE). In 1998-99, the DWCUA scheme had assisted 0.01 lakh women related to their self-employment schemes. During 2001-02, Rs 168 crore was allocated against which’ Rs 45.50 crore was spent. In 2002-03, all allocation of Rs 105 crore was provided against which Rs 74.0 crore was spent.

Two special schemes of SJSRY include—the Urban Self-Employment Programme (USEP) and the Urban Wage Employment Programme (UWEP). SJSRY is funded on a 75: 25 basis between Centre and States. During 1997-98, 1998-99 and 1999-2000, a sum of Rs 102.51 crore, Rs 162.28 crore and Rs 123.07 crore respectively were spent in the States and Union Territories under different components of SJSRY.

About the performance of SJSRY, total number of beneficiaries under USEP was 0.04 million in 1998-99 and 0.10 million in 2003-2004 and total number of persons trained under USEP was 0.05 million in 1998- 99 and 0.12 million in 2003-2004. Again, total man-days of employment generated under UWEP was 6.60 million in 1998-99 and 10.14 million in 1999-2000 and 4.56 million in 2003-04.

The number of urban poor assisted for setting up micro/group enterprises in 2005-06 was 0.9 lakh against a target of 0.80 lakh. The number of urban poor imparted skill training in 2005-06 was 1.42 lakh against a target of 1.0 lakh.

Budget allocation for the SJSRY scheme for 2011-12 is Rs 813.0 crore of which Rs 676.80 crore had been utilized till February 16, 2012. During 2009-10, as reported by States/UTs, a total of 28,613 urban poor have been assisted in setting up individual enterprises, 13,453 urban poor women have been assisted in setting up group enterprises and 27,463 urban poor women have been assisted through a revolving fund for thrift and credit activities and also 85,185 urban poor have been imparted skill training. A total of 3,63,794 beneficiaries have been assisted in the year 2011-12.

NULM:

SJSRY was replaced by the NULM in September 2013. It aims to provide gainful employment to urban employed and under employed. The NULM will focus on organizing urban poor in SHGs, creating opportunities for skill development leading to market based employment, and helping them to set up self- employment ventures by ensuring easy access to credit.