Measurement of Unemployment in India: Dantwala Committee Approach:

Let us now first discuss the approaches to measure open unemployment and underemployment in India.

On the basis of time and willingness criteria open unemployment and underemployment have been estimated using the following three approaches which were recommended by an expert committee headed by Prof. M L. Dantwala:

(i) Usual Status Approach:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This approach records only those persons as unemployed who had no gainful work for a major time during the 365 days preceding the date of survey and are seeking or are available for work. Thus, the estimates of unemployment obtained on the basis of usual status approach are expected to capture long-term open unemployment.

(ii) Weekly Status Approach:

In this approach current activity status relating to the week preceding the date of survey is recorded and those persons are classified as unemployed who did not have gainful work even for an hour on any day in the preceding week and were seeking or were available for work.

The persons who may be employed on usual status approach may however become intermittently unemployed during some seasons or parts of the year. Thus, unlike the usual status approach, weekly status approach would capture not only open chronic unemployment but also seasonal unemployment. Besides, this approach provides weekly average rate of unemployment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(iii) Daily Status Approach:

The weekly status approach records a person employed even if he works only for an hour on any day of the whole week. It is thus clear that the weekly status approach would tend to underestimate unemployment in the economy because it does not appear to be proper to treat all those who have been unemployed for the whole week except an hour as employed.

Indeed, the demand for labour in farming and non-fanning households often fluctuates over a small period within a week. Hence the need for the use of daily status approach to measure the magnitude of unemployment and underemployment in India.

In the daily status approach current activity status of a person with regard to whether employed or unemployed or outside labour force is recorded for each day in reference week. Further, for estimating employment and unemployment, half-day has been adopted as a unit of measurement.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A person who works for 4 hours or more up to 8 hours on a day is recorded as employed for the full day and one who works for an hour or more but less than 4 hours on a day is recorded as employed for half-day. Accordingly, persons having no gainful work even for one hour on a day are described as unemployed for full day provided that they are either seeking or are available for work.

Thus, the daily status approach would capture not only the unemployed days of those persons who are usually unemployed but also the unemployed days of those who are recorded as employed on weekly status basis.

Hence daily status concept of unemployment is more inclusive than those of usual status and weekly status approaches and would yield an average number of unemployed person-days per day in the year indicating the magnitude of both open unemployment and underemployment. They are also referred to as person-years unemployed so as to distinguish them from persons unemployed.

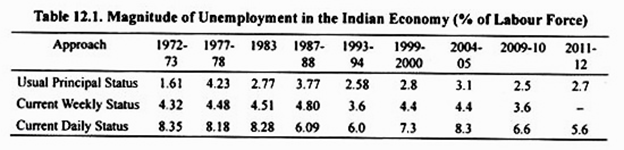

The estimates of unemployment on the basis of above three approaches are presented in Table 12.1. It may be observed from this table that according to NSS 1999-2000 round, 2.8 per cent of labour force were unemployed on usual status basis and 4.4 per cent of labour force were unemployed on weekly status basis and 7.3 per cent of labour force on current daily status (CDS) basis.

In 2004-05 (60th Round) unemployment rate further increased. On current weekly status basis, unemployment rate went up to 4.6 per cent in the rural areas and 6.4 per cent in the urban areas and 3.08 for India as a whole. On current daily status basis, in 2004-05 rate of unemployment rose to 8.2 per cent in rural areas and to 8.3 per cent in the urban areas and 8.2 per cent in case of All India.

In absolute numbers, Planning Commission estimated unemployment to be of the order of 35 million persons on current daily status basis in April 2002 in the beginning of the ,10th Plan. On the basis of 60th round, number of persons unemployed on the current daily status basis rose to 34.7 millions in 2004-05 till 2004-2005.

However, according to 66th round of National Sample Survey (NSS) for the year 2009-2010, current daily status (CDS) unemployment rate as per cent of labour declined to 6.8 in rural areas and to 5.8 in urban areas giving us unemployment rate as 6.6% of labour force for whole India.

However, in our view this is the result of special employment guarantee scheme, MGNREGA, started in 2007-08 under which people are employed in more construction activities for a short period of time and does not represent the stable growth of employment opportunities.

As compared to 1993-94, all rates of unemployment (usual status, weekly status and daily status) increased in 2004-05. This clearly shows that economic reforms initiated since 1991 led to the worsening of unemployment situation in the Indian economy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Note that, contrary to what could be expected, weekly status unemployment is not much greater than that of the usual status approach. This is for two reasons. First, a person to be identified as unemployed on weekly status approach has to pass through a severe test, namely, he did not work even for only an hour in the whole reference week.

Now, in an economy where there is predominance of self-employed households engaged in family-based enterprises, it is quite easy for a person to have worked for an hour in a week even during the lean periods of the year and therefore get registered as employed rather than unemployed. Secondly, during the slack seasons of the year some persons, mainly women, withdraw themselves from the workforce.

Therefore, instead of being counted as unemployed, they are treated as ‘outside labour force’, for they generally report as ‘not available for work’. As a result, whereas weekly status employment estimates are relatively greater than that of usual status, their unemployment estimates are not much higher.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Further, it is noteworthy that both the usual and weekly status approaches reveal a rather small magnitude of surplus labour. This is because both these approaches measure open unemployment in the country. However, in India with predominance of self-employed households and absence of social security system to support the people, they can hardly afford to remain absolutely unemployed.

The new hands that are added to the labour force every year as a result of increasing population do not remain openly unemployed; they share employment and work with others so that there is more of underemployment and disguised unemployment rather than open unemployment.

Thus, quite expectedly, the daily status approach which seeks to capture both open unemployment and underemployment reveals that quite a large magnitude of surplus labour exists in India.

It will be seen from Table 12.1 that around 9 per cent of labour force were found unemployed in 2004 on daily status basis. It has been estimated that the magnitude of daily status unemployment increased to about 40 million person-years in April 2004.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, even the daily status approach does not fully measure the magnitude of surplus labour in the Indian economy. Evidently, this also would have a tendency to under-record unemployment as it considered a person working for only 4 hours (1/2 of the standard day) as fully employed and a person who worked for an hour (1/8th of the standard day) as employed for half-day. In fact, as an alternative, hourly status approach measuring employment and unemployment in terms of manhours would be probably more appropriate.

Further, the daily status approach (or even the alternative hourly approach), like the usual and weekly status approach, cannot fully capture disguised unemployment of those persons whose intensity of work and consequently productivity is very low even though they are employed for a long time.

In India, as in other labour-surplus developing countries, people are generally found to be working longer hours and larger number of days than one is really required to do the given work by stretching or spreading the work. Therefore, for the proper assessment of the magnitude of surplus labour that currently exists in the Indian economy, unemployment on the basis of daily/hourly status ought to be supplemented by a measure of disguised unemployment based on a norm of productivity or work intensity.

Despite the above limitations it is clear that daily status unemployment is a relatively better measure of the magnitude of surplus labour as it covers open unemployment as well as a good amount of underemployment.

A good number of unemployment in a labour-surplus country such as India manifests itself in the form of disguised unemployment, especially in the agricultural sector. It is a common knowledge that with minor changes in organisation and with the existing techniques, our agriculture can be looked after by a much smaller number of workers and they can be withdrawn from agriculture without reduction of agricultural output if alternative employment opportunities are available.

Since employment opportunities in the non-agricultural sector have not been growing rapidly, the new entrants to the workforce are compelled to remain in agriculture and perpetuate the phenomenon of disguised unemployment which means that people are engaged in occupations where their marginal productivity is zero (if not negative) and that a shift to alternative occupations will improve their marginal productivity and add to national income of the country.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The basic solution to the problem of this sort is the faster rate of capital formation so as to enlarge employment opportunities. For this purpose, every possible encouragement should be given to savings and their productive utilisation in increasing the rate of investment.

In the developing countries investment incentives for the private sector are very low and the Government can assist in the process of capital formation directly as well as indirectly. Through a fiscal policy which encourages savings and investment and an easy monetary policy it can do much to encourage investors.

The Government itself can participate in the process of capital formation by undertaking such development activities which do not attract the private investors. Therefore, the Government has got to assume a special role in speeding up the rate of economic development.

The other line of attack has got to be on the rate of population growth. If population grows at a rapid rate then, to maintain the people even at their existing levels, large amounts of capital are needed which could otherwise have been used to raise the amount of capital available per man and hence to raise the living standards at a faster rate.

Apart from accumulation of capital (i.e., machines, factory buildings, tools and equipment), we should increase investment in physical infrastructure such as roads, transport, ports, power, highways, irrigation facilities to generate opportunities for productive employment.

Further, by adopting suitable fiscal and monetary policies we should discourage the use of capital-intensive techniques. Lastly, land reforms initiated in the earlier periods of planning should be effectively implemented to ensure access to land for agricultural households.