Marx rejected Malthus’s law of population and explained the determination of wage rate at the minimum subsistence level with the help of his notion of reserve army of labour (that is, unemployed labour force). We will explain this below.

Karl Marx presented his theory of development in his now famous book Das Kapital (1867). There are many similarities between his theory and Ricardo’s theory of development but he drew quite different implications. Basic similarity between Marx and Classicals (including Ricardo) is that capital accumulation is prime mover of economic growth. The other basic assumption of Marx and Ricardo is that supply curve of labour to the modern industrial sector is perfectly elastic at the minimum subsistence level. However, the reason given for the determination of wages at the subsistence level is quite different.

White Ricardo believed in the Malthusian Law of Population to assume that wage rate will remain stable at minimum subsistence level; if as a result of development, wage rate rises above minimum subsistence level, population will increase bringing down the wage rate to the minimum subsistence level. On the other hand, wage rate cannot go below the minimum subsistence level as workers would not survive at that level which will lower the population growth rate causing wage rate to rise to the minimum subsistence level.

Why do Wages Remain at the Subsistence Level– Marxist View:

According to Marx, the forces at work in a capitalist economic system bring about the increase in the rate of exploitation of labour. The basic force at work is the competition among the capitalists to the increase in the rate of surplus value what Marx called rate of exploitation and thereby enlarge their profits share relative to wages share.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Now the question is how the capitalists are able to do this. First thing to understand in this connection is that Marx, like Ricardo, believed that the market wage rate tended to be equal to the minimum subsistence level in the long run. In other words, wage rate, according to Marx, cannot rise above the subsistence level except in the very short run.

However, reason given by Marx for the existence of the minimum subsistence wages is different from what Ricardo thought it to be. According to Ricardo, it was the increase in population above the subsistence level that kept the wages tied to the minimum subsistence level. In Marx,’s analysis, it is the prevailing excess of labour supply over the demand for labour that prevents the wages from rising above the minimum subsistence level. Because of the continuous increase in labour supply over demand, there comes to exist a large amount of unemployed workers which Marx called “the reserve army of labour.” It is therefore the existence of reserve army of labour (i.e., the unemployed) that prevents the wages from going above the minimum subsistence level.

Now, why does supply of labour remain excess relative to demand for it. Marx assumed that as capitalist enterprise progresses at the expense of pre-capitalistic enterprise more labourers are released through the disappearance of the handicraft units than are absorbed in the capitalist sector owing to the difference in productivity per head between the two sectors. As long as the growth of capitalist enterprise is at the cost of shrinkage of pre-capitalist enterprise the increase in the supply of wage-labour tends to run ahead of-the increase in the demand for wage labour. Thus, as long as the reserve army of labour exists wage rate in the industrial sector will be prevented from rising above the subsistence level.

Concept of Marx’s Theory of Surplus Value:

Marx’s concept of surplus value plays an important role in his theory of capitalist development. It is therefore proper for us to explain his concept of surplus value and how it is related to profits earned by the capitalist-entrepreneur and exploitation of the workers which leads to the class struggle in the economy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The Marxian analysis of capitalism rests on the labour theory of value, which Marx took over from Adam Smith and Ricardo. According to Marx’s labour theory of value, the value of a commodity is determined by the labour time necessary for its production. It is the labour alone that is the ultimate source of all value. According to Marx, equipment and raw materials do not create value – they merely transfer their own value to the value of the final product.

On the other hand, labour creates more value than the value of labour power expended on the production of goods and services. In other words, it is the unique characteristic of labour power that it creates more value than its own value. The value of labour power is determined by the cost of reproduction of labour, that is, by the value of goods and services that are required to maintain the labourers at the minimum subsistence level. In other words, the value of labour power, that is, the own cost of labour, means the minimum subsistence wages which are just sufficient to keep the labourers living and intact.

Labour theory of value and the concept of value of labour power as being equal to the minimum subsistence level are crucial in Marxian theory because they form the basis of Marx’s theory of surplus value which in turn explains the distribution of aggregate income into wages and profits in a capitalist economy.

Since labour creates more value product than its own cost or value of labour power, that is, more than the minimum subsistence output, the surplus emerges which is expropriated by the capitalists who happen to own the material means of production such as capital equipment, land and raw materials with which labour is employed to produce goods and services. This surplus value represents profits of the capitalists. According to Marx, the surplus value or profits which are created by labour over and above the value of their subsistence requirements are unjustifiably expropriated by the capitalist class. In other words, the surplus value or profits extracted from labour by the capitalists represents the exploitation of labour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is through the ownership of material means of production that the capitalists are able to exploit the labour class and extract surplus value from it. Thus the share of profits in the total value of output depends upon the magnitude of surplus value extracted from it. Prof. Patterson rightly remarks, “The notion of surplus value is crucial to the Marxian theory of income distribution; surplus value is the source of profits and thus the amount of surplus that can be expropriated by the capitalist class will determine the relative share of profits in the income total.”

In the Marxian analysis, the total value of output is composed of three elements. Firstly, it consists of the value of the capital and raw materials consumed in the production of goods and services. Marx calls this as constant capital which is written as C. Secondly, the total value of output contains the value of labour power used in the production of goods and services, that is, total wages in terms of minimum subsistence wages paid to the workers. Marx calls this as variable capital which is written as V. Thirdly, the total value of output contains the surplus value which is created by the labourers over and above the value of their labour power and which, as seen above, is bagged by the capitalist class as profits.

Thus –

Total value output = constant capital + variable capital + surplus value

= C+V+S

C, as said above, stands for capital consumption. It should be noted that in case of the whole economy C will contain only the consumption of fixed capital, since raw materials are intermediate products and their value will be included in the value of final goods produced. If we subtract the value of C from the total output, we get the net output which will consist of value of the labour power or variable capital (V) and the surplus value (S). V and S are wages share and profits share respectively in the net output. Thus –

Net output = V+S

If Y stands for net national output, then

Y= V+S

ADVERTISEMENTS:

or Surplus value, (S) = Y— V

That is, surplus value (S) is equal to net national income minus the variable capital (i.e., wages).

The rate of surplus value or what Marx called ‘degree of exploitation’ is given by the ratio S/V

It is this rate of surplus value S/V which represents the ratio of profits share to the wages share in the national income. A rise in this ratio means the increase in the rate of exploitation and hence increases in the profits share relative to wages share in the national income.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

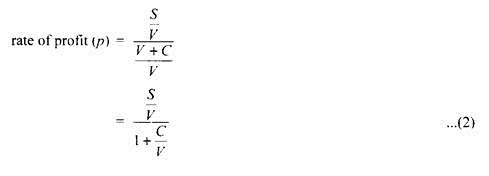

However, the rate of profit in Marx’s theory is given by the ratio of surplus value (S) to the total capital, that is, variable capital (V) + constant capital (C). Thus rate of profit (p) is given by-

We further elaborate it by dividing the denominator in equation (1) by variable capital, V. In doing so we have-

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Where, C/V, that is, ratio of constant capital to the variable capital was called by Marx as ‘organic composition of capital’ which in modern terminology is called capital-labour ratio or simply capital intensity. From equation (2) above it follows that with economic development as technology becomes more capital-intensive, the organic composition of capital (that is, capital-labour ratio) C/Y rises through time and rate of profit (p) falls unless rate of surplus value S/V rises.

However, Marx expected that rate of profit can be kept high by increasing the surplus value. Only when a large accumulation of capital has taken place and as a consequence reserve army of labour is exhausted, wages will go up resulting in decline in profit. Even then the capitalists try to keep wages down by substituting more capital for labour. This will, on the one hand, lead to the ‘immiseration of workers’ causing social upheaval and on the other hand, would raise the ‘organic composition of capital’ (C/V) which will lower the ratio of profit.

Capital Accumulation, Technological Progress and Economic Growth:

Unlike other classical economists Marx considered technological change rather than profits as the primer driver of economic growth in capitalist economies. According to him, technological changes in each stage of a country’s economic development determine not only the economic situation, but also the production relations in a society. Thus, according to him, the hand mill created the feudal landlord and steam mill the capitalist.

Marx explained his theory of development with his assumption that labour supply is perfectly elastic at the subsistence wages. The capitalist engages workers for the production of goods and these workers create surplus value which is reinvested to increase capital accumulation. But Marx believed that capital accumulation along with technological progress increases labour productivity and brings about economic growth.

But Marx regarded technological progress as being labour-saving and capital-using. At the time of writing Das Kapital, technological change dominated the capital- intensive innovations such as steamship, machines run by diesel engine, railroads, and heavy chemicals.

Thus, according to Marx, with further economic development there was tendency for capital per worker to rise. With wages remaining sticky at subsistence level, the more surplus value is created by workers which are invested in new capital goods.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The growth of factory system of industrial production with the establishment of capitalist mode of production brought about the destruction of handicrafts, that is, the simple commodity production by craftsmen and artisans. This is because the craftsmen could not compete with the goods produced with the aid of machines. This led to the decline of simple commodity production of handicrafts by craftsmen. With the destruction of handicrafts, capitalist mode of production became the dominant mode of production.

The change from small-scale production of handicrafts by craftsmen to large-scale industrial production with the aid of machines in a factory system was, without doubt, a big stride forward in the development of the productive forces. Machines proved to be powerful means by which man could tame the forces of nature. Machines also lightened labour of workers and considerably raised their productivity.

With further inventions and development of science and technology, the machines became bigger and more sophisticated. The exploitation of the workers and plunder of colonies by the capitalist class and consequently concentration of wealth in its hand enabled this class to invest more and more in machines and factories. This ensured a higher rate of capital formation and industrial growth in the Western European countries.

It is worthwhile to note that at that time the propensity of the capitalist class was not so much ‘to consume’ but ‘to accumulate’. The function of the capitalist, according to Marx, is to ‘accumulate and it is primarily because capitalist system offered stimulus to accumulation of capital that Marx recognized the historical role performed by it in the development of the Western economies. Having high propensity to save the capitalist class invested the surplus value extracted from the workers. ‘To accumulate’ was passion with the capitalists in the earlier phases of capitalism. This generated a higher rate of capital formation and consequently of economic growth.

To quote Marx, “Frantically bent upon the expansion of value, he (the capitalist) relentlessly drives human beings to production for production’s sake, thus bringing about a development of social productivity and the creation of those material conditions of production which can alone form the real basis of a higher type of society… only as the personification of capital is the capitalist respectable.” Consequently, rapid accumulation of capital brought about unprecedented economic growth in the Western countries. It is because of economic growth achieved under capitalism that Western European countries and the U.S. have become affluent nations today.

Rising Exploitation of Labour with Capitalist Development:

Now, the wages being fixed at the minimum subsistence level, the measures which bring about the increase in the output of labour will raise the rate of exploitation and therefore the profits of the capitalists. According to Marx, the capitalists who own the material means of production compete with each other to increase the rate of exploitation (S/V) which is the same thing as the increase in profits share relative to wages share. Thus, Professor Patterson remarks. “In the Marxian theory competition takes the form of a struggle among the owners of the material instruments of production to increase the rate of exploitation or, and this comes to the same thing, the non-wage share in the income total.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Now, there are three ways of increasing the surplus value or rate of exploitation. In the first place, this can be done by lengthening the working day. When the workers are forced to work for a larger number of hours in a day than before, the total output increases and, given the wages paid to them, the surplus value expropriated by the capitalists and therefore the rate of exploitation increases. Secondly, the surplus value or rate of exploitation may be raised by increasing the intensity of labour that is, forcing the workers to do greater amount of work while keeping the working day constant.

However, the extent to which the surplus value can be increased in these two ways is very limited. The third and, according to Marx, a major way in which the capitalist can increase the surplus value is raising the physical productivity of workers through technical progress. Technical progress involves the improvement in techniques of production. Workers working with better and improved techniques produce more than before while working the same number of hours in a day and with same intensity and as a result the total output produced by them increases. With wages remaining constant at the minimum subsistence level, the difference between total output and the subsistence output as a result of technical progress increases and hence the surplus value or rate of exploitation rises.

Technological Progress and Capital Accumulation:

But technical progress can be achieved only if there is capital accumulation. As a result, the competition among the capitalists seeking to increase the surplus value forces them to accumulate capital, that is, to make investment. But in the Marxian scheme, as has been pointed out by Kaldor, capital accumulation or investment activity is not motivated by the lure of profit, but it is the necessity forced on them by the competitive struggle among the capitalists.

We thus see that as technical progress and capital accumulation proceed apace and capitalist economic system develops, the surplus value extracted from the workers or rate of their exploitation will increase as a result of the competitive struggle among the capitalists. Consequently, with the development of capitalist economic system, the relative share of wages (labour’s share) in the national income will fall and the relative share of profits (capitalist’s share) will rise.

Therefore, the development of the capitalist economy involves the steady worsening of the living conditions of the working classes. This has been called by Marx as “the immiseration of the proletariat” or “the law of increasing misery of the working classes.” According to this law, technical progress and capital accumulation in a capitalist society and consequently the growth in the national income must lead to the fall in the relative share of wages in the national income and the rise in the relative share of profits.

It is thus clear that about the changes in the relative share with development of the capitalist system Marx reaches a conclusion which is diametrically opposed to the conclusion of Ricardo who thought that with the development of the capitalist economy, relative share of wages will increase and the relative share of profits will decline. Professor Patterson rightly points out that in the Marxian macroeconomic model of income distribution “the fundamental cause of decline in the relative share of wages is technical progress, the fruits of which entirely go to the owners of the physical instruments of production. The alleged increasing misery of the working class does not come from any decline in the level of real wages, since their ‘misery’ does not increase in any absolute sense; it is the result instead of the failure of real wages to advance along with gains in productivity. This is the heart of Marx’s theory of distribution.”

Graphical Illustration of Marxian Model of Development:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

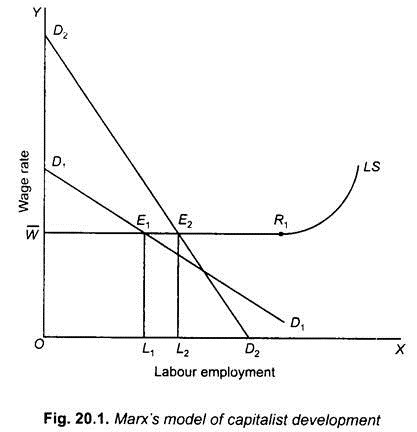

Marxian model of economic development is illustrated in Fig. 20.1 through demand and supply curves of modern economics. It represents the labour-market in the modern capitalist sector. Note that demand curve of labour represents marginal product (MP) of labour as more labour is employed. In Fig. 20.1, the vertical axis represents the wage rate in the modern capitalist sector. W̅ represents the subsistence level of wages and as per Marx’s theory labour-supply curve LS is perfectly elastic at this subsistence wage level W̅ over a long range of expansion in labour employment.

With a given initial stock of capital (K1), labour demand curve is given by D1D1, which cuts labour-supply curve LS at point E1 and determines OL1 level of labour employment at the subsistence wage level W̅, . If W̅R1 represents the number of workers seeking employment at the subsistence wage W̅, then out of this, with the given initial capital stock and demand for labour D1D1, W̅E1 (= OL1) will be employed and E1R1 will constitute reserve army of labour (i.e., unemployed workers).

The area OL1E1 W̅ is total wages earned by workers where W̅ E1D1 represents the surplus value extracted by the capitalists from workers. This surplus value will be reinvested. This will promote capital accumulation over time. However, Marxian theory of capital accumulation is not of the type of capital widening in which investment is made in the same type of capital goods. In his theory technological progress takes place along with capital accumulation and the new capital goods or machines in which investment is made embody new and more productive labour-saving technology.

As a result, labour employment grows much slowly than growth of output. In Fig. 20.1 the effect of labour-saving bias of new technology embodied in the new machines or capital goods is represented by the change in labour demand curve to a steeper curve D2D2 which cuts the initial labour demand curve D1D1from above at point E2 and determines labour employment equal to OL2. Thus with the use of new capital goods embodying new labour-saving technology while there is a large increase in output from OL1E1D1, (=Σ MPs.) with labour employment OL1 to the output OL2 E2D2 with labour employment OL2. On comparing we find that the increase in labour employment is much less than the growth in output.

Thus wage remaining fixed at the subsistence level W̅, the capital accumulation embodying labour-saving new and improved technology would create higher surplus value for further investment and growth. Besides, use of labour-saving technology will create unemployment while labour force is growing. As a result, according to Marx, reserve army of labour will never be exhausted. Thus Yujiro Hayami and Yoshisa Godo, “Marx envisioned that, with the ability of the modern capitalist productive system to ruin traditional self-employed producers together with the labour-saving bias in industrial technology, the industrial reserve army will never be exhausted, high rates of profit and capital accumulation in the capitalist economy are guaranteed by maintenance of low wage rates under the pressure of the ever-existing reserve army.”

The process of capitalist development with rapid capital accumulation and use of labour-saving technology necessarily involves rapid increase in income inequalities as in his model wages remain at the subsistence level and technological unemployment prevails on a large scale due to slow growth of employment opportunities. These increasing inequalities will create conflict between the working class and capitalist class. These will, according to Marx, lead to violent revolution in which capitalism will be eliminated and in its place socialism based on public ownership of property will come into existence.

Inner Contradictions of Capitalism and Its Collapse:

Class Struggle and Increasing Misery of the Workers:

Though capitalism brings about unprecedented riches and affluence to the Western countries, it also contains, according to Marx, inner contradictions which would ultimately cause its collapse. It is due to the basic inner contradictions that class struggle becomes more intense with the development of capitalist mode of production. Capitalist mode of production, according to Marx, is based upon the exploitation of the working class. As a result, under capitalism there is a clash of interests between the ‘haves’—the capitalists— and the ‘have-nots’—the proletariat.

This gives rise to class struggle between the two. In order to compete successfully with each other, each capitalist tries to raise the surplus value and the rate of exploitation of the workers. He tries to do this by lowering the real wages, increasing the working hours and increasing the intensity of work by the workers. This makes the life of the workers quite miserable. The increasing misery of the working classes will prompt them to revolt against the capitalist system and ultimately overthrow it through revolution.

Emergence of Under-Consumption, that is, Over-Production:

Another related form of inner contradictions exists in the capitalist mode of production which also causes its downfall. This form of contradiction leads to under-consumption or what is also called over-production, that is, lack of demand for goods which, according to Marx, causes periodic depressions and economic crises. In order to increase the surplus value, capitalists introduce new machines embodying higher technology.

This raises, in Marxian terms, the organic composition of capital, which in modern terminology means capital-labour ratio. The rise in capital-labour ratio and the technological displacement of labour in handicrafts as a result of the use of technically superior new machines causes the reserve army of unemployed to increase. This mounting unemployment of labour also enables the capitalists to keep the wages of labour at the bare subsistence level and appropriates all gains in labour productivity.

The low level of employment as well as low wages of labour creates meagre incomes or purchasing power for the workers who constitute a majority in the society. This creates the problem of lack of effective demand for goods or what is called by Marx as under –consumption. As a result, the goods produced on a mass scale by the capitalists cannot be sold. This results in depression or economic crisis. According to Marx, as the capitalist system gains maturity, these depressions or economic crises will go on increasing in intensity and will ultimately bring about its collapse.

Cut-Throat Competition:

It follows from above that Marx attempts to explain how capitalism itself will generate conditions which will bring about its end and replace it by socialism. For a time, he says, capitalism will flourish. The capitalists will become richer and richer, but will at the same time become fewer and fewer, the bigger whale swallowing up the smaller fish on account of the cut-throat competition among them; Production will expand resulting in scramble for markets abroad. This will lead to imperialist wars, one war followed by another and more terrible than the preceding one till capitalism perishes in the conflict through workers overthrowing the system through revolution.

Thus, the law of capitalistic production itself will result in expropriation of the capitalists when capital is centralised. “Along with the constantly diminishing number of the capitalists who usurp and monopolise all gains in production, grows the mass of misery and exploitation of working classes. But with this grows the revolt of the working class, a class which will increase in numbers.

The time will come when the monopoly of capital will become a fetter upon the capitalist mode of production. Then the knell of capitalist private property will sound. The expropriators will be expropriated. Colonialism and imperialism can lend only temporary respite by supplying cheap raw materials and market for the manufactured goods. But they will also give rise to colonial and imperialist wars resulting in mutual destruction of the capitalist powers.

Thus, according to Marx, capitalism will collapse on account of the growing conflict between labour and capital. Then a new economic and social order represented by socialism will be established, in which private property will disappear and the State will wither away.

Falling Rate of Profit and Collapse of Capitalism:

Although Marx concluded that the relative share of profits will increase with the development of capitalistic economic system as a result of technical progress and capital accumulation, he, however, following Ricardo, took the view that with capital accumulation the rate of profit will be falling. It should therefore be carefully noted that in view of Marx, whereas relative share of profits increases, the rate of profit declines as the capitalist economy develops.

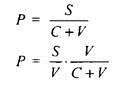

This looks like a contradiction but Marx proved their co-existence. But unlike Ricardo, Marx did not explain the falling rate of profit on the basis of operation of diminishing returns. He explained this tendency of declining rate of profit on the basis of the increase in what he called the “organic composition of capital”. Organic composition of capital is the ratio of constant capital (C) to the total capital (C + V). Thus organic composition of capital is C/(C+V). Now, the rate of profit is equal to the ratio of surplus value (S) to the total capital (C+V) employed, that is, rate of profit is equal to S/(C+V).

Let P stand for the rate of profit. We then have the following relationship –

V/ (C+V) is the ratio of variable capital to the total capital. If we subtract C/(C+V) from 1, we will get the ratio of variable capital to the total capital [or V/(C+V)]. Therefore –

Where, C/(C+V) is organic composition of capital.

From the above equation it follows that if the S/V (the rate of exploitation) remains constant, the, i.e., rate of profit will decline C/(C+V) if, i.e., organic composition of capital increases. Thus while holding that relative share of profits will increase, Marx also took the stand that the rate of profit will decline in the capitalist economy as a result of capital accumulation and consequent increase in the organic composition of capital. In the modern terminology we can say that Marx was of the view that as more capital is accumulated and capital-output ratio rises in the productive processes or, in other words, as more capital-intensive production techniques are employed, the rate of profit will fall.

Critical Evaluation of the Marxian Analysis of Capitalism:

Marxian theory has been criticised on several grounds. Marx has proved to be a bad prophet. Predictions which he made on the basis of his theory have not come true and the actual events have not taken the Marxian line. Marx had predicted that relative share of wages in the national income would fall and the economic conditions of the workers would deteriorate. All this has not come true.

Empirical research has found that share of wages in the national income has remained constant in the Western capitalist countries instead of falling as predicted by Marx. The workers have obtained a due share from the increases in physical productivities brought about by the technical progress and capital accumulation in the capitalist countries. As a result, in absolute terms the living conditions of the workers have greatly improved so that they have now become less revolutionary.

Besides, there has not been found any tendency for the falling rate of profit. On the basis of the falling rate of profit and the concentration of purchasing power in the hands of the few, Marx predicted that the capitalist economies would have periodic crises and ultimately the system would collapse. Actual events have falsified this gloomy forecast of Marx. Of course, there have been trade cycles in these economies but in spite of these short-run fluctuations capitalist economies have made phenomenal progress in the last 200 years or so, so that they have now become affluent countries. Prof, Patterson rightly remarks, “Marx thought the capitalistic system would be increasingly wrecked by crises of greater and greater severity until finally it would collapse amid an uprising of the working class that would usher in the era of Communism. Marx proved to be a bad prophet concerning not only the behaviour of the wage share in the national income, but also the long-term development of capitalism.’

Further, there is a great theoretical flaw in Marx’s contention of falling rate of profit with the increase in organic composition of capital. Several authors have pointed out that law of the falling rate of profit cannot really be derived from the law of the increasing organic composition of capital. Since Marx believes that the real wages of the workers remain fixed at the subsistence level, then as a result of increase in organic composition of capital due to capital accumulation and technical progress, the output per head will greatly increase and, given the real wages constant at the subsistence level, the surplus value (i.e., the profits) earned by the capitalists will greatly increase and will secure a rising rate of profit.

Lastly, Marx’s theory of income distribution under capitalism is based upon the labour theory of value which is not acceptable to the modern economists. Marx’s analysis of surplus value or exploitation of labour is directly based upon his contention that all value is created by labour and capital merely transfers his own value to the value of the commodity.

Capital adds greatly to the productivity of the process and does create a good deal of value. To deny this is to show one’s prejudice. Therefore, Marx’s thesis that value of a commodity is determined by the necessary labour time required to produce it is quite obsolete and not acceptable to the modern economists. Thus when labour theory of value is wrong, the theory of surplus value and exploitation based upon it falls to the ground.

One of the successful predictions of Marx was that the process of capitalist development leads to the increase in inequalities of income distribution and concentration of wealth in few hands. As seen above, incomes of workers are reduced relative to the profits made by the capitalists by the use of the labour-saving nature of new technology in the modern industrial sector.

This is borne out by the experience of developing countries like India where ever since the initiation of economic reforms based on the Washington Consensus of liberalisation, privatisation and globalisation, income inequalities have greatly raised. Where the rich have become very rich, the reduction in poverty is far less. In developing countries where trade movement is weak, labour is ruthlessly exploited.

Besides, it goes to the credit of Marx by pointing out in his model that capital accumulation and technological improvement are drivers of economic growth. While classical economists emphasised rapid capital accumulation for accelerating economic growth, they underestimated the role of technological progress in sustaining economic growth. Marx, on the other band, laid stress on both capital accumulation and technological progress in determining growth of output.

In fact, as explained above, Marx visualised the accumulation of new capital goods (i.e., machines) embodying new improved technology. This is highly relevant for developing countries which aim at accelerating economic growth. However, for generation of adequate employments opportunities, efforts should be made that the new technology used is labour-using rather than labour-displacing.

Further, Marx’s model gives an important insight into the problem of unemployment faced by developing countries (including India). The developing countries like India have achieved rapid industrial growth through large increase in capital accumulation but growth of labour employment in the modern industrial sector has been very slow while, on the other band, increase in labour force has been high due to rapid population growth.

This can be explained by Marx’s view of the use of labour- saving technological change which lowers the employment potential of capital accumulation. Thus, Hayami and Godo write- “Many developing economies have attempted to achieve rapid development by concentrating investment in the modern industrial sector. In some cases significant success in the growth of industrial production has been recorded. However, increases in employment have typically been much slower than output growth owing to concentration of investment in modern machinery and equipment embodying labour-saving technologies developed in high-income countries. On the other hand, the rate of increase in the labour force has been high under explosive population growth. Where labour absorption in agriculture reaches its saturation point under the rapidly closing land frontiers, labour tends to be pushed from rural to urban areas. The swollen urban population beyond limited employment in the modern industrial sector of high capital intensity has accumulated as lumpen proletariat in urban slums.”

A shortcoming of Marx’s model is that he neglected the possibility of food shortage or lack of wage goods leading to the increase in cost of living of the people causing rise in wage rate. At the higher wage rate demand for labour will decline. Marx’s neglect of food problem or wage goods availability has been explained by some by pointing out that Marx was primarily dealing with England which could get cheap supply of food and raw materials from overseas. But this cannot be the case of present-day developing countries in which supply of wage goods acts as a constraint on the industrial growth.

It is evident from above that despite several shortcomings in Marx’s model, especially the fall in profit rate due to rise increase in organic composition of capital (i.e., rise in capital-labour ratio), Marx provided important insights into the growth of the capitalist economy which is generally called these days free market economy. Besides, it is Marx who brings out the contradiction in the capitalistic system, viz., reduction in labour costs, which is intended to raise profits, reduces workers’ consumption and lowers the rate of profit. “Technological progress is a treadmill for capitalists—they must run faster just to stand still for technological progress must always keep one step ahead of the rate of capital accumulation.” Marx emphasised the rate of profit and not the level of profits, as determining the capitalists’ investment.

Marx also fully appreciated the capacity of the capitalist system for economic development. Schumpeter says- “Nobody had then a fuller conception of the size and power of the capitalist engine for the future. Marx said repeatedly that it was the historical task and privilege of capitalist society to create a productive apparatus that will be adequate for the requirements of a higher form of human civilisation.” Though Marx predicted that increasing misery of workers and consequent social upheaval will result in collapse of the capitalist system but, according to him, this would occur only after a good deal of economic development had been achieved.

Relevance of Marxian Theory of Capitalist Development for Developing Countries:

The Marxian model is reflective of the socio-economic conditions following industrial revolution in Europe. He saw in capitalistic order the seeds of its own doom and suggested the course it was bound to adopt. At the outset it needs to be pointed out that the parameters in the growth models of earlier writers become the dependent variables in the Marxian framework. The cultural, political and social institutions were regarded as given by the earlier writers.

But Marx conceived them as superstructures determined by the methods of production. The socio-economic and political conditions are regarded by him as reflective of the forces of production. They in course of time generate tensions and contradictions which ultimately give way to revolution. The post-revolution institutions and attitudes, then, reflect the new conditions of production.

Marx, in his sole preoccupation and enthusiasm about the socialistic revolution in the system of production that obtained in the European countries in his times, failed to pay much attention to the problems of economic development of the developing countries. In this regard Alfred Bonne remarks that “Apart from a few allusions remarkable for their determinist note with regard to obtaining prospects for economic development in regions like Western Asia or India, no special attention is given to the problems of change in underdeveloped countries.”

The Marxian concept of under-consumption prima facie appears to have relevance to the conditions prevailing in the developing economies. With the prevalence of low levels of consumption in the developing economies, one is likely to think that the Marxian conviction of crisis in industrial economy applies to the problems of these countries as well. But this is not correct. The main cause of under-consumption in a capitalist economy in the Marxian sense is attributable to the developed system of capitalistic productive forces and the limited purchasing power of the working class.

On the other hand, under-consumption in case of underdeveloped economies refers to nutritional standards below which consumption levels have fallen in these countries. The low level of productive capacity stands in the way of the consumption level of the people in these countries. Such an under-consumption arises mainly due to the low levels of output arising from the underdeveloped productive potential. In contrast, the level of this potential is highly developed in case of capitalist production.

In the same way, Marxian notion of an industrial reserve army does not represent a true picture of the surplus labour in the underdeveloped economies. According to him, the root cause of a reserve army was the introduction of technological improvements or the slow pace of capital accumulation.

In developing economies the surplus labour assumes the nature of disguised underemployment, which is mainly attributable to socio-demographic factors such as traditions of work-sharing by joint family structural obstacles, falling mortality rate, etc. The system of extended joint families keeps the rural masses tied to their farms and obstructs the movement of disguisedly underemployed to industrial employments.

As such, genesis of disguised employment does not lie in technological innovations or a decline in profits due to rise in wages above the subsistence level as is assumed by Marx for the creation of his ‘reserve army’. In this context Marxism fails to offer any solution to this labour surplus problem which has assumed serious proportions in many developing economies.

According to Marx, capitalistic development involved two important characteristics, viz., accumulation of capital and technological improvement. Stagnating underdeveloped economies, he contends, result from the absence of both of these factors. However, it is now well known that this dual criteria—endless capital accumulation and technological change—does not apply to the presently stagnating economies. They operate on entirely different lines than what Marx envisaged for them. They have a social system which is tradition-ridden, lack in technical skill and entrepreneurial ability, possess inefficient administration and are bogged down by immobility of factors of production and structural imbalances. The Marxian analysis in its entirety cannot, therefore, be transplanted to developing economies. A separate analytical scaffolding and policy framework is required to solve their problems.

To say all this is not to completely belittle Marxian theory in so far as its relevance to developing countries is concerned. There are, in fact, certain features of developing economies that closely approximate the conditions that Marx predicted for advanced countries. They may provide certain threads of relevance of his theory to these economies, provided, of course, that they are viewed in a somewhat different setting. For instance, the existence of wage levels close to the subsistence margin resulting in excessive exploitation of labour, the sharply defined class structure with increasing income inequalities and the evidence of increasing misery in some cases are a pointer towards the need for employing a development strategy that is more inclusive.

However, in reality the increasing awareness of such conditions in the developing countries has resulted not in the pure Marxian socialism but a greater role of State in economic development. In an increasing number of developing countries, the State has come to play a more active role in the economic affairs. Many of them have adopted the system of mixed economies. The State has increasingly stepped in to regulate the wages and conditions of workers. The income inequalities have also been sought to be reduced through land ceilings, taxation and other suitable means.

Above all, in his attempt at discovering the laws of motion of capitalism, Marx provided a theoretical construct known as the ‘Departmental Schema’ which is as significant and valid to the developing countries embarking upon the path of planned economic development as it was for market-oriented capitalistic economies. In fact, the applicability of Marxian Departmental Schema has assumed special relevance and significance for the developing economies of today in view of their aspirations to develop themselves and attain maximum welfare in a relatively short span of time.

The crucial problem in the developing countries is the transformation of the ‘potential economic surplus’ into an ‘actual economic surplus’ and its acceleration. Marxian idea of departmentalisation of the economy into two sectors (i.e., capital-goods sector and the consumer-goods sector) is helpful in achieving this end more quickly. By adopting a classification of Department I and Department II, it gives, in fact, a method of inter-industry transformation. It is generic in application, being applicable to underdeveloped and developing countries alike.

Marx categorises the economy into two departments- Department I (capital-goods sector) and Department II (consumer-goods). Representing the constant capital being employed in Department I and Department II by C1 and C2 respectively; the variable capital by V1 and V2, the corresponding surplus values by S1 and S2 and the values of the two Departments by W1 and W2, he states the following formula for describing the total production in each Department-

C1 + V1+ S1 = W1 …… (1)

C2 + V2 + S2 = W2 …… (2)

For Simple Reproduction, i.e., for merely keeping the growth rate of the economy at a constant level with the same stock of capital year after year, Marx points out that the total amount of constant capital used up, i.e., (C1 + C2) must be equal to the total output of the Department I, i.e., (C1 + V1 + S1). And the total consumption (both of workers and the capitalists) must be equal to the total output of the Department II (C2 + V2 + S2).

For economic growth to pick up speed, it is necessary that the Department I should be so rearranged as to become a source of high-yielding economic surplus. This accordingly calls for structural and technological reorganisation. The institutional factors that hinder reinvestment of profits and hence capital accumulation has to be thrashed out quickly. The economic transformation of Department II to make it a surplus-yielding sector involves a still more difficult task to be accomplished. Perhaps the most important and desired step in this direction would be the implementation of a planned programme of land reforms with a view to provide land to the tiller.

This has to be achieved through an appropriate system of land ceilings and the redistribution of the surplus land above the maximum fixed limit in the shortest possible time. Though in the initial years of planning in India, great importance was given to the land reforms laws regarding ceiling on land holdings and reforms in the tenancy system, but unfortunately in the present emphasis on privatisation and liberalisation no actions have been taken to implement them.

Such a programme is expected to go a long way in increasing production by allowing an intensification of agricultural operations, reducing disguised unemployment, increasing employment opportunities, better and more effective utilization of the limited State funds for agricultural development, elimination of middlemen, and the promotion of cooperative and joint systems of farming.

In this way the elasticity of accumulation in relation to agricultural incomes can be considerably increased, thus putting the subsistence sector on a surplus-yielding path. In essence, it means transformation of sector I into II, and this implies the rendering of less developed economies to an increasing application of Marxian ‘Departmental Schema’. Thus, we find the adoption of the Marxian ‘Departmental Schema’ with a view to reorganise the Department I and the transformation of Department II would greatly facilitate and quicken the pace of transformation of a primitive, stagnant and exploitative system into a more progressive and dynamic one. It may be noted that in the developing economies Department I has to play the most crucial role. The pace of economic development is governed by the surplus generated by Department I. A high magnitude of such a surplus over and above the replacement needs of the economy is necessary for the realisation of an accelerated economic growth.

In fact, the planning bodies of the various underdeveloped countries such as India, Burma, Ghana and U.A.R. have been greatly influenced in their plan formulation by the Marxian ‘Departmental Schema’. The Mahalanobis model of growth which formed the basis of India’s Second Five Year Plan employed a growth strategy based basically on the Marxian ‘Departmental Schema’.

In consonance with the Marxian ‘Departmental Schema’, it emphasised the growth of producer-goods sector (i.e., Department I) in relation to the consumer-goods sector (i.e., Department II); the need of a greater role of government in matters of basic allocation decisions in order to regulate private and public sectors; the urgency of making investment decisions to increase their social effectiveness, adoption of necessary organisational and structural changes and the necessity of long-term planning to achieve sustained growth.

Hence, we find that the Marxian formulation of Departmental Schema is of pivotal importance to the developing economies struggling to generate surplus for economic development. The undeniable practical significance of this Schema lies in the fact that it paves the way for realisation of the twin objectives of providing simultaneously for a high rate of growth as well as employment in the developing economies. The applicability of Marxian Schema to the underdeveloped countries also highlights the urgency for the institutional and technological transformation with due emphasis on the development of Department I—i.e., the sector producing the mother of the means of production for the long-run sustained growth.