An eminent development economist, Arthur Lewis, put forward his model of “Economic Development with Unlimited Supplies of Labour” which envisages the capital accumulation in the modern industrial sector so as to draw labour from the subsistence agricultural sector. Lewis model has been somewhat modified and extended by Fei and Ranis but the essence of the two models is the same. Both the models (that is, one by Lewis and the other modified one by Fei-Ranis) assume the existence of surplus labour in the economy, the main component of which is the enormous disguised unemployment in agriculture.

Further, they visualise ‘dual economic structure’ with manufacturing, mines and plantations representing the modern sector, the salient features of which are the use of reproducible capital, production for market and for the profit, employing labour on wage-payment basis and modern methods of industrial organisation.

On the other hand, agriculture represents the subsistence or traditional sector using non-reproducible land on self-employment basis and producing mainly for self-consumption with inferior techniques of production and containing surplus labour in the form of disguised unemployment. As a result, the productivity or output per head in the modern sector is much higher than that in agriculture. Though the marginal productivity in agriculture over a wide range is taken to be zero, the average productivity is assumed to be positive and equal to the bare subsistence level.

Lewis’s Model of Development with Surplus Labour:

In the labour-surplus models of Lewis and Fei-Ranis, the wage rate in the modern industrial sector is determined by the average productivity in the agriculture. To this average productivity is added a margin (Lewis fixes this margin at 30%) which is required for furnishing an incentive for labourers to transfer themselves from the countryside to the urban industries as well as for meeting the higher cost of urban living. In this setting, the model shows how the expansion in the industrial investment and production or, in other words, capital accumulation outside agriculture will generate sufficient employment opportunities so as to absorb all the surplus labour from agriculture and elsewhere.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

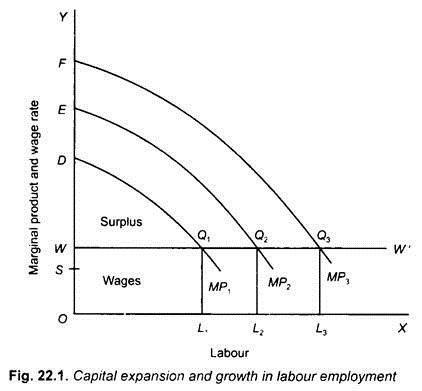

The process of expansion and capital accumulation in the modern sector and the absorption of labour by it is explained by Fig. 22.1. OS represents the real wages which a worker would be getting in the subsistence sector, that is, OS is the average product per worker in the subsistence sector. OW is the wage rate fixed in the modern sector which is greater than OS (i.e., average product in agriculture) by 30%. So long as surplus labour exists in the economy any amount of labour will be available to the modern sector at the given wage rate OW, which will remain constant.

With a given initial amount of industrial capital, the demand for labour is given by the marginal productivity curve MP1 .On the basis of the principle of profit maximisation, at the wage rate OW, the modern sector will employ OL1 labour at which marginal product of labour equals the given wage rate OW. With this the total share of labour, i.e., wage in the modern sector, will be OWQ1L1 and WQ1D will be the capitalists’ surplus. Now, Lewis assumes that all wages are consumed and all profits saved and invested.

Reinvestment of Capitalists Surplus (Profits):

ADVERTISEMENTS:

When the capitalists will reinvest their profits for setting up new factories or expanding the old ones, the stock of capital assets in the modern sector will increase. As a result of the increase in the stock of industrial capital, the demand for labour or marginal productivity curve of labour will shift outward, for instance from MP1 to MP2 in our diagram. With MP2 as the new demand curve for labour and the wage rate remaining constant at OW, amount of labour OL2 will be employed in the modern sector.

In this new equilibrium situation profit or surplus accruing to the capitalist class will rise to WQ2E which is larger than the previous WQ1D. The new surplus or profits of WQ2E will be further invested with the result that capital stock will increase and the demand or marginal productivity curve for labour will further shift upward, say to MP3 position. When the demand curve for labour is MP3 employment of labour will rise to OL3 .In this way, the profits earned will go on being reinvested and the expansion of the modern sector will go on absorbing surplus labour from the subsistence sector until all the labour surplus is fully absorbed in productive employment.

It is worth mentioning that in Lewis model, the rate of accumulation of industrial capital and, therefore, the absorption of surplus labour depends upon the distribution of income. With the aid of classical assumption that all wages are consumed and all profits saved, Lewis shows that the share of profits and therefore rate of saving and investment will rise continuously in the modern sector and capital will continue to be expanded until all the surplus labour has been absorbed. Rising share of profits serves as an incentive to reinvest them in building industrial capacity as well as a source of savings to finance it.

Profit as the Main Source of Capital Formation:

It is clear from the above analysis of Lewis’s model with unlimited supply of labour that profits constitute the main source of capital formation. The greater the share of profits in national income, the greater the rate of savings and capital accumulation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus with the expansion of the modern or capitalist sector, the rate of saving and investment as percentage of national income will continuously rise. As a result, rate of capital accumulation will also increase relative to national income. It is of course assumed that all profits or a greater part of the profits is saved and automatically invested.

It is also evident from above that share of capitalists’ profit depends on the share of the capitalist sector in the national product. As the capitalist or modern sector expands, the share of profits in national product will rise. This rise in the share of profits in national product is due to the assumption of the model that wage rate remains constant and prices of the products produced by the capitalist sector do not fall with the expansion in output. To quote Lewis himself, “If unlimited supplies of labour are available at constant real wage rate, and if any part of the profits is reinvested in productive capacity, profits will grow continuously relative to the national income.”

Credit-Financed Money – Another Source of Capital Formation:

Furthermore, profits are not the only source of capital formation in the Lewis model. It is equally possible to create capital through credit-financed money. Prof. Lewis holds that in an economy marked by scarcity of capital and abundance of the resources, credit creation would have the same effect on capital accumulation as do the more respectable means of profits. In both cases, the ultimate result would be the increase in output and employment.

However, capital formation resulting from a net increase in the money supply would necessarily be accompanied by an inflationary rise in prices. But this is only a temporary phase – a short-lived phenomenon. When the surplus labour gets employed in the capitalist sector for purposes of capital formation and is paid out of the created money, the immediate effect would be the rise in prices. What happens is that while the purchasing power in the hands of workers immediately increases, the output of the consumer goods remains constant for a time. However, the moment the newly formed capital created by credit money is put to use, the output of consumption goods would also rise. Therefore, after a time-lag, the output of consumer goods catches up with the increased purchasing power, and thus the prices start taking the downturn.

Besides, the inflationary process would also be made to die away through another mechanism that operates simultaneously. With the monetary expansion, not only the output and employment rise, but also the profits. As the profits increase relative to national income, so will do the savings. Therefore, the volume of investment being financed out of created money would go on diminishing with the increase in voluntary savings. In the ultimate analysis, the seeds of inflation would be completely killed when the voluntary savings catch up with the ‘inflated level of investment’. Once the equilibrium is restored, new investments, made thereafter, could be financed without having to fall back upon bank credit. With the savings growing into equilibrium with investment, the rise in prices is bound eventually to peter out.

Introducing Technical Progress:

What about the role of technical progress in the type of economic expansion proposed in the Lewis model? Prof. Lewis contends that for the purposes of his analysis, the growth of technical knowledge and the growth of productive capital can be taken to work in the same direction – i.e., to increase profits and wage employment. He argues that to be able to apply new technical knowledge, we ought to have new investments.

If the new technical knowledge is capital-saving, it could be regarded as equivalent to an increment in capital. And if it happens to be labour-saving, it could be regarded as equivalent to an increment in the marginal productivity of labour. In effect, therefore, both cases would produce the same result—an outward shift in the marginal productivity schedule. As such, Prof. Lewis in his model takes the growth of knowledge and the growth of productive capital to be essentially a ‘single phenomenon’.

However, the growth of technical knowledge in the subsistence sector is going to be a different kettle of fish. Its effect would be to raise the level of wages. As such, the capitalists’ surplus would be reduced. It is, thus, that the capitalists have a profound and direct interest in holding down the productivity of labour in the subsistence sector.

Tapering off of the Expansionary Process:

Now, if there is no hitch in the process of expansion and things go on smoothly, the capitalist sector will continue to expand till it has completely absorbed the surplus labour. Then comes the stage where capital accumulation has matched the excess supply of labour. Thereafter, the supply of labour ceases to be perfectly elastic. As a result, real wages, instead of remaining constant, start rising. Also, the share of profits in the national income ceases to show any further rise. And, thus, investment rather than growing relative to the national income comes almost to a standstill.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, the expansion process may come to a halt much before the surplus labour has completely been absorbed. Prof. Lewis suggests three ways whereby the expansionary process might be halted before its natural conclusion.

These are:

(a) The expansion of the capitalist sector may be rapid enough, so that the absolute population in the subsistence sector is greatly reduced, without, of course, affecting the total product. As a result, the average productivity of labour in the subsistence sector will rise. Consequently, the level of subsistence earnings (S) and the capitalist wage (W), are raised thereby reducing the volume of capitalists’ surplus. However, this shall not be if the growth of population happens to be greater than the rate of growth of the capitalist sector.

(b) Technical progress may occur in the subsistence sector and may, therefore, raise the productivity there. This will, in turn, be reflected in a rise in the level of subsistence earnings (S) and the capitalist wage (W). The result, again, would be the squeezing of the capitalist surplus.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) The terms of trade may turn against the capitalist sector due to a rise in the prices of raw materials and food. This is very likely to happen, especially where the modern capitalist sector produces no food products. Now, as the capitalist sector expands, the demand for food will increase. As such, the food prices must rise in terms of the prices of the products of capitalist sector. In other words, the terms of trade would become unfavourable to the capitalist sector. But if the real income of the worker is to be kept constant, the capitalist wage (W) must rise (and so also the subsistence earnings (S)). The effect is that the capitalists’ surplus is reduced.

However, if none of these methods operate or do so only mildly, the capital accumulation will continue to take place. And the modern capitalist sector will continue expanding till the whole surplus labour is absorbed. In any case, the process of expansion cannot proceed indefinitely as wage rate in the modern industrial sector will rise, profits (or capitalist surplus) will decline and as a result capital accumulation will decline and ultimately bringing the growth process to a halt.

A Critical Appraisal of Lewis’s Model:

The validity and usefulness of the labour-surplus model of Lewis for developing countries like India depend of course on the extent to which their underlying assumptions are valid for the economies in question. We are here not interested in validity of all the assumptions, explicitly or implicitly, made in this model. In our view the basic premise of this model is wrong and that makes it unrealistic and irrelevant for framing a suitable development strategy to solve the problem of surplus labour and unemployment.

The basic premise of the model is that industrial growth can generate adequate employment opportunities so as to draw away all the surplus labour from agriculture in a labour developing country like India where population is currently increasing at the annual rate of around 1.6 per cent. This premise has been proved to be a myth in the light of generation of little employment opportunities in the organised industrial sector during over sixty years of economic development in India, Latin American and African countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

For instance, in the 30 years (1951-81) of industrial development in India during which fairly good rates of industrial production had been achieved, the organised industrial employment increased by only 3 million which was too meagre to make any significant impact on the urban unemployment situation, far from providing a solution to the labour-surplus problem in agriculture. Thus, the generation of adequate employment opportunities and as a result the absorption of surplus labour from agriculture in the expanding industrial sector has not proceeded as predicted by the Lewis model.

In may be pointed out here that migration of some workers from the rural to the urban areas in India has occurred as shown by the slight increase in the degree of urbanisation noticed in the various censuses but these immigrants to the urban areas have not been absorbed into the modern high-productivity employment, as envisaged by Lewis and Fei-Ranis. This is evident from the statistical data about meagre increase in employment in the organised sector. These immigrants to the urban areas have been mainly employed in petty trade, domestic service and casual work in which the disguised unemployment and poverty exist as acutely as in agriculture. Thus, as things stand, the traditional sector of the economy is simply moving from the countryside into the cities in apparent contrast to the Lewis model.

Lewis Model Neglects the Importance of Labour Absorption in Agriculture:

A grave weakness of the models of Lewis and Fei-Ranis is that they have ignored the generation of productive employment in agriculture. No doubt, Lewis in his later writings and Fei-Ranis in their modified and extended version of Lewis model have envisaged an important role for agricultural development so as to sustain industrial growth and capital accumulation. But they visualise such an agricultural development strategy that will release labour force from agriculture rather than absorbing them in agriculture. Thus to quote Fei and Ranis – “In such a dualistic setting the heart of the development problem lies in the gradual shifting of the economy’s centre of gravity from the agricultural to the industrial sector through labour reallocation”.

In this process each sector is called upon to perform a special role – productivity in the agricultural sector must rise sufficiently so that smaller fraction of the total population can support the entire economy with food and raw materials, thus enabling agricultural workers to be released; simultaneously, the industrial sector must expand sufficiently to provide employment opportunities for the released workers labour reallocation must be rapid enough to swamp massive population increases if the economy’s centre of gravity is to be shifted over time.

We have shown above that employment potential of organised industrial sector is so little that labour reallocation between agriculture and industry and “smaller fraction of the total population being employed in agriculture” is just not possible in labour-surplus developing countries like India. Indeed, a good amount of employment opportunities can be generated in agriculture itself by capital accumulation in agriculture, adopting proper agricultural technologies and making appropriate institutional reforms in the pattern of land ownership.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Even about the African countries most of which do not suffer from the Malthusian problem of overpopulation but are currently faced with acute urban unemployment (especially of what is known as “Unemployment of School Leavers” majority of which have migrated from the villages to the urban areas) the expert opinion has veered round to the view of seeking solution of labour- surplus problem within agriculture. Thus Sara S. Berry remarks about the African experience – “Most students of the problem of rising African urban unemployment agree that the solution to the problem lies in raising incomes and employment opportunities in agriculture so as to ensure new market equilibrium with more people productively employed in agriculture.

Assumption of Adequate Labour-Absorptive Capacity of the Modern Industrial Sector:

Another related shortcoming of development models of Lewis, Fei and Ranis is their assumption that the growth of industrial employment (in absolute amount) will be greater than the growth in labour force (which in India at present is of the order of about 12 million people per year). Because only then the organised industrial sector can absorb surplus labour from agriculture. The employment potential of industrial sector is so little that far from withdrawing labour currently employed in agriculture, it does not seem to be possible for the organised industries and services, on the basis of existing capital-intensive technologies, even to absorb the new entrants to the labour force.

An important drawback of the Lewis model is that it has neglected the importance of agricultural growth in sustaining capital formation in the modern industrial sector. When as a result of the expansion of capitalist modern sector, transfer of labour from agriculture to industry through agricultural development to meet the additional demand for food-grains, prices of food-grains will rise. With the rise in prices of food-grains wages of industrial labour will increase.

Rise in wages will lower the share of profits in the industrial product which in turn will slow down or even choke off the process of capital accumulation and economic development. Thus, if no allowance is made for agricultural growth, the expansion of modern sector and capital accumulation is bound to be halted. Thus, neglect of agriculture in the development strategy pursued in India since the Second Plan virtually resulted in stagnation in the industrial sector, during the period 1966-1979.

The Assumption of Constant Real Wage Rate in the Modern Sector:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The assumption of constant real wages to be paid by the urban industrial sector until the entire labour surplus in agriculture has been drawn away by the expanding industrial sector is quite unrealistic. The actual experience has revealed a striking feature that in the urban labour markets where trade unions play a crucial role in wage determination, there has been a tendency for the urban wages to rise substantially over time, both in absolute terms and relative to average real wages even in the presence of rising levels of urban open unemployment. The rise in wages, as explained above, seriously impairs the development process of the modern sector.

It neglects the Labour-Saving nature of Technological Progress:

A serious lacuna of the Lewis model from the viewpoint of employment creation is its neglect of the labour-saving nature of technological progress. It is assumed in the model, though implicitly, that rate of employment creation and therefore of labour transfer from agriculture to the modern urban sector will not be proportional to the rate of capital accumulation in the industrial sector.

Accordingly, the greater the rate of growth of capital formation in the modern sector, the greater the creation of employment opportunities in it. But if capital accumulation is accomplished by labour-saving technological change, that is , if the profit made by the capitalists are reinvested in more mechanised labour- saving capital equipment rather than in existing types of capital, then employment in the industrial sector may not increase at all.

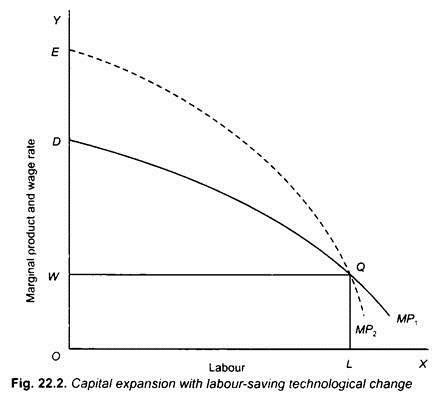

The Lewis model has been reproduced in Fig. 22.2 with a modification that profits made are reinvested in labour-saving capital equipment due to the technological change that has taken place. As a result of this, marginal productivity curve does not shift uniformly outward but crosses the original marginal productivity curve from above. It is evident from Fig. 22.2 that with the constant wage rate OW, the employment of labour does not increase even though marginal productivity curve has shifted to the right.

It will be observed from Fig. 22.2 that though employment of labour and total wage (OWQL) have remained the same, the total output has increased substantially, the area OEQL is much greater than the area ODQL. This illustration points to the fact that while the industrial output and profits of the capitalist class can increase, the employment and incomes of labour class remain unchanged.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Although GNP has increased, labouring class has not received any benefit from it. It is not just theoretical illustration but has been actually borne out by the experience of industrial development of several developing countries. This experience shows that while industrial output has significantly increased, employment has lagged far behind.

Lewis Model Ignores the Problem of Aggregate Demand:

A serious factor which can slow down or even halt the expansionary process in the Lewis model is the problem of deficiency of aggregate demand. Lewis assumes, though implicitly, that no matter how much is produced by the capitalist or modern sector, it will find a market. Either the whole increment in output will be demanded by the people in the modern sector itself or it will be exported. But to think that entire expansion in output will be disposed of in this manner is not valid. This is because a good part of the demand for industrial products comes from the agricultural sector.

If agricultural productivity and therefore incomes of the farming population do not increase, the problem of shortage of aggregate demand will emerge which will choke off the growth process in the capitalist industrial sector. However, once an allowance is made for the increase in agricultural productivity through a priority to agricultural development, the basic foundations of the Lewis model crumble down. This is because a rise in agricultural productivity in Lewis model will mean a rise in wage rate in the modern capitalist sector. The rise in the wage rate will reduce the captalists’ profits which in turn will bring about a premature halting of the expansionary process.

Conclusion:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Despite several limitations and drawbacks, the Lewis model retains a high degree of analytical value. It clearly points out the role of capital accumulation in raising the level of output and employment in labour-surplus developing countries. The model makes a systematic and penetrating analysis of the growth problem of dual economies and brings out some of crucial importance of such factors as profits and wages rates in the modern sector for determination the rate of capital accumulation and economic growth. It underlines the importance of inter-sectoral relationship (i.e., the relationship between agriculture and the modern industrial sector) in the growth process of a dual economy.