The following article will guide you about how fiscal deficit affects economic growth of India.

View about Fiscal Deficit:

How does fiscal deficit affect economic growth is a hotly debated issue. A number of Keynesian economists argue that fiscal deficit promotes growth.

In India where in the last some years since 1996, a good deal of industrial capacity has been lying idle due to lack of aggregate demand, and there has been enough stocks of food grains, it was asserted that fiscal deficit would stimulate demand and thereby ensure rapid economic growth.

In the prevailing economic situation especially from 1996 to 2004 the Indian economy was a demand-constrained economy and therefore the increase in aggregate demand through larger fiscal deficit did not generate inflationary pressures in the economy. If the increase in public expenditure made possible by large fiscal deficit is used for productive investment, especially for investment in infrastructure and rural development, it will boost production and help increase employment opportunities in the economy.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In fact, increase in public investment in infrastructure such as irrigation, roads, highways, is doubly beneficial from the viewpoint of accelerating economic growth. It helps in increasing aggregate demand on the one hand and helps to reduce supply constraints on economic growth on the other.

So the focus should not be so much on reducing fiscal deficit but on reducing revenue deficit. Recall that revenue deficit is the excess of government revenue expenditure (i.e. current consumption expenditure) over revenue receipts.

From the beginning of the nineties since economic reforms have been initiated, there has been large revenue deficits so that a large part of borrowings by the government has been used to bridge the revenue deficit. As a result, capital expenditure on investment in infrastructure and rural development as a percent of GDP declined which has adversely affected economic growth.

Alternative View:

However, from the above it should not be understood that any amount of fiscal deficit or government borrowing is good for economic growth and employment generation. Higher fiscal deficit, that is, borrowing by the government involves payment of interest and raises the burden of public debt.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The large increase in public debt involving large interest payments year after year will not only make the process unsustainable but adversely affect economic growth through reducing investible resources for spending on infrastructure and social sectors. Reviewing the Indian growth scenario World bank Study made in 2004 concludes

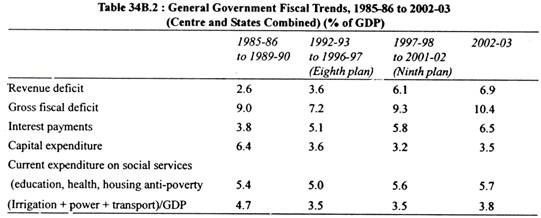

“Interest payments consumed less than 20% of total revenues in the pre-crisis period, compared with over 30% during the Ninth Plan period (1997-2002). Revenue deficits doubled from less than 3% in the second half of the 1980s to 6% during the Ninth Plan period and beyond representing a deterioration in the fiscal stance with spending on social and physical infrastructure crowded out by rising interest and other current payments”.

It will be seen from Table 34B.2 that as compared to the later half of the Eighties, (1985-86 to 1989-90), revenue and gross fiscal deficits (of the Centre and States combined) went up in the 9th plan period (1997-98 to 2002), especially revenue deficit.

As a result, interest payments as per cent of GDP greatly increased. The higher revenue deficits and large interest payments during the nineties caused a drastic decline in capital expenditure and public investment in physical infrastructure (irrigation + power + transport) as compared to the later half of the eighties (1985-86 to 1989-90).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It will be seen from Table 34B.2 that current expenditure on social services (such as education, health, housing, anti- poverty schemes) remained almost stagnant. This shows, according to this view, fiscal and revenue deficits (especially revenue deficit) have worked to lower economic growth.

Adverse impact of fiscal deficit on economic growth has also been shown through its effect on saving and investment in the Indian economy. For example, Shankar Acharya, a former chief economic adviser to the Government of India, has contended that a large fiscal and revenue deficits during 1996-2003 as compared to 1995-96 slowed down economic growth in the second half of nineties and from 2000 to 2003 in India.

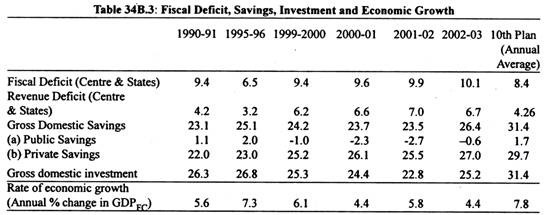

He argued that as a result of fiscal consolidation achieved between 1990-91 and 1995-96, combined fiscal deficit of Centre and States as percentage of GDP declined from 9.4 percent in 1990-91 to 6.5 percent in 1995-96 and revenue deficit fell from 4.2 percent in 1990-91 to 3.2 per cent in 1995-96 (See Table 34B.3).

This freed resources for private investment and in fact brought about investment boom of 1993-96. Gross domestic investment rose from 22.5 percent of GDP in 1991-92 (to which it had fallen during the crisis) to a peak of 26.8 percent GDP in 1995-96 (See Table 34B.3). Gross domestic saving also rose to a record level of 25.1 per cent of GDP in 1995-56. This increase in gross domestic saving and investment, according to Dr. Shankar Acharya, “helped propelled India’s growth to 7 per cent plus for three successive years in the mid-nineties” (1995-96, 1996-97 and 1997-98).

As will be seen from Table 34B.3 after the mid nineties, fiscal deficit and revenue deficit increased which caused the decline in gross domestic saving and investment and thereby contributed to slowdown in economic growth. To quote Dr. Shankar Acharya, “It would be hard to find more telling evidence of the adverse impact of deficits on savings and investment. Of course, other factors were also dampening investment, including the slowdown in reforms, the higher uncertainties associated with coalition government and a worsening international economic environment. But increased borrowing by government (rising fiscal deficits) and the associated high real interest rates clearly played a role in slowing private investment. The drop in aggregate savings and investment took its toll of economic growth, which slowed from 7 percent plus of the mid nineties to around 5 percent in recent years”.

According to him, high fiscal deficits during the eighties created balance of payments deficits as it was mainly financed by external commercial borrowing and therefore did not adversely affect economic growth. But in the later half of nineties rising fiscal deficits were financed by domestic borrowings which were largely used to meet current consumption expenditure and resulted in public dissaving’s (see Table 34B.3).

It may be noted that the implementation during (1997-2000) of Eighth Pay Commission report enhancing the salaries of Government staff both at the Centre and States sharply increased the revenue expenditure of the governments and increased public dissaving’s. This adversely affected domestic rate of saving and investment and lowered rate of economic growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The high and rising fiscal deficits during the period from 1997 to 2003 which resulted in larger government borrowings from the market preempted the needed resources for investment by the private sector. This had an adverse effect on private investment and was mainly responsible for slowdown in economic growth.

Dr. Shankar Acharya’s argument also applies to the growth experience in the 10th plan period (2002-07). As will be seen from Table 34B.3, in the five years of 10th plan on an average annual combined fiscal deficit of Centre and States was reduced to 8.4 per cent as compared to 9.4 to 9.9 per cent in the previous three years which resulted in higher domestic saving (28.2%) and higher domestic investment (27.2%) of GDP.

As a consequence public saving turned positive (1% of GDP) and rate of economic growth rose to 7.8 per cent per annum during this period. Thus in our view both supply-side and demand-side factors play a role in determining economic growth. The growth experience of a country cannot be explained by one type of factors alone.

Role of Fiscal Deficit and Economic Growth: Our View:

However, we do not fully agree with Dr. Shankar Acharya’s view which is similar to that of World Bank. They consider only supply-side factors determining economic growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The fall in growth rate during the period from 1997 to 2002 was largely due to demand recession in the economy caused by:

(1) Reduction in the capital expenditure by Government as a matter of new economic policy initiated since 1991,

(2) Sluggish performance in agriculture during the period, and

(3) World-wide recession during the period.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus demand recession caused a slowdown in the Ninth Plan period (1999-2002) As a result, gross saving and investment rate and GDP growth slowed down. Capital expenditure of government increased substantially in 2003-04 and 2005-06 and with multiplier effects led to the increase in aggregate demand.

This increase in demand also caused increase in private investment and the two together ensured a higher rate of economic growth. In the two years (2005-07) even when Government’s capital expenditure as per cent of GDP fell, under pressure of rise in aggregate demand it was made up by increase in private investment in the two years 2005-06 and 2006-07 which kept the momentum of higher economic growth.

Thus in our view both supply-side and demand-side factors play a role in determining economic growth. The growth experience of a country cannot be explained by supply-side factors alone. In fact, in 2008 and 2009 as a result of global financial crisis there was economic slowdown in India which caused huge job losses. To prevent the situation from worsening further the Government came out with three fiscal stimulus packages to keep the growth momentum.

In these stimulus packages Government raised its expenditure, especially on infrastructure on the one hand and cut taxes on the other to stimulate aggregate demand. To increase its expenditure Government borrowed from the market about Rs. 300,000 crore in 2008-09 Rs. 400, 000 crore in 2009-10. As a result, its fiscal deficit went up from 2.7 per cent of GDP in 2007-08 to 6.0 per cent in 2008-09 and 6.4% of GDP in 2009-10. But this did not produce bad results for the private sector investment, nor did it result in higher rate of interest.

Of course RBI reduced cash reserve ratio to increase liquidity in the banking system and lowered its repo rate to enable banks to lower the lending rates of interest. As a matter of fact, increased borrowing and expenditure by the Government in 2008-09 and 2009-10 led to the increase in demand for the products of private sector.

Therefore, from May 2009 onward there were signs of revival of the Indian manufacturing sector. Manufacturing sector output grew at 9.6% in Sept. 2009 year-on-year basis and this growth further picked up to 17.6% year-on-year basis in Dec. 2009

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Manufacturing sector registered growth of 13.5 per cent in March 2010, 16.5% in April, 2010 and 11.1% in May 2010 year-on-year basis. This shows despite 6.0 per cent fiscal deficit in 2008-09 and 6.4 % in 2009-10 and consequently heavy borrowing by the government in these two years manufacturing output recorded high growth.

Besides, it is because of the fiscal stimulus packages and increase in government expenditure made possible by heavy borrowing and fiscal deficit that India could achieve 6.8 per cent rate of economic growth in 2008-09 and 8.6% in 2009-10,9.3 % in 2010-11 which is quite high, especially when there were recessionary conditions in the US and Europe.

So in our view fiscal deficit of more than 3% in a year is not always bad. All depends on the economic situation in the country and the purposes for which borrowed funds are spent. If there is recession or slowdown in the economy, the fiscal deficit of 6 to 7 per cent of GDP is necessary to lift the economy out of recession or to prevent sharp slowdown in the growth of the economy. If borrowed funds are spent by the Government for investment or building durable assets, it will lead to the expansion in productive capacity and therefore ensure sustained economic growth.

It is evident from above that larger fiscal deficit at the time of recession or economic slowdown far from reducing private saving and investment is helpful for fighting recession or keeping growth momentum of the economy. In fact, the present economic thinking is that even 3 per cent of fiscal deficit should be treated as cyclically adjusted number, that is, the fiscal deficit should go up at times of recession or economic slowdown and should come down in normal or boom period.

The two alternative views regarding the impact of fiscal deficit on our economic growth. One view is of the Keynesian economists who think that in developing economies such as India when they suffer from demand constraint, fiscal deficit provides stimulus to economic growth by bringing about increase in aggregate demand.

In the situation prevailing in India from 1997 to 2002, and then in 2008-2009 the Indian economy in fact suffered from lack of aggregate demand for manufactured products. This demand deficiency problem arose due to bad agricultural performance in some years (there was a negative agricultural growth in 1995-96, 1997-98 1999-2000 and 2000-01 and 2002-03 and also due to sharp decline in public sector investment which started in early nineties following the initiation of economic reforms since 1991.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, during 1997-2002 there was a decline in public investment not only because a good deal of borrowing by the government was used to meet revenue deficit but also because of change in economic policy which aimed at reducing the role of public sector. Besides, public sector investment could not be raised also because of the fiscal policy stance of reducing fiscal deficit as recommended by IMF, World Bank and economists associated with these institutions. In fact the focus of fiscal consolidation was reducing fiscal deficit rather than revenue deficit.

In fact, rates of income tax, corporation tax, excise and customs duties were reduced which resulted in fall in tax-GDP ratio till 2001-02 and caused revenue deficit to rise and therefore much of the borrowing by the government was used to bridge the revenue deficit.

Thus, the fall in public investment was embedded in the new economic policy of reforms. Fall in public sector investment resulted in decrease in aggregate demand on the one hand and shortage of infrastructure on the other which caused slowdown in economic growth during the period 1997-2002. Again in 2008-09 and 2009-10 it was increase in Government expenditure made possible by heavy borrowing and large fiscal deficit that helped India to achieve GDP growth of 6.7% in 2008-09 and 8.6% in 2009-10.

After, 2003-04, the focus of the fiscal strategy of the Government has been to reduce fiscal deficit and revenue deficit by raising more resources through taxes. As a result, the Government succeeded in increasing tax-GDP ratio from 8.1 per cent in 2001-02 to 12.5 per cent in 2007-08, reducing revenue deficit to 1.1% of GDP and fiscal deficit to 2.5 percent in 2007-08.

This enabled the Government to raise public sector investment and also private sector investment with the result that investment rate went up to 38 per cent of GDP in 2007-08. This caused on an average economic growth rate of over 9 per cent in three successive years, 2005-06, 2006-07 and 2007-08.

Thus, in order to ensure economic growth of 9 percent per annum on a sustained basis, focus should be shifted to reducing revenue, deficit. To reduce revenue deficit, steps should be taken to raise tax-GDP ratio and curtail unproductive consumption expenditure of the government so as to eliminate revenue deficit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The borrowings in the capital account should be used for financing public investment in physical infrastructure and social sectors. This will ensure sustained economic growth at the rate of 8 per cent per annum – the objective fixed under the Twelfth Year Plan (2012-17).

Here it may be recalled the Golden Rule of Public Finance, namely, borrowing by the government should be used only for investment purposes and not to meet excess current consumption expenditure except during times of recession. In times of recession even government consumption expenditure will promote GDP growth.

Thus, the focus on merely reducing fiscal deficit at all times and treat it as fetish is not right. In fact, in a demand-constrained economy, a moderate doze of fiscal stimulus is needed. Fiscal responsibility should not be conceived in ritualistic terms of reducing fiscal deficit alone regardless of its effect on the public investment and the economy. In fact, the increase in public investment in infrastructure will also stimulate private investment.

The question of containing Government consumption expenditure, except during periods of recession or economic slowdown, is important but reduction in fiscal deficit should not be elevated to a dogma. A moderate amount of fiscal deficit and associated borrowing is good as long as it is used for increasing public investment in physical infrastructure, education and health of the people. Even foreign investment depends on our success in improving infrastructure.