It is necessary to mention that by economic development we mean not only increase in national income (GNP) or per capita income, but also reduction in unemployment as a result of the growth of employment opportunities and reduction in poverty and inequalities of income. Since economic growth depends on rate of saving and investment and productivity of labour.

We will discuss the impact of population growth on these factors.

It is important to note here that in the present day’s industrialised development countries, in spite of Mathus’ view to the contrary, population growth was beneficial for economic growth rather than retarding it. It has been argued by some that population growth leads to the increase in labour force which is an essential productive resource. By increasing the amount of labour force population growth will help in producing more output. As someone has remarked, population growth brings in more hands to work for production and therefore contributes to economic growth.

Secondly, it has been pointed out that the increase in population leads to the increase in demand for goods. Thus growing population means the growing market for goods is enlarged, they can be produced on a large scale and thus economies of large-scale production can be reaped. The economic history of the USA and European countries shows that growth of population and labour force contributed a good deal to the increase in their national output.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But wheat has been true of USA and European countries may not be true in case of other countries. Whether or not the growth of population contributes to economic growth depends on the existing size of population, the available supplies of natural and capital resources, and the prevailing technology. In the United States, where supplies of natural and capital resources are comparatively abundant, growth in labour force caused by increasing population raises national output.

In India where supplies of other economic resources, especially capital equipment, are relatively scarce, increase in population or labour force does not lead to the employment of all due to scarcity of capital resources. Unemployed people do not add to national output. As for the argument that population growth leads to increase in demand or market for goods, it may be noted that the demand or market for goods increases if the real purchasing power in the hands of the people increases. The mere growth of unemployed or paupers cannot lead to greater demand for goods or expansion in their markets.

Having ruled out the beneficial effects of population growth in the context of the Indian economy, how population growth in India retards economic development are explained below:

1. Population Growth and Rate of Saving and Investment:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Economic growth requires increasing supplies of capital goods. A higher rate of economic growth can be achieved by accelerating the rate of capital formation. Increasing supplies in capital goods becomes possible only with higher rate of investment. And a higher rate of investment, in turn, is possible if the rate of savings is high. Now, increase in population by adding to the number of people whose requirements of “feeding and clothing” have to be met tends to raise consumption and, therefore, lowers both saving and investment.

Coale and Hoover, in their famous work explained that saving rate was reduced by population growth because of increase in burden of dependency. They argued that with high fertility rate among the younger persons and declining mortality (death) rate among the old-age people in the growing population, the proportion of non-working age groups which depend on the working or earning members of their families increases. Since all must consume, in the absence of increase to productivity, saving per person must fall.

Thus rapid growth of population by causing lower rate of savings and investment tends to hold down the rate of capital formation and therefore the rate of economic growth in developing countries like India. Under conditions like those in India population growth therefore actually impedes economic development rather than facilitates it.

Thus Enke writes, “The economic danger of rapid population growth lies in the consequent inability of a country both to increase its stock of capital and to improve its state of art rapidly enough for its per capita income not to be less than it otherwise would be. If the rate of technological innovation cannot be forced and is not advanced by faster population growth, a rapid proportionate growth in population can cause an actual reduction in income per capita. Rapid population growth inhibits an increase in capital per worker, especially if associated with high crude birth rate that makes for young age distribution.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. Investible Resources and Rising per Capita Income:

While, on the one hand, rapid growth in population reduces investible resources for accelerating capital formation, it raises the requirements for investment to achieve a given target increase in per capita income. Suppose population of country A is increasing at 1.5 per cent per annum and that of country B at 2.5 per cent per annum. Given that capital-output ratio is 4: 1, then country A would have to invest 6 per cent of its current income to maintain its per capita income, while country B would have to invest 10 per cent of its current income even to maintain its per capita output. This can be shown by using Harrod-Domar growth formula, namely, g = I/ ν where g is growth rate in national income, / is rate of investment as a ratio of national income and ν is capital-output ratio. The formula can be restated as under –

I= ν.g

For country A with 1.5 per cent annual growth rate of population, its national income must grow (g) at the rate of 1.5 per cent to keep per capita constant.

For this investment as per cent of national income required to keep per capita constant is given by-

I=4 x 1.5 = 6 per cent

And for country B whose population is growing at the rate of 2.5 per cent per annum, its national income must also grow at the rate of 2.5% to maintain its per capita income.

For this, investment required will be-

I= 4 x 2.5 = 10 per cent

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, when the population is increasing at a rapid rate, comparatively larger investment is needed to maintain the current level of income. Thus, given the scarcity of investible resources, adequate resources are not left to raise per capita income significantly.

3. Lower Growth of Per Capita Income:

Like a thief in the night, population growth robs us of most of the gains in national income made from higher investment. Rapid population growth nullifies our investment efforts to raise the living standards of our people. In other words, a high rate of increase in population swallows up a large part of the increase in national income so that per capita income or living standards of the people does not rise much. This is precisely what has happened during the planning era in India.

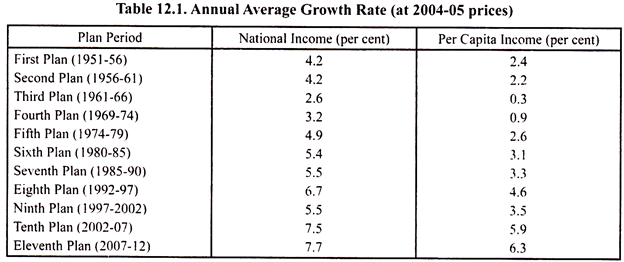

Thus, while the aggregate national income of India went up by 3.6% per annum in the First Plan period and 4.1% per annum in the Second Plan period, per capita income rose by only 1.8 per cent and 2 per cent per annum respectively Average annual growth in national income and per capita income in various Five Year Plan periods in given in Table 12.1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It will be seen from the table that the annual growth in per capita income has been much less than the annual growth rate in the national income. It is the population growing at 2 per cent per annum or more during the planning period that has caused per capita income to rise much less than the increase achieved in national income.

However, since 1991 population growth rate has been less than 2 per cent, it was 1.93 per cent between 1991 and 2001 and 1.6 per cent between 2001 and 2011 on the one hand and growth rate of national income was much higher on the other (Table 12.1). Therefore, the growth rate of per capita income has been relatively higher.

Per capita income (at 2004-05 prices) grew at the rate of 4.6 per cent in the 8th Plan period (1992-97), 3.5 per cent in the 9th Plan period (1997-2002), 5.9 per cent in the 10th Plan period and 6.3 per cent in the 11th Plan period. This higher per capita income growth rate since 1991 has tended to raise the standard of living of the people higher than before.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

That the population growth prevents the rapid rise in per capita income and therefore rise in living standards of the people can be expressed by the following growth formula-

g = Iα – r

Where, g stands for the rate of growth of per capita income, I represents rate of investment, α stands for output-capital ratio (or productivity of capital) and r represents rate of population growth.

Since rate of growth in national income is given by the rate of investment multiplied by the output-capital ratio, Iα will signify the rate of growth of national income. Now, it will be seen that rate of population growth r appears as a negative factor and will, therefore lower the rate of growth of per capita income g. It therefore follows that if rate of growth of per capita income g and the rate of rise in living standards with a given rate of investment is to be raised, the rate of growth of population should be lowered.

4. Population Growth and Marketed Surplus of Food-grains:

Another way in which growth in population is impeding economic development is its effect on marketed surplus of food-grains. The marketed surplus of food-grains is a prerequisite for expansion in non-agricultural employment and output. When a country grows and accelerates its pace of industrialization, it requires food-grains to feed the workers who are employed in industries. If enough surpluses of food-grains are not forthcoming this acts as an important constraint on the industrial development. This prevents the living standards of the people to rise rapidly. Now, marketed surplus of food-grains is the difference between the output of food-grains by the agricultural population and their consumption of them. Thus-

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Marketed surplus of food-grains = (O – Cf).

Where, O stands for output of food-grains, and Cf for consumption of food-grains by the farmers themselves. As about 50% of the population is engaged in agriculture, the most of the increase in population also takes place there. This increase in population in the agriculture raises the consumption of food-grains, i.e., Cf in the above equation and therefore reduces the marketable surplus, if output remains the same. Even if output is rising, the extra consumption by the increase in population tends to lower the growth in marketed surplus for food-grains. We thus see that the growth in population has an adverse effect on the marketed surplus of food-grains and this act as a drag on the growth of output and employment in industries and to ensure food security to the people.

In India, in several years, increase in agricultural output has not been enough and further that the rapid growth in population tends to reduce the growth of marketable surplus and leads to rise in food prices. Rise in food prices relative to prices of industrial goods causes unfavourable terms of trade for industrial sector. This has an adverse effect on industrial development in the country. Besides, over time food inflation gets generalised and causes the problem of general inflation in the country which forces Reserve Bank of India to adopt tight monetary policy (that is, raises its lending rates of interest. The high interest rate discourages private investment and lowers rate of economic growth).

Rapid growth in population in an already over-populated country also raises the problem of food security in the country. The cause of food problem in India is the rapid growth in population since 1951. In order to overcome the shortage of food-grains and to prevent the occurrence of famines in the country, India was forced to import food-grains and spend a good amount of valuable foreign exchange on them. This worsened the balance of payments problem of the country. As a result, sufficient amount of foreign exchange to import materials, machines and equipment for our industries could not be made and this obstructed the growth of industrial output. This also shows how rapid growth in population by causing food shortage inhibits the rate of industrial development.

5. Population Growth and Unproductive Investment:

In his study of population growth and economic development in India, Coale and Hoover focused on the adverse effect of population growth on the resources available for productive investment. According to them, rapid population growth forces the country to make non-productive investment, that is, to invest in duplicating certain social welfare facilities such as the construction of parks, houses, social buildings, sanitation works.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To the extent the Government has to increase its expenses on duplicating these social welfare facilities, investment resources for productive type of capital such as machines for industries, irrigation and fertilisers for agriculture, crucial basic goods such as steal, coal, electricity generation etc. would be reduced. Thus, rapid population growth obstructs economic development by reducing the growth of productive capital.

6. Population Growth and Unemployment:

Economic development requires that employment should increase adequately so that unemployment should decrease. Explosive growth in population causes serious unemployment and underemployment problem in a country. Due to explosive growth in population in India labour force has been increasing rapidly since 1951. In recent years labour force, which was estimated at 309 million in 1983, went up to 333 million in 1988, to 382 million in 1994 and to 406 million in 1999-2000.

As a result of this explosive increase in labour force demographic pressure on the economy has increased resulting in increase in backlog of unemployment and under- unemployment at the beginning of each successive Five Year Plan. In view of this much of our investment efforts are directed at absorbing the growing labour force in productive employment, our ability to raise productivity of labour is severely constrained.

Since production processes in modem organised industrial sector is highly-capital intensive, much of the growing labour force cannot be employed there. As a result, demographic pressure on land and agriculture increases resulting in the severe drop in the net sown area per capita. In agriculture, self-employment is predominant and the joint family system prevails under which both household’s income and work are shared among the family members.

Therefore, in the absence of employment opportunities outside agriculture, much of the additional labour force is forced to remain in agriculture and allied activities. Agriculture performs the role of residual absorber. They share work in agriculture with other family members no matter how low the productivity per person becomes. Thus, with the fall in net sown area per person and increased population pressure, disguised unemployment emerges in agriculture.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Disguised unemployment means more workers seem to be employed in it but quite a large number of additional workers do not add to agricultural output, that is, marginal productivity of workers in agriculture is zero or nearly zero. Since population growth reduces savings and investable resources, it is very difficult to withdraw any significant number of workers from agriculture so as to equip them with the required capital to provide them productive employment outside agriculture. To a certain extent lack of capital may be made up by harder work by workers in a country like India. But such a method of adjustment is not easy to achieve in India.

This is because in the modern times man can produce little with bare hands. To provide them productive employment workers need to be equipped with enough capital goods. Even employment generation in agriculture apart from high yielding inputs such as fertilisers, HYV seeds, pesticides require irrigation works, an important capital needed for extension of double cropping which is a highly employment-generating way in agriculture. Due to lack of invisible resources caused partly by population growth, it has not been possible to extend irrigation facilities to the currently known irrigation potential.

It follows from above that labour force consequences of population growth are to a good extent responsible for huge unemployment and underemployment prevailing in India.

7. Population Growth and Poverty:

The important consequence of rapid population growth is that it has made very difficult to make a significant dent into the problem of mass poverty prevailing in the country. This is clear from the fact that as large as about 18 million people over and above 125 crore populations estimated on March 1, 2011, are being added to our population every year as per 2011 population census. This gives rise to a huge problem of properly feeding and clothing them. Further, as has been explained in detail in the above sections such large increase in population and consequently huge increment in labour force lowers our capacity to make productive investment and thereby to increase productivity of labour to ensure eradication of poverty.

Prof. K. Sundaram rightly writes, “The size of increments to population is itself of some consequence. Thus is because the resource requirements of feeding and clothing even at the current low levels are such that the incremental population itself constraints the ability of the economy to raise the living standards of the existing population.” A vicious circle of poverty operates in this regard.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Rapid population growth leads to lower productivity which causes poverty, poverty causes high infant mortality rate which in turn causes high population growth. There is no wonder then, even after over 60 years of planned economic development, 400 million people live below the poverty line in 2011-12 as per the poverty criteria used by the Expert Committee headed by C. Rangarajan.

Demographic Changes in India and Population Dividend:

India is passing through a phase of unprecedented demographic changes. These demographic changes are likely to contribute to a substantially increased labour force in the country. The census projection report shows that the proportion of working age population between 15 and 59 years is likely to increase from approximately 58 per cent in 2001 to more than 64 per cent by 2021. In absolute numbers there will be approximately 63.5 million new entrants to the working age group between 2011 and 2016.

Further, it is important to note that the bulk of this increase is likely to take place in the relatively younger age group of20-35 years. Such a trend would make India one of the youngest nations in the world. In 2020 average Indian will be only 29 years old. The comparable figures for China and US are 37 and for West Europe 45 and for Japan 48 years. This higher proportion of young labour force in India has a great production potential and has therefore been called demographic dividend’. This demographic dividend provides India large productive opportunities for rapid economic growth.

Thus it has been pointed out that demographics are in India’s favour because working age population is growing faster than overall population. According to the advocates of demographic dividend, the working age population will earn by contributing to production and save more, thereby contributing to higher savings and higher investment which will lead to higher growth. However, in our view demographic dividend poses a great challenge; its benefit will be realized only if our young population is healthy, educated and appropriately skilled and get productive employment.

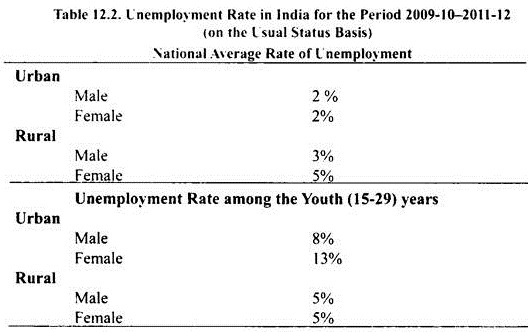

There is nothing inevitable about demographic dividend. Demographic dividend will flow if we are able to find jobs for the growing labour force. According to National Sample Survey conducted between June 2011 and June 2012, the unemployment rate among youth (15-29 years) which made up a fourth (285 million) of the 1210 million total population rose by a percentage point in those two years while national rate of unemployment remained constant.

According to this survey data, as presented in Table 12.2 the rate of unemployment among young Indians (15-29 years) was 8% for urban males and 13% for urban females and for both of them rate of unemployment in this survey period went up. The rate of unemployment in both rural males and females was found to be equal to 5 per cent in the two years of the survey period (2009-10 – 2011-12). Unemployment rate in this period for young women, however, fell.

It follows from above that till 2011-12 no population dividend was accruing in case of India. Thus unless adequate employment opportunities are generated in the process of economic growth, benefits of population dividend will not be reaped. If the advantage of population dividend is to be availed of, high priority should be given to the generation of employment opportunities. For this the youth should be properly educated and imparted right types of skills.

Population Control Policy:

Over-populated developing countries are currently facing the problem of population explosion. The population growth is swallowing up a large part of the gains in national income brought about by planned economic development. If we want that future generations should have at least as much good prospects of living as the present generation we must control population growth.

India’s population which is presently about 1250 million is increasing at a rate of about 1.6 per cent per annum. If current trends continue, India may overtake China in 2045 to become the most populous country in the world. At present about 50 per cent of India’s population is below 20 years of age. Hence, a large number of our present population will live to see by the middle of the 21st century the disastrous consequences such as acute poverty conditions, widespread unemployment a high degree of socio-economic tensions if current growth in population is not checked.

The check on the growth of population is therefore absolutely essential if we want to solve problems of mass poverty and widespread unemployment. Further, if the economy is to be prevented from reaching the stationary state, controlling population growth is essential to achieve this aim.

Stressing the importance of controlling population, growth in India is characterised by economic growth, the existence of mass poverty and unemployment. Prof. PR. Brahmananda writes, “A stationary economy with an open ended population expansion angle will be the greatest permanent disaster for the country. All hopes of improvement in living standard even at the meagre levels of vast masses will have been forever dashed to pieces”. He further adds, “Such an atmosphere cannot be conducive for economic progress. The prospect of more bread being ruled out, the flow of freedom may not flutter for long.”

Now, an important question is as to what policies can be adopted to control population. Population growth depends on the fertility rate (birth rate) and death rate. Thus, policies that have to be adopted to check population growth should aim to reduce the birth rate. The increase in birth rate is ruled out for obvious reasons. Population growth can be reduced by reducing the birth rate. That is, each family should have smaller number of children. It may be noted that reducing fertility rate in under-developed countries is quite a formidable task.

This is because, as has been pointed out by Kuznets, “in underdeveloped countries people have an intense tendency to have more children because under the economic and social conditions large proportions of the population see their economic and social interests in more children as a supply of family labour, as a pool for a genetic lottery, and as a matter of economic and social security in a non-protecting society.”

The various policies that may be adopted to control the growth of population are as follows:

(a) Family Planning Programme,

(b) Sterilisation,

(c) Promotion of education,

(d) Social and economic development, especially of the poor sections of the society.

(a) Family Planning Programme:

This is an important policy measure that has been adopted by several developing countries. India is the first country in the world to adopt family planning as a State policy. Under family planning programme various contraceptive devices and health services are provided to encourage the couples to adopt small family norm, that is, to have fewer children. Through various communication media a wide publicity is given that couples should go in for only two or three children and no more. An appeal is made to them that their life would be happy and prosperous if they have small family.

Recently, policy of providing economic incentives and discentives has been adopted in some countries to discourage the people from having more children beyond a certain number which is generally fixed at two or three.

Some of the incentives and disincentives adopted to promote family planning are:

(i) Elimination or reduction of maternity leave and benefits beyond a certain number. This will discourage the employed women to bear more children.

(ii) The establishment of old-age social security provisions, such as old-age pension. This greatly helps in motivating the people to have smaller number of children. As is well known, in poor countries like India, people have a tendency to bear more children so that in their old age security be ensured.

(iii) Money payments to those who opt for small families and voluntarily go in for sterilisation operation,

(iv) Allotment of scarce public houses, housing plots, flats etc. on the basis of preference to those who have a small family. Besides this, several other incentives and disincentives have been devised to encourage the small family norm.

For the success of the family planning programme a variety of medically tested and safe contraceptives such as IUD pills, condoms, foam tablets, jellies and others should be made freely available. It may be noted that a great boost was given to the family planning programme by the discovery of IUD (intrauterine device), popularly called as loop. But after some time ‘impression was created among the female population that it was not very safe. The need of the hour is to strengthen the research in contraceptive technology and such devices should be discovered which should be effective but minimise the health risk. In India, after the experience of several years, there has been some reconsideration of the various aspects of the family planning programme.

Family planning programme would now be an integral part of comprehensive family welfare policy covering education, health and childcare, family planning and women’s rights and nutrition. The accent in new policy is on integrating contraception with public health, medical care, maternal and child health and nutrition. In fact, the name of the ministry has been changed from Ministry for Family Planning to Ministry of Family Welfare. In so far as it goes, the new orientation may prove to be good but it needs to be stressed, as shall be brought out later, that the success of family planning programme depends heavily on the process of social and economic development.

(b) Compulsory and Forced Sterilisation:

As effective policy measure to check the growth of population, compulsory sterilisation has been suggested by many. According to this, it should be made compulsory for the couples to undergo sterilisation beyond a certain number of children, say two or three. Those who violate this, either penalty may be imposed or they are forced to undergo the operation. Admittedly, this is a drastic measure, but is considered very effective in the context of the failure of voluntary family planning programme.

Of all the measures involving several incentives and disincentives proposed, the most controversial is the proposal of compulsory sterilisation. According to this proposal, compulsory sterilisation of every couple who has more than two children should be introduced. This suggestion of introducing an element of compulsion in the sterilisation programme implies that one is not hopeful of various incentives and discentives succeeding in achieving the objective of stabilising the population size. It may be noted that people of India have already rejected the policy of compulsory sterilisation adopted during the emergency period 1975-77.

In India during the dark period of emergency the policy of forced sterilisation was in fact adopted, though officially it was described as voluntary. In the name of motivation campaign, family planning camps were set up where people were forcibly driven to undergo operation. Ambitious targets were laid down which were successively revised upwards. In fact coercion came to be used on a large scale, especially in the States in the North, so that the programme was voluntary only in name.

The State Chief Ministers vied with each other to surpass their targets and excesses were committed in the process. In 1976 while the target of sterilisation originally fixed was 43 lakhs, actually 75 lakhs sterilisations were affected. Little wonder, the official over-enthusiasm and excesses made the whole programme highly unpopular and this was one of the main causes of Congress Party’s utter rout in the Northern States in Lok Sabha elections of March 1977.

In the opinion of the present author, the policy of forced sterilisation is quite inhuman; it is treating human beings as animals. Public opinion is strongly opposed to it. Moreover, when there are several contraceptives available, recourse to compulsory sterilisation is not needed.

(c) Promotion of Education:

Empirical studies conducted in several countries reveal that there is inverse relation between the fertility rate and education, especially of women and girls. Therefore, an important measure to reduce the birth rate is the promotion of education, especially among female population of the country. The educated men and women accept small family norm and more readily take family planning measures such as use of contraceptives. Moreover, when educated women are employed, their tendency to bear and rear more children falls.

Dr. Ashish Bose, an eminent demographer, in 1978 pointed out that India’s family planning campaign has been severely handicapped because of the slow rise in the literacy level. To quote him, The sad fact remains that in large parts of India, especially in U.P., Bihar, Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan, women literacy rate in the rural areas is less than 10 per cent. And these are States where the progress of family planning is slow. These four States account for 39 per cent of India’s population. So their impact (or lack of it) on the national birth rate is bound to be significant. However, efforts to educate the people especially women, both formally and informally, be strengthened to achieve the target of reduction in birth rate.

(d) Social and Economic Development:

It has been said that “development is the best contraceptive.” This implies that with social and economic development, the birth rate will go down, as people with higher levels of living prefer to have fewer children. First, people with a higher level of living do not need children to supplement the family’s meagre income. Secondly, they come to prefer “quality” of children rather than “quantity”.

Thirdly, their desire to further improve their level of living increases and this induces them to practice family planning measures. In the opinion of the present author, if the population growth in India has remained virtually unchecked in spite of a nationwide family planning programme, the fault does not lie solely with the programme but to a much greater extent with the character of social and economic development in India which has failed to remove mass poverty and improve the levels of living of the poor and weaker sections of the society.

Accordingly, if population is to be effectively checked, not only the tempo of economic development should be speeded up but strategy of development should be such as will promote employment opportunities for the poor, especially landless labour, marginal and small farmers. It should be ensured that fruits of economic development should reach these poor people. For this land reform measures and income redistribution policies should also be effectively implemented. If the standards of living of the poor go up as a result of economic development, they will readily adopt small family norm.

Population and Poverty:

Population growth leads to the increase in poverty in developing countries in more than one way. First, rapid population growth swallows up a large part of annual increments in national income brought about by increase in investment or capital formation so that per capita income or level of welfare does not increase much.

For example, as is seen from Table 12.1 that in India’s Five Year Plans at least up to the 5th Five Year Plan (1974-79) a good part of the growth in national income was earned by growth in population and therefore rise in per capita income or level of welfare did not go up significantly. This is because of lower growth in per capita income until 1980 that India did not succeed in making much progress in reduction of absolute poverty.

Population growth adversely affects the problem of poverty indirectly through lowering the rate of saving which does therefore permit higher rate of investment or capital accumulation. With lower rate of investment or capital accumulation rate of growth of national income or GDP remains lower which makes it difficult to make a large dent into the problem of poverty. It is generally believed that the stable solution to the problem of poverty requires stepping up rate of economic growth. Thus by lowering the rate of saving and investment, population growth is a great impediment to eradication of poverty in developing countries like India.

It is worth noting that the findings of Coale and Hoover in their important study of India’s population problem in the fifties. According to Coale and Hoover, faster population growth affects the age structure of the population toward the very young and therefore causes the dependency ratio in families to rise. The higher dependency ratio in the families tends to reduce their saving rate. The lower savings cause lower rate of investment which is an obstacle in the way of speeding up economic growth and reduction in the poverty problem.

Further, Coale and Hoover, in their study of population growth and development, found that with rapid growth of population and labour force more resources need to be used for expansion of social expenditure on parks, hospitals roads, houses etc. and little resources are left for increase in capital per worker to raise labour productivity. This hinders higher growth in income per capita. A vicious circle of poverty operates in this regard. A rapid population growth lowers labour productivity which causes poverty, poverty causes high fertility rate which in turn causes high population growth rate. There is no wonder then that according to the poverty criteria fixed by Rangarajan Expert Committee 400 million people in India lived below the poverty line in 2011-12.

A similar argument of rapid population growth affecting our ability to raise the living standards of the people or to reduce poverty has been advanced by Prof. K. Sundaram of Delhi School of Economics. According to him, the large increase in the extra number of people due to rapid population growth (around 18.2 million extra population every year as per latest Population Census 2011) requires resources for feeding and clothing even at the current low level so that little is left for raising the living standards of the existing population. To quote him, “The size of increments to population is itself of some consequence. This is because the resource requirements of feeding and clothing even at the current low levels are such that the incremental population itself constrains the ability of the economy to raise the living standards of the existing population.”

That rapid population growth causes increase in poverty can also be known from its effect on agriculture. Increase in population raises population pressure on arable land and reduces land-man ratio which causes lower productivity per person and leads to disguised unemployment and poverty. Not only that, rapid growth in farming population in India led to subdivision and fragmentation of land holdings which renders cultivation on tiny land-holdings unviable.

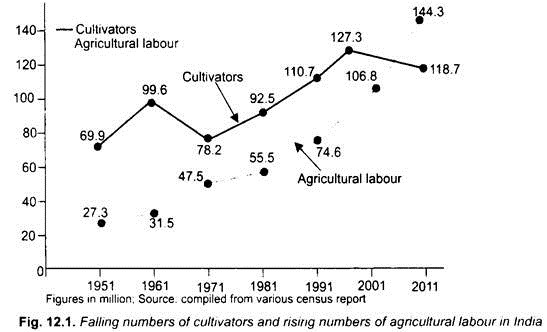

Not able to meet their basic needs with cultivation of tiny land holdings, many cultivators sell their land and join the ranks of landless agricultural labourers. As a result, as is seen from Fig. 12.1, in India the ratio of cultivators in agriculture has been falling and that of agricultural labour has been increasing. According to Population Census of 2011, even the absolute number of cultivators in agriculture declined in 2011. Due to the increase in agricultural labour, many of them do not find work in agriculture for a good part of the year and therefore remain unemployed.

Population and Environment:

Population growth raises concern over environment issues because it is thought that basic needs of growing population may not be adequately met by earth’s natural resources resulting in fall in living standards of the people. This is because increasing population causes environmental degradation by making forest encroachment, deforestation and depletion of firewood. Increases in population cause over-exploitation of natural resources such as forests, water, fisheries and minerals at a rate far greater than their capacity to regenerate.

Besides, population pressure on land compels us to cultivate arable land more intensively by using chemical inputs such as fertilizers, pesticides which cause soil degradation. Further, increase in population through its effect on deforestation by the rural and urban population for timber and fuel leads to the increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere and therefore causes air pollution.

Thus the population impacts on environment primarily through the use and depletion of natural resources and is associated with environmental problems such as air and water pollution and loss of biodiversity and increased pressure on arable land. As an example of estimate of loss, Tata Energy Research Institute (TERI) estimates that economic losses due to soil degradation, diseases caused by pollution and forest degradation is between Rs 1,00,000 and 4,50,000 crore every year and this does not include a series of other losses due to ecological destruction.

Populations increases cause over-exploitation of land and water resources and loss of biodiversity and forests and will therefore endanger sustainability of agriculture and food security in the country. According to Prof M.S. Swaminathan, a noted agriculture scientist, ” The capacity to support even the existing human and animal population has been exceeded in many parts of the world’ and if population growth is not checked, it will endanger the attainment of food security. To quote him again, “In the recent years there has been considerable concern about human capacity to produce adequate food to meet the needs of the growing population and the increase in purchasing power resulting in higher consumption of animal products.”

It is manifest from above that rapidly increasing population in developing countries will lead to the over-exploitation and degradation of land and depletion of fisheries which will threaten the achievement of food security in the developing countries.

Besides, the growth of urban population in the absence of adequate infrastructure facilities has caused the lack of clean water to drink and given rise to urban slums with the poor sanitation which has increased the vulnerability of the people to several diseases. It follows from above that to meet the expanding needs of the developing countries, environment degradation must be halted. For that purpose, reduction in population growth will greatly help in easing the intensification of many environmental problems.

Poverty in developing countries is also said to be responsible for environmental degradation. Poor people rely on natural resources more than the rich. For survival the rural poor are forced to cut forests for timber and fuel as well as graze animals on pasture lands more than the reproductive capacity of these natural resources. Besides, when the cultivable land becomes short relative to population, the poor are forced to make their subsistence by cultivating fragile land on hills and mountains resulting in soil erosion on a large scale. It is in such environment that poverty becomes a vicious circle. Poverty leads to land degradation and land degradation accelerates the process of impoverishment because the poor people depend directly on exploitation of natural resources on which property rights are not properly assigned.

Thus, though a large number of poor people earn a good deal of their livelihood from the unmarketed natural resources such as common grazing lands, forests from where food, fuel and building materials are gathered by them, the degradation and loss of such resources may harm the poor and result in perpetuation of their poverty.