This article throws light upon the seventeen economic terms and their basic concepts.

“Every science frames its concepts in unique terminology and develops its own vocabulary. Economics too has its unique vocabulary. – M. Bober”

1. Utility:

Utility, economic welfare, satisfaction, and sometimes happiness — these terms are often used in economics in more or less the same sense. But this is not correct. In fact, to say that someone derives utility from a good or service is to say that he prefers the goods to exist rather that not to exist. To say that he derives more utility from good X than good Y is simply to say that X is preferred to Y. The concept may now be explained in detail.

Human wants can be satisfied by the use of material objects or by personal services. Thus, hunger can be satisfied by eating bread which is a material object. The desire for music can be satisfied by hearing a song sung by a singer. What a musician performs is a service. We may say that bread has the power to satisfy human wants.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So also has the musician. The term utility is used to denote this want-satisfying power? Thus, utility means the power to satisfy human want. Such power exists in material things and various services. We must not confuse between a thing and its utility. Bread is a thing. Bread is not utility. It has utility.

Utility is an abstract idea. Some economists believe that it cannot be measured. According to them, it is not possible for any person to say ‘how much’ utility he derives from the consumption of a particular article. According to other economists, it is possible to measure utility in terms of money. Thus, if a man is prepared to pay 80 paise for a slice of bread, the utility he derives from it is measured by 80 paise.

Although there is a difference in opinion on the questions whether utility is measurable, all economists are agreed that it is possible for a man to compare between two things and say whether one of them has more utility than the other or less. Thus, it is possible for a man to say that he gets more utility from a glass of lemonade than from a glass of water.

The same thing may have different utilities to the same man at different times. When he is very thirsty, a glass of lemonade may give him much utility. It will give him less utility when he is less thirsty. Thus, utility varies according to time and circumstances.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Again, the same article may give different utilities to different persons. A person may prefer lemonade to water. Another person may prefer water to lemonade. Utilities derived and preferences shown depend upon the habits and taste of the individual. These ideas are expressed by saying that utility is a relative concept.

It is to be noted that the term utility in Economics is without any moral or legal implication. Drinking wine is immoral. But many men desire to drink wine. Economists will say that wine has utility because it has the power to satisfy some men’s want. Arsenic is a poison with which a man may commit suicide. Any suicidal act is unlawful. But some men may want to have arsenic. Therefore, it has utility in the economic sense.

Different Kinds of Utility:

a. Elementary or Natural Utility:

The utility that we get from things obtainable free from nature may be called elementary or natural utility. Air and water have this kind of utility.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

b. Form Utility:

Utility may be created by changing the shape of matter. When a carpenter makes a chair out of a pieces of wood, he creates a thing which is more useful to men than pieces of wood. This type of utility is form utility.

c. Place Utility:

Utility may be created by transferring a thing from one place to another. Coal in Asansol is not useful to a man of Calcutta. When the coal is transferred to Calcutta it acquires greater utility. This type of utility is called place utility.

d. Time Utility:

The same thing may have different utilities at different times. The utility of a commodity increases at certain times and declines at other times. Thus, new dresses for children give more utility during the Puja season than at other times. By supplying commodities at the appropriate time utility is created. This type of utility is created by shopkeepers and others by holding over things from one point of time to another.

5. Service Utility:

Personal service can have great utility. Thus, the work of a cook or a servant or a travel agent or a banker creates utility. This is called service utility.

6. Possession Utility:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Some people derive satisfaction just by having something. An individual having three watches may feel happier than having only one. He may not even use all the watches. He way may simply feel happy by possessing them.

Utility Function:

It is a function stating that an individual’s utility is dependent upon the goods he consumes and their amounts.

It may be explained as:

U = f (x, y, z,…)

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Where x, y and z are the amounts of the goods under consideration.

2. Goods:

Our wants are satisfied by goods and services. Goods, commodities, products or articles refer to material objects.

Goods refer to tangible commodities which contribute positively to consumer welfare. These use distinguished from bads. Services are nonmaterial; they represent the actions of individuals, like medical examination of a patient by a doctor, song of a singer, or a lecture by a professor. The capacity or the quality of a good or service to satisfy a want is called utility. Utility denotes the importance/the significance, or the usefulness which we find in a good or in a service.

The term goods is used in ordinary language to mean physical things which are bought and sold in the market. In Economics the term is used in a wider sense. Goods, in Economics, mean anything which has the power to satisfy human wants, or, in other words, anything which has utility. Thus, the term includes material things like rice, bread, cloth, etc. It also includes non-material things like the services of the doctor, lawyer and musician.

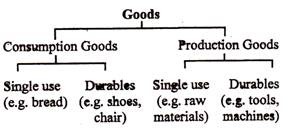

Classification of Goods:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Goods can be classified in various ways as follows:

a. Material and Non-material:

Rice, vegetables, books, houses, water, air, etc., are examples of material goods. The services of a doctor, the goodwill of a business, etc., are examples of non-material goods. The treatment of a patient by a doctor, the delivery of a lecture by a professor or the singing of a song by a singer are called services in Economics.

b. External and Internal:

Physical things are external to men and are called external goods, e.g., furniture. Internal goods are qualities which enable a person to perform a service and thereby satisfy a human want. The musician has certain qualities which enable him to give pleasure to other human beings. These qualities are sometimes called internal goods. Some economists prefer to call internal qualities personal capital.

c. Transferable and Non-transferable:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The ownership of goods like houses, agricultural farms, furniture, etc. can be transferred from one person to another. They are called transferable goods. There are types of goods which cannot be transferred, e.g., the musician’s ability or the doctor’s skill.

They are called non-transferable goods. It is to be noted that by transfer we mean transfer of ownership. Physical transferability from one place to another is not necessary. Thus, an agricultural farm is transferable although it cannot be moved from one place to another.

d. Free and Economic Goods:

Some goods ready for use are supplied by nature in such abundance that no one has to make any sacrifice in making more use of them. These goods are not scarce in relation to wants; such goods are free goods, because many of them are not bought and sold. So they have no price. They create no economic problems and they are not studied in economic analysis.

Examples of free goods are air, sunshine, wild flowers in the woods. In today’s world there are few free goods. Most goods are economic goods, goods scarce in relation to human wants and, therefore, bought and sold at a price. Economic goods may be provided by nature, without effort on our part. Examples are land, ores and oil under-ground, or virgin forests. But most economic goods embody in them a good deal of human effort, as does coal in the bin of the coal dealer, ice-cream, machinery, or houses.

A good may be free when not scarce and an economic good as soon as its amount becomes limited in relation to human wants. The free land occupied by the people at the dawn of civilisation soon became an economic good.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In fact, the same article may be free at one place while it is not free at other places. Drinking water is free by the side of a river. It is not free in a town like Calcutta because it has to be stored in tanks, chlorinated and then pumped out to the different houses. Goods which are in abundant supply are usually free goods, e.g., air. Goods which are scarce in relation to the demand are generally not free. Economic goods are also called wealth.

e. Consumer Goods and Capital Goods:

Some goods yield satisfaction directly as the consumer uses them, as does bread or a Maruti car. These are called consumer goods. Other goods help produce consumer goods. They are natural resources, raw materials, tools, machines, office buildings. Of these, the goods made by men are called capital goods, and those provided by nature, such as forests, minerals, and any other natural resources, are called land.

The automobile used by the physician while doing his duty is a capital good. The same automobile when use by the physician for a pleasure trip is a consumer good. The aggregate of economic goods in existence in a community constitutes its wealth. This concept does not include any service which is also an economic good.

The classification of goods can be illustrated by the following chart:

3. Resource Allocation:

When purchasing raw materials, employing labour and undertaking investment, the business firm or the producer is involved in resource allocation. Society’s resources are, inevitably scarce so that the individual firm has to pay for them.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

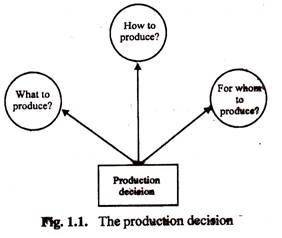

Decisions need to be made at three levels, namely:

i. What goods and services to produce with the available resources;

ii. How to combine the available resources to produce different types of goods and services, and

iii. For whom the different goods and services are to be supplied.

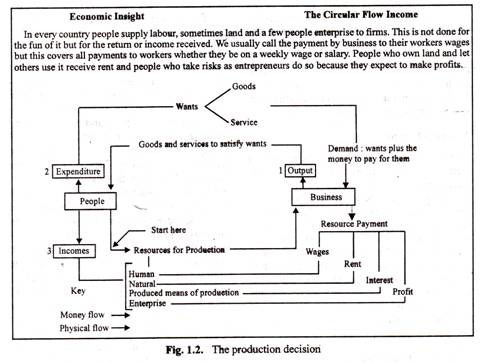

Figure 1.1 illustrates the interrelationship between the production decision and decisions regarding these three factors. Such decisions are sometimes described as the allocative, productive and distributive choices, respectively, which face society in general. In business economics we examine how the price mechanism relates to making these choices.

Traditionally, the price mechanism has been seen as the major determinant of the what, how and for whom decisions — especially in market economies, though less so in the formerly centrally planned or command economies of Eastern Europe. However, over time in all economies firms have grown in size and importance – witness for example resource allocation which goes on within companies such as IBM, ICI and Toyota.

Resources within firms are allocated by both command and price. For example, a decision on where to locate plant could be based upon detailed costing of alternative sites (price). Alternatively, the decision might be made by management on the basis of non- price factors, which may in fact be purely subjective (‘a nice area of the country to live’).

X-Efficiency:

This term refer to a situation in which a firm’s total costs are not minimised because the actual output from given inputs is less than maximum level of output that can be produced by improving technical efficiency of the product process.

4. Wealth:

Wealth means economic goods. Free goods are not counted as wealth.

In economics anything which has market value and can be exchanged for money or goods can be regarded as wealth. It can include physical goods and assets, financial assets and personal skills which can generate an income. These are considered to be wealth when they can be traded in the market for goods or money.

The meaning of the term wealth can be further analysed as follows:

We have that goods are articles having the power to satisfy human wants. All goods have utility. Wealth is a class of goods. Therefore, in order to be called wealth an article must have utility. Again, free goods are not wealth. Therefore, wealth consists of things which are scarce.

Utility and scarcity are the two most important characteristics of wealth. In addition, wealth must satisfy two other characteristics. It may be transferable and it must be external to man. If an article is not external, or if it is not transferable, it does not come within the category of goods and, therefore, cannot be called wealth.

Characteristics of Wealth:

This characteristics of wealth are the following:

a. Wealth has utility:

A thing without utility is not goods and, hence, is not wealth. Nobody will incur any cost for the purpose of obtaining a thing without utility.

b. Wealth consists of scarce goods:

Nobody will pay anything for something which can be obtained free from nature. When a thing is scarce, it is necessary to pay money or incur labour for the purpose of getting it. Only scarce goods are called wealth.

It must be noted that scarcity is a relative term. A thing may be scarce in some places or times while it is free in other places and times. The air that we ordinarily breathe is available without any cost. But the air that we breathe in an air-conditioned cinema hall has to be pumped in and out at a cost. Such air is not free. It has a cost which is included in the price of the cinema ticket. It can, therefore, be called wealth.

c. Wealth is transferable:

A thing which cannot be transferred from one person to another is not a good and therefore not wealth. The ability of a musician cannot be transferred to another. It is not wealth. But a house, a plot of land, things like rice, furniture, etc., can be transferred from one person to another. They are, therefore, wealth. It is to be noted that transfer means transfer of ownership, not transfer from one place to another. Nevertheless, it is wealth because its ownership can be transferred and it possesses the other features of wealth, viz., utility and scarcity.

d. Wealth is external to human beings:

An internal quality is not transferable and is, therefore, not wealth. The health of a man, the skill of a musician, the dexterity of an artist or doctor, etc., are of great utility to their possessors and are also scarce; but since these are not transferable, they cannot be called wealth. In ordinary language, we often say that health is wealth; but in Economics we cannot call it wealth. Internal qualities are sometimes called personal capital because the possession of good qualities enables a man to earn an income.

There are some non-material goods which show all the characteristics of wealth. For example, we may cite the case of the goodwill of a firm, which means the reputation (or good name) which it may have acquired in course of business. The goodwill can be sold. It can, therefore, be described as wealth. Thus, wealth may be material as well as non- material.

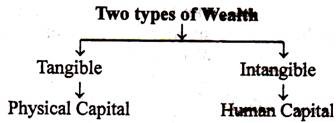

Wealth can be subdivided into two main types tangible, which in referred to as capital or non-human wealth; and intangible which is human capital.

See chart below:

All wealth has one basic property — it can generate income. So income is the return to wealth. Thus wealth is a stock, but income is a flow. A stock variable has no time dimension, but a flow variable has such a dimension (i.e., so much per period). For example, your fixed deposit in a bank is a stock. But the annual interest that you get is a flow. (The present value of this income flow constitutes the value of the stock of wealth.)

Wealth and Welfare:

Wealth is simply a stock of goods. Welfare is the derivation of satisfaction from possession of wealth. The very possession of a huge amount of wealth may make a man psychologically happy. But an increase in wealth does not necessarily imply an increase in welfare, because welfare depends upon a host of factors — economic and non-economic — of which wealth is just one.

Quite the reverse could conceivably result. A man possessing wealth of Rs. 3 lakhs is not necessarily thrice as happy as a man who owns only Rs. 1 lakh. Economists like Pigou, however, are of the opinion that increase in wealth increases welfare and a decrease in it implies a loss of welfare.

But even from the national point of view, an increase in wealth may not increase welfare. If a factory is established, new production will be generated and so wealth of the community may increase in the process. But the factory may emit smoke and dirt and may increase the laundry charges of the people residing in the area and reduce their welfare. It may also reduce the price of land in the adjoining areas by causing situational disadvantage.

Likewise an increase in income does not always bring forth an increase in welfare. The college teacher, who becomes a factory manager, may have larger income but not more welfare. Or, contrarily, a man who resigns his post of an engine-driver on medical advice and takes up a clerical job elsewhere has a smaller income but an increased welfare. Welfare in itself is a highly abstract term, which is difficult to define in precise terms. Yet the increase of welfare is of paramount importance in any society.

Wealth and Capital:

We have said earlier that wealth, in economics, refers to a stock of economic goods. Furthermore, wealth is referred to as accumulated income. Thus, wealth is a stock concept. For instance, an individual’s wealth is regarded as the stock of all economic as well as transferable goods possessed by him. On the other hand, capital may be defined as that part of an individual’s stock from which he expects to derive any income.

So, capital is also a stock concept. But there is one fundamental difference between wealth and capital. Capital is defined as the part of wealth or stock of material goods which facilitate the production of goods or wealth. From this definition, we can say that wealth here serves as an agent of production. No doubt, a car owned by a doctor is his wealth, but once he uses it for doctoring to earn more wealth then this car becomes capital. Thus, all wealth is not necessarily capital but all capital is wealth.

5. Income:

Income, too, should be viewed differently from wealth. Wealth is a collection of goods while income is a flow of utility created by man and wealth during a certain period of time. Thus, wealth is a store of utility and income is a flow of utility.

Let us illustrate the point by some examples. The house we live in is wealth, but the utility we derive from that house by living in it year after year is income to us. Again, if a person owns a motor car, it is wealth to him; but the service that he gets from the car is income to him. Similarly, dividends are income, while shares are personal wealth (capital).

An individual usually distributes his total wealth among two types of assets money and bonds (share of companies). A share is to be distinguished from a stock — a particular type of security, usually quoted in units to Rs. 100 value rather than in units of proportion of total capital, as in shares. The term stock is now coming to mean exclusively a fixed interest security, i.e., loan stock in a company or local or Central Government stock.

People derive income not only from wealth but also from various non-material sources. Doctors, teachers, lawyers, film-stars, and others also satisfy our wants through their services. These services should also be included within the concept of income. Thus, the real income of a person is the amount of goods and services which he gets during a certain period of time.

In this context it is worthwhile to remember that changes in money incomes do not always imply changes in the real incomes or in economic condition. For example, suppose a person’s income increases two-fold and the price level also rises two-fold. As a result of this upward movement of the price level, the economic condition of that person does not change, i.e., in spite of an increase in his income, his economic condition remains the same.

Thus, real income depends on money income on the one hand and on price level, on the other. During the last five years, money incomes of most of us have increased no doubt, but due to a general rise in the price level, our economic condition has not improved, and in some cases it has deteriorated.

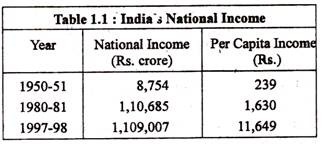

National Income:

The importance of national income accounting stems from the importance of keeping the track of nation’s economic growth. This social accounting attempts to present a comprehensive picture of the working of an economy, showing how the inhabitants earn their income, how they spend it and what they produce.

National income accounting is crucial to economic planning and the formulation and appraisal of policies, and is of use in the construction of a fair and equitable tax system and the development of social and welfare services suited to the needs of the country concerned.

What is National Income?

Goods are produced by men working on natural resources with the aid of machines and tools. Thus, the agriculturist produces rice, wheat and other crops by cultivating land with the aid of seeds, manure, ploughs, etc. The manufacturer produces various articles with the aid of labour, capital and other factors of, production.

By personal effort many kinds of services are produced, e.g., those of the doctor, lawyer, artist, etc. Traders produce utilities by arranging for the sale of goods, Transport workers move goods from one place to another and thereby add values. The result of all these activities appears in the form of a flow of goods and services.

These goods and services are available to the people of the country for use and enjoyment. The aggregate amount of goods and services that is produced in a country during a certain period of time is called its national income. It is also possible to define the term in two other ways.

They are described below:

The goods and services produced in a country ultimately reach the hands of the people producing them in the form of income. Let us take the example of production in factory. Production necessitates the use of four factors labour, land, capital, and organisation. Labourers must be employed, and appropriate site must be chosen for the location of the factory. Capital is also to be obtained.

The three factors — land, labour, and capital — must be organised and managed by business leaders or entrepreneurs who must also bear the risks of production. The earnings of the factory, as a result of production, must necessarily be divided into four parts the labours will get wages, the landlords rent, the owners of capital interest, and the entrepreneurs profits — the residual. Thus, through all kinds of productive activities in the country, people are earning incomes in the form of wages, rent, interest, and profits. The sum-total of such incomes is the aggregate income of the country, i.e., its national income’.

Table 1.1 gives India’s national and per capita income figures for selected years:

Incomes received by the people are partly consumed and partly saved. In other words, a part of the goods and services produced is consumed and a part is used for the purpose of building new machines and equipment of repairing the existing ones. If we add the total amount consumed to the total amount saved, the aggregate must be equal to the national income.

The foregoing discussion makes it clear that the national income can be viewed from three angles:

(1) It can be regarded as the sum-total of the national products.

(2) It can be regarded as the aggregate of incomes received.

(3) It can be regarded as the aggregate of the national outlays on consumption and saving.

6. Production:

At the root of the economic efforts lies the urge to satisfy wants. Nature has endowed us with many gifts. In some cases, these gifts of Nature satisfy our wants directly. Thus, we consume sunlight and air directly. But in most cases, the gifts of Nature cannot satisfy our wants directly.

We require food, furniture, houses, transport, books and various other goods for the satisfaction of our wants. Nature does not give us those goods directly. The art of production is necessary to make these goods available for use and enjoyment. Man satisfies his wants by transforming natural gifts into economically useful goods. Nature has given trees and plants in the forests. Man gets wood from the forest and makes furniture out of it.

Again, Nature has endowed men with many rivers. Man, by applying his energy and skill, constructs dams and uses the water for the production of hydro-electricity and for irrigation. Nature has supplied land. Man, by his efforts, produces food and other crops from land. So production means the creation of useful things, i.e., things having utility. Production can, therefore, be defined as the creation of utility.

Creation of Utility:

Almost all economic goods have to be produced. By production we mean “any activity which adds utility to an object intended for exchange. Production involves the bringing together of resources or factors, like land, labour, capital and entrepreneurship. The keeper of a shoe-store is engaged in the production of shoes, he does not make shoes, but he adds to their utility for the consumer. He orders them from the wholesaler or manufacturer, unpacks them, and puts them on the shelves. He fits the shoes on the customer, wraps them, and perhaps also delivers them to the customer’s door.”

Working around the houses adds to the utility on one’s dwelling. But such activity is not to be treated as production if the purpose is to improve the house for the owner’s personal satisfaction and not to raise the price of the house at a sale. Similarly, the work of a housewife is not production because it does not relate to exchange and price. But if a housewife’s work is done by a hired maid it is to be classified as production.

Here we are concerned only in the economic aspects of production. The concepts stand only for the nature of the combination of the services of resources which adds to the utility of an object.

Sometimes the word production is used to mean the creation of new things. This is, however, a mistaken idea. Man cannot create any new things. He only creates desiredness or utility in the free gifts of Nature and in that way tries to satisfy his wants. Thus, by cutting a tree, a man gets wood and out of it he may manufacture chairs, tables, etc. In this case, he is only increasing the desiredness or utility of the tree and the prices of wood. Man cannot create matter or destroy matter.

Again, some are of opinion that if the creation of utility does not assume any material form, it cannot be called production. According to this view, those who produce various material goods like clothes, houses, wood, furniture, and other professionals, are the productive workers, but teachers, musicians, doctors, judges, actors, etc. are unproductive workers because their services do not assume any material form. The services of the latter groups of people are consumed simultaneously with production. But any labour, which produces goods and services, i.e. creates utility, must be called productive labour.

The division between goods and services is not always to make, nor is it always useful. It is difficult to think of a community which does not have any services attached to it. If we take a commodity and see how its final selling price is fixed, the interdependence of ‘productive’ and ‘non-productive’ workers will become clear.

The coal mined by miners at the pithead has almost no use; it must be transported to industrial and domestic consumers to make it useful or to create its utility (and the carrying cost thus enters the final selling price of coal). Coal merchants acting as distributors must also take a ‘margin’ and that too will form a part of the final price.

None is unimportant in the whole process, and it is necessary, therefore, to include those activities into production which are not physically concerned with making the goods. For this reason, economists use the word ‘production’ in a broader sense in order to refer to all those economic activities which result in the creation of goods and services to satisfy consumer demand.

In short, creation of utility in any form is called production. This creation of utility may assume the form either of material goods or of services. We have already learnt that man many create different forms of utility, i.e., form utility, place utility, time utility, and service utility. Creation of utility in any of these forms should be called production.

The main characteristic of modern-day production process is specialisation by product and division of labour. Unlike the situation of England in manorial system or old village setup in India and other countries, very few people now individually produce all the goods and services they consume. Division of labour is a further step from specialisation by products, where specialisation by process is being sought to achieve maximum productive efficiency.

7. Factors of Production:

The various agencies which collaborate in the processes of production are called factors of production, productive services, inputs, productive resources, or simply resources or factors. These are grouped into four broad categories land, labour, capital, and organisation (or entrepreneur ship).

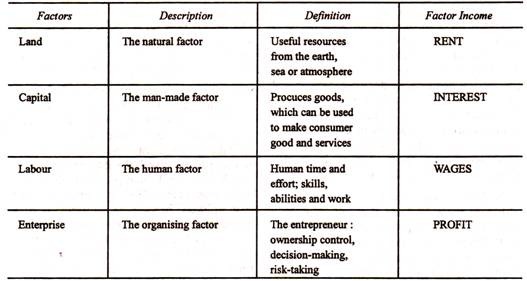

The way in which economists classify scarce resources is shown in Table 1.2:

Table 1.2: Scare Resources: The factors of Production:

For convenience, they can be classified under four headings. The production of any good or service is certain to use up at least some of each of these four factors; in other words there is a ‘factor cost’.

Land refers to all natural resources. Labour designates all human efforts, physical or mental, exerted for a compensation. Capital stands for man-made objects designed to aid the other factors in producing goods and services. The office building of a company, the taxicab, machinery, and raw materials are all capital. The entrepreneur is, briefly, the businessman, who organizes the productive processes and assumes the risks associated with modern business.

8. The Firm:

The entrepreneur is identified with the firm. The firm is an organization for the purpose of producing and selling one or more articles for profit. The firm is a unit of production engaged in one or several productive processes; it is symbolized by and presided over by one responsible management at the top. A firm may operate in more than one plant.

9. The Household:

The firm sells goods and services; the consumer buys goods and services. The term consumer is not confined to a single person but extends to the consuming unit, the household. A housewife makes the choice for the family when buying groceries and other articles. Household sometimes embraces only one individual, as in the case of a bachelor who makes his own purchases.

While the firms are the centres of decision with respect to production, the households, are the centers of decision with respect to consumption. The firms are related to supply of unfinished and finished goods; the households form the demand for finished goods.

The firms produce for the households; the households labour and invest for the firms. The firms have a demand for the factor-services. For their productive services the households receive money income from the firms. They spend the income, partly or fully, on purchasing the consumption products made by the firms.

10. Consumption:

Production is thus the creation of utility, consumption is the converse of it, i.e., the destruction of utility for the satisfaction of a human want. We can neither create nor destroy things of Nature; we can only create and destroy their utility. A simple example will illustrate this. We purchase or manufacture a chair for sitting. Then we begin to use it.

Through constant use the chair gets worn out and is then turned into a few pieces of wood. At that stage, what remains of the chair cannot satisfy our want for sitting accommodation. In other words, through constant use, the utility of the chair has been destroyed but the matter originally contained in it (the wood, etc.) still remains. In the same way, dresses get worn out through constant use. We can say that the chair or the dress has been consumed.

11. Human Wants:

Persons are born with certain basic desires, such as: for food, for warmth, for security. The choices which a person makes of particular goods to satisfy these wants, however, are largely determined by the customs of the society in which the person lives. Some ways of satisfying wants are socially (and legally) acceptable; others are not.

A person has a basic desire to avoid the discomfort of extreme cold; but the type of clothing which he wears is likely to be dictated, largely by the customs of the community to which he belongs. Likewise, a person has a basic desire to obtain recognition from his fellow persons; but depending on the society in which he lives recognition may be determined by the number of degrees he acquires, the size of the house he builds, or the extent of the business house he controls.

The demand for goods and services arises from human wants. People have many wants and require all sorts of goods and services for satisfying them.

Features of Human Wants:

There are certain characteristic features of human wants.

They are explained below:

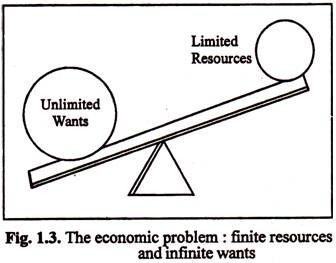

a. Wants in general are unlimited in number:

It is impossible to satisfy human wants because as one economic want is satisfied another appear on the scene. This may be compared to a see-saw with, on the one hand, the limited resources of the world while on the other hand with unlimited wants (see Fig. 1.3).

It may be possible to satisfy human needs, so that we could say, for example, a person needs three trousers, two pairs of shoes, sufficient health care, etc., but this is not the same thing as human wants. If we give people enough to eat then they may want better or different foods; if we give them enough to wear then they want more costly dresses and so on. Thus, in this sense, the economic problem is insoluble.

b. Though wants in general are unlimited, a particular want is limited:

The desire of a particular thing, a shirt or a chair or a table, is limited. A thirsty man wants a glass of water very urgently. But after he drinks a glass of water his want of water will be more or less satisfied and he will not want another glass as urgently as before. This fact is indicated by saying that each particular want is satiable, i.e., can be satisfied.

c. Wants are competitive:

The desire for a hot drink may be satisfied by tea or coffee. The desire for dress may be satisfied by a dhoti or by a pair of trousers. We can say that a choice has to be made between tea or coffee and dhoti or trousers. The wants for these things are competitive.

d. Some wants are complementary:

The desire for drinking tea can be satisfied only by the use of milk, sugar and tea. To drive a motor car it is necessary to have petrol. The wants of things which must be used together are described as complementary.

Classification of Wants:

Want, or rather the goods and services needed for the satisfaction of human wants, can be classified into three main types necessaries, comforts and luxuries.

By the term necessaries we mean goods and services which are of urgent need to human beings. Necessaries again are of two kinds, necessaries for life and necessaries for efficiency. The former includes things without which human life is impossible, e.g., food, water, coarse clothing, etc. The latter includes things which are needed for making people efficient workers, e.g., nutritious food, a good place to live in, good clothing, etc.

There are certain articles which by custom and habit are regarded as absolutely essential by most people, though they are not needed either for maintaining life or for efficiency. These are things like betel-nut, cigarettes, etc. which people are accustomed to use. Very often we find people willing to give up the essentials of life, like food, for the sake of having cigarettes. These things are called conventional necessaries.

The term comforts is used to denote goods which are not absolutely essential but which enable people to lead an enjoyable life. A fine dhoti is not needed for maintaining bare life or for working efficiently. But a fine dhoti gives comfort and makes life enjoyable. Such articles are called comforts.

The term luxuries includes goods and services which are neither necessaries nor required for comfortable living. A shirt made of ordinary cloth is a necessity; a shirt made of fine cloth is a comfort; a silk shirt is a luxury. Certain luxuries are harmful, e.g., wine. Some are harmless, e.g., a silk shirt.

The consumption of harmful luxuries is quite unjustified. But the consumption of harmless luxuries can be justified on many grounds. Firstly, it makes life pleasant. Secondly, the production of such articles gives employment to a large number of people. Thirdly, the desire to have luxuries makes men work hard. Therefore, the national output is increased.

It is important to remember that an article may be necessary to some people while it is comfort to some other and luxury to a third group. For example, a motor car is a necessity to a doctor, but comfort to a college teacher, and a luxury to an office assistant.

Again, woollen garments are necessaries in cold climates, but in warm ones they are either comforts or luxuries. Thus, the classification of consumption goods into necessaries, comforts, and luxuries is relative to time, place and circumstances of the individual.

12. Standard of Living:

It is useful to begin any study of Economics by asking what may be meant by the ‘standard of living’ in a country, e.g., concern about the measurement and determinants of growth in the material standard of living of a country as a whole marks the beginning of modern economics.

If people were asked what they thought the government’s main economic objective should be, the most common reply would probably be ‘to improve the standard of living’. If they were then asked to define what they meant by an improved standard of living, many would no doubt talk about an increase in consumption or an increase in real income. So the concept of consumption is closely associated with that of ‘standard of living’, by which we refer to the aims and directions of our consumption.

We always want better things—better housing, better clothing, better educational facility for our children, better recreational arrangements and so on. Very often we do not get many of the things we aim at. But the things we really miss—which we consider to be the aim of our consumption—constitute what is called ‘standard of living’. In other words, the term ‘standard of living’ is used to denote the pattern of consumption which a society or different social groups enjoy for long.

Since societies or social groups widely differ from one another, standard of living also varies. For instance, an American farm worker has different standard of living—the pattern of consumption aimed at—from that of an Indian farm worker. Secondly, standard of living is relative to time as well. Electricity is an essential part of life today, but there was time when a kerosene lamp was adequate for lighting purposes.

A distinction must be made between ‘standard of living’ and ‘level of living’. The former consists of those material goods and services or wants that an individual or the community strives to attain. But the latter consists of the satisfactions of those wants that an individual or a community actually attains. In other words, the standard of living refers to the aim of satisfaction—the desired things which should be there.

It is true that the standard of living of an individual or household depends on the level of income and wealth. A man having large income and wealth may have higher standard of living. However, if this man has a large number of dependents he may have lower standard of living than one expects. No doubt, income and wealth are the two major determinants of an individual’s standard of living. But from the whole economy’s point of view, one must judge standard of living from the angle of per capita income as well as the distribution of national income.

High per capita income countries are described as developed countries. Standards of living of people of these countries are high. But there are some countries in the world—such as Kuwait—whose per capita income is the highest in the world. Yet most people are poor there. Or, their standards of living are low.

This paradoxical situation has arisen due to the gross inequality in income distribution in those countries. So, we can conclude that income distribution is another important indicator of standard of living. Thus, the ‘level of living’ may be lower than the standard of living. And this is normally the case with less developed countries like our own. But consumption is directly related to both.

13. Equilibrium:

Equilibrium means that a position has been reached—by the individual, the firm, or the industry—in which there is no incentive to change the position is one of rest. The consumer is said to be in equilibrium when he cannot increase his total utility by a change in the allocation of his total expenditure among his purchases.

A firm is in equilibrium when it cannot raise its profit fully by changing its output or by changing the technique of its production. An industry is in equilibrium when there is no incentive for firms to leave it and for new firm’s to enter it. A factor of production is in equilibrium when at the current compensation there is no incentive for it to offer more or less of its productive service.

As M. Bober has put it: “When we examine the forces which tend to determine the price of a ton of steel we are assuming rational behaviour, that is, the search for maximum profit by the selling firm. When the analysis defines the elements which govern the price it indicates thereby the price which gives the firm the greatest profit. Once such a price is established the firm will have no inducement to change it cannot do better than to maximize its profit. The price of steel as finally shaped by the relevant determinants is accordingly an equilibrium price.”

Thus, whenever we investigate the determinants of a magnitude—utility, price, or wage rate— which maximize the return to the consumer, to the firm, or to the factors of production, we are trying to find out the conditions of equilibrium of this magnitude. The analysis of price becomes the analysis of price equilibrium, that is, of a price which offers no inducement to the agent concerned with it to institute a change.

In actual life, the state of equilibrium is seldom reached; the reason is that economic life undergoes continual change. In every segment of the economy there are ceaseless movements and tendencies toward equilibrium, but rarely the attainment of it.

14. Value and Price:

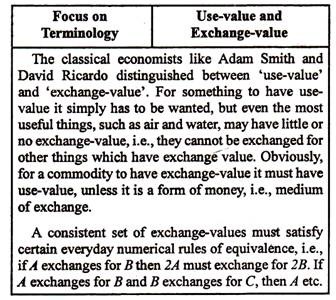

Usually, value and price are used interchangeably. But in economics, the word value is used generally in two different senses value-in-use and value-in-exchange. By value-in-use we mean utility or the capacity to satisfy wants. In this sense, value means utility. We say that water is valuable for human life. This means that water has great utility. Water satisfies a basic human want.

Secondly, the word is also used to mean value-in-exchange. Value-in-exchange of a commodity is the rate at which it is exchanged for other commodities. Thus, if for one quintal of rice two quintals of wheat can be obtained, the value of one quintal of rice is two quintals of wheat. In Economics, the word value is used generally to mean value- in-exchange, and value-in-use is denoted by the term utility.

It does not necessarily follow that a certain commodity which is a high value-in-use must also have a high value-in-exchange. Water, for example, has a high value-in-use but in most cases, it has no value-in-exchange. A high value-in-use combined with scarcity and transferability will result in a high value-in- exchange for a commodity.

On the other hand, price is exchange value expressed in terms of money. Thus, when we say that the price of a motor car is Rs. 82,000 then what we mean is that Rs. 82,000 can be exchanged to by one car. Thus, price is expressed in terms of money. It is not used in relative sense. On the other hand, the term value is used in relative sense. For instance, the (exchange) value of one economics book is two fountain pens.

Now, if one economics book is exchanged for one pen then it can be said that the value of the book has gone down while that of the pen has increased. On the other hand, the price of both the book and the pen may rise at the same time. So all prices may rise or fall together, but not all values (i.e., the exchange values).

If the prices of all things rise, this means that their value in terms of money has gone up, i.e., the value of money has gone down in terms of commodities. Usually, during inflation, prices of all commodities increase, but the values do not; since value of a commodity is expressed in terms of another commodity.

Finally, it must be borne in mind that the concept of value is a generalised one than price.

15. Opportunity Cost:

Once the decision has been made to use some resources to satisfy one particular want, it cannot be used to satisfy any further wants. If the wood from a tree is pulped to make paper then it cannot be used to manufacture furniture. If a teenager uses birthday money to buy a record then she cannot use it to buy a story book. If Calcutta Municipal Corporation uses Rs. 1 crore to build a sports centre that money cannot be used to build an old people’s home.

Thus, sacrifice is always involved in choosing to use scarce resources to produce one commodity rather than another—for example certain amounts of land, labour and capital that could have made 20 scooters might be used to make one car. The sacrifice in making the car would then be 20 scooters.

Economists call these lost alternatives the opportunity cost of using the resources. Opportunity cost (sometimes called economic cost or real cost), measures the cost of something in terms of the sacrifice of the next best alternative.

Underlying business decisions is the fact that resources are scarce. This scarcity can be reflected in various ways, such as shortages of capital, physical and human resources, and time. The existence of scarcity means that whenever a decision or choice is made, a cost is incurred. Economists take a broader view of such a cost than that based purely on monetary factors as used by accountants. In economists jargon, such costs include opportunity cost.

The opportunity cost of an activity is the loss of the opportunity to pursue the most attractive alternative given the same time and resources.

Any firm with its available factors of production (which may be broadly categorised as land, labour and capital) has a choice as to the products it may produce.

16. Marginal Analysis:

The idea of opportunity cost highlights that choices have to be made regarding what to produce. The concept of the margin reminds us that most of these choices involve relatively small (incremental) increases or decreases in production. For example, decisions have to be made regarding whether to provide an extra production shift, to generate an extra megawatt of electricity, to produce 1,000 fewer ball-bearings, to add a product to the product range, etc.

Only relatively rarely do we make decisions about all or nothing, e.g., whether to be a manufacturer or not. The scale of the increase or decrease on production — the extent of the ‘marginal’ change — will, of course, be related to the scale of the overall operation. For example, electricity generating companies are most unlikely to be concerned with decisions about whether/or not to produce one more watt of electricity!

The concept of the margin is central to most economic decisions both in terms of consumer behaviour when buying products and the behaviour of firms when deciding whether to alter production. Consumers, through their purchasing decisions, must decide whether or not buying a particular product will add more to their well-being than spending the same amount on some alternative.

Similarly, at the heart of business decision-making is the question of whether or not the increase in output will provide enough extra revenue to compensate for the extra cost of production. The aim of the manager (i.e. the decision-maker in this case) is to find the optimal level of production.

Opportunity cost is measured in physical, not monetary, units. Indeed, it is sometimes called real opportunity cost to distinguish it from money cost.

Moreover, opportunity cost normally involves giving up some positive amount of one commodity in order to get more of another. So this cost is almost always positive. It is positive with economic goods. Normally, the production of one commodity necessitates giving up some positive amount of some other commodity. However, it can be zero in case of free-goods and single-use factors (i.e. factors having no alternative uses).

17. Time Dimension:

Business decisions and objectives need to be considered within a time framework— profit maximization in the short term may not be consistent with the long-term success of the company. In certain circumstances it may even lead to the downfall of the company in the long term.

For example, short-term profit maximization might mean that workers are pushed so hard to increase production for relatively low wages that they eventually go on strike, or that goods are made which are less reliable and sold at such high prices that new competitors eventually emerge to take over the market. This suggests that profit maximisation can only usefully be discussed in relation to a given time dimension.

Time is a continuum, but for convenience economists normally distinguish between the following two broad time periods, which are referred to as the short run and the long run:

i. The short run represents the operating period of the business in which at least one factor of production is fixed in supply. This means that, for example, as the firm attempts to increase output by employing more and more of one resource alongside a fixed resource, diminishing marginal returns set in. For example, employing more and more workers on an existing machine is likely to lead to overcrowding and a reduction in productivity, i.e. output per worker. Ultimately, there will be one level of production in the short run which is the most cost efficient and that can be attained given existing resources.

ii. The long run is the firm’s planning period. In the long run all factors are variable. Moreover in the long run it is possible to change the scale of production of a firm, i.e., its size.