The below mentioned article provides an essay on planning in India (1951 – 1991).

Introduction:

At the time of independence India was a backward underdeveloped country. There was a lot of exploitation of India during the British colonial rule.

This made Indian people very poor. The aim of freedom struggle was not mere gaining political freedom from the British rule but also to attain economic freedom for the Indian people. Economic freedom implies the removal of mass poverty that prevailed in India.

At the time of independence there was deficiency of good entrepreneurs who could use the natural resource endowment of India for economic development. To improve living standards of the people, it was necessary to accelerate rate of economic growth. It was thought that the private sector lacked the necessary resources and the proper mindset to bring about rapid economic growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Inspired by the Russian experience, planning as an instrument of economic development was adopted. The Planning Commission was set up to prepare five year plans which would indicate directions in which the Indian economy should move. Resources were to be allocated both at the Centre and in the States according to the plan priorities decided in a five year plan.

The basic objective of Indian planning has been acceleration of economic growth so as to raise the living standards of the people. Further, various five year plans also gave high priority to generation of employment opportunities and removal of poverty. In what follows we will explain the role of planning in India and then explain the development strategies adopted in various plans to achieve the objectives.

Role of Planning In India:

Accelerating Economic Growth:

There were two main features of India’s economic policy that emphasized the role of planning and intervention by the State in the development process of the Indian economy in the first three decades of planning. First, to accelerate economic growth economists and planners recognized that raising the rate of saving and investment was essential to accelerate the rate of economic growth.

It was thought that the private sector on its own would not be able to achieve a higher rate of saving and investment required to break the vicious circle of poverty. Therefore, the state had to intervene to raise resources and increase the rate of saving and investment. This made the planning and the expansion of the public sector essential to accelerate economic growth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Emphasis on Industrialisation, Second, the strategy of development, adopted since the adoption of Second Five Year Plan which was based on Mahalanobis growth model, laid stress on the industrialisation with an emphasis on the development of basic heavy industries and capital goods industries.

This model implied allocating a higher proportion of investible resources to capital goods industries than to consumer goods industries. Private sector which is driven by profit motive could not be expected to allocate sufficient resources to the growth of capital goods industries.

Therefore, the role of planning and the public sector was considered essential for rapid growth of basic heavy industries. Mahalanobis growth model was wrong in neglecting the role of agriculture and importance of wage goods for accelerating growth of output and employment. In fact, shortage of food, a cheap wage good, rather than machines could act as a constraint on the growth process. This became evident by the time of the Third Plan which laid a relatively greater stress on growth of agriculture to achieve self-reliance.

But rapid growth of agriculture itself requires a good deal of state intervention and planning. The land reforms in agriculture, supply of adequate credit to farmers, development of infrastructure such as irrigation, power, roads were necessary where planning and State could play an important role.

To Compensate for Market Failures:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The dominant view in development economics in the fifties and sixties also laid stress on the planning by the State to compensate for ‘market failures’. It was argued that while market mechanism was efficient in distributing a given stock of available goods, it was quite inefficient in allocating resources over time for investment.

This was because of myopic nature of private sector which guided the working of markets. It was therefore asserted that the State and planning could play an important role in allocating resources for investment to bring about rapid economic growth.

Besides, failures of market mechanism and free working of private sector to allocate adequate amount of resources for investment in infrastructure such as power, transport, communication created substantial external economies and also where significant economies of scale existed. Therefore, in the development of infrastructure, the State and planning had an important role to play.

Regulatory Role of the State:

There is another important aspect of the role of State and planning in the development of the Indian economy which dominated economic thinking in the pre-reform period. Though the private sector was given an important role to play in the framework of mixed economy, to achieve optimal allocation of resources among different industries according to plan priorities, economic activities in the private sector were required to be regulated by the State. Further, to achieve other objectives of planning such as restraining the concentration of economic power in a few big business houses, the private sector was subjected to industrial licensing controls.

To quote C. Rangarajan, the former Governor of the Reserve Bank of India, “while the private sector was given space to operate in keeping with the concept of a mixed economy, in the field of industry particularly the decisions of the private sector were circumscribed by the licensing mechanism. Hence, while foreign trade was subject to control because of the strategy of import substitution, industrial production and investment were subject to control because of the need to direct resources according to plan priorities”.

Tackling the Problems of Poverty and Unemployment:

The other problem which makes role of planning and state intervention important is the need to tackle the problems of poverty and unemployment. Since the beginning of the seventies the Indian planners realised, especially in the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Five Year Plans, that even if growth rate of GDP was raised to 5 to 6 per cent per annum, it was not possible to make a significant dent on the problems of mass poverty and unemployment prevailing in the Indian economy.

Some argued that benefits of economic growth did not trickle down to the poor. Others were of the view that even if the poor get benefits from growth by way of more employment opportunities generated by it, mere economic growth was not enough to eradicate poverty and unemployment. Therefore, role of planning and State was necessary to start and implement special poverty and unemployment schemes such as Food for Work Programme and Employment Guarantee Schemes to help the poor and weaker sections of the society.

Development Strategy in India’s Five Year Plans:

In the Second Five Year Plan strategy which continued practically till the Fourth Plan period (1969-74) it was visualized that basic constraints on development was the acute deficiency of physical capital which was responsible for small productive capacity of the Indian economy. It was further thought that the rate of capital formation depended on the domestic rate of saving which could be raised by the adoption of proper fiscal and monetary policies.

However, Mahalanobis, author the Second Plan’s development strategy, asserted that even if domestic rate of saving could be increased, the non-availability of the domestic capacity to produce capital goods would prevent the transformation of these savings into real productive investment. Note that real investment occurs when savings are spent on purchasing capital goods such as machinery and equipment. The alternative to the expansion of domestic capacity to produce capital goods would be importing capital goods to ensure sustained increase in the rate of real investment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Mahalanobis ruled out import of capital goods on grounds of lack of foreign exchange earnings from exports. He argued that if large investment was not made in basic heavy industries producing capital goods, the country would ever remain dependent on foreign countries for the import of steel and capital goods.

Since it was not possible for India to earn sufficient foreign exchange by increasing exports, the capital goods could not be imported in sufficient quantities owing to foreign exchange constraint. The result will be that the rate of real capital formation and rate of economic growth in the country would remain low.

Thus, Mahalanobis was of the opinion that without adequate investment in basic heavy industries, it would not be possible to achieve rapid self-reliant economic growth. According to Mahalanobis, “The proper strategy would be to bring about a rapid development of the industries producing investment goods in the beginning by increasing appreciably the proportion of investment in basic heavy industries. As the capacity to manufacture both heavy and light machinery and other capital goods increases, the capacity to invest in home produced capital goods would also increase steadily and India would become more and more independent of imports of foreign machinery and capital.”

Further, according to Mahalanobis, productive employment can be created only by increasing the production of capital goods. To quote him, “the only way of eliminating unemployment in India is to build up a sufficiently large stock of capital which will enable all unemployed persons being absorbed in productive activity. Increasing the rate of investment is therefore the only fundamental remedy for unemployment in India.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Another important element of development strategy adopted in India’s earlier Five Year Plans was their emphasis on modem industrialisation, especially of import-substitution type. It was generally believed that industrialisation would generate sufficient employment opportunities which would cause surplus labour currently unemployed in agriculture to be shifted to more productive employment in industries. The underlying assumption was that agriculture was subject to diminishing returns and could not absorb unemployed labour productively whereas industries operated according to increasing returns to scale.

Thus, identifying underdevelopment with dependence on agriculture and thinking industrial growth especially the development of heavy industries as the core of development underlined the approach and strategy of the Second Five Year Plan.

To quote from Second Plan again, “low or static standards of living, underemployment and unemployment, and to a certain extent even the gap between the average income and the highest income are all manifestations of the basic underdevelopment which characterizes an economy depending mainly on agriculture. Rapid industrialisation and diversification of the economy is thus the core of development. But if industrialisation is to be rapid enough, the country must aim at developing basic industries and industries which make machines to make the machines needed for further development.”

It is clear from above that in the Second Plan there was a clear shift of priorities from agriculture to industries and within industries to basic heavy industries. The logic of Mahalanobis in emphasizing heavy industries was that the growth of basic heavy industries would enable the economy to accelerate the rate of capital formation and therefore economic growth. In fact, he identified the rate of growth of investment in the economy with the rate of growth of output in the capital goods sector of the economy.

Mahalanobis’ Four-Sector Growth Model and Employment Generation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Mahalanobis realised that the basic heavy industries being capital-intensive would not ensure rapid expansion of employment opportunities and to bring the employment aspect into sharp focus he put forward a four-sector growth model in which he kept heavy industry sector (i.e. K-sector) intact but divided the C-sector (i.e. consumption goods sector) into three sub-sectors : C1, C2, and C3 (sector C1 represented factory enterprises using mechanized techniques and producing consumer goods; sector C2 represented the household and small-scale enterprises also producing consumer goods, and sector C3 represented provision of services).

It was sector C2 representing households and small-scale industries which in Mahalanobis’ four-sector model was visualized to ensure the increased supply of consumer goods to meet the rising demand for them and also to ensure, being labour-intensive, expansion of employment opportunities. In keeping with this approach, Second Five Year Plan put restrictions on the growth of capacity in factory enterprises engaged in commodity production.

However, since for these household or cottage enterprises, adequate resources were not provided, nor any effort was made to improve their productivity, they could neither fulfill their targets of production of consumer goods nor of generating enough employment opportunities.

Vital Role of the Public Sector:

Lastly, the other important element of development strategy pursued in India’s Five Year Plans (which continued up to the end of 1980s) was the vital role given to the public sector in economic development of the Indian economy.

This was based on the assumption that if private sector and market mechanism were relied upon for development of industries there would be more investment in consumer goods industries catering to the needs of upper income groups while adequate investment in the sectors essential for rapid growth of the economy would not be forthcoming.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the Third Plan (1961-66) also the strategy of Second Plan was continued as is clear from the following:

“In the Third Plan, as in the Second, the development of basic industries such as steel, fuel and power and machine building and chemical industries is fundamental to rapid economic growth. These industries largely determine the pace at which the economy can become self-reliant and self-generating.”

Though, “to achieve self-sufficiency in food grains and increase in agricultural production to meet the requirements of industry and exports” was stated to be one of the objectives of the Third Plan, actual allocation of resources between agriculture and other sectors did not exhibit any significant difference from that of the Second Plan. Therefore, the concern for food and agriculture in the Third Plan appears to be mere verbal and was not built into the strategy of development.

The Fourth Five Year Plan (1969-74) which was prepared under the Deputy Chairmanship of Late Prof. D.R. Gadgil, tried to give a new shape to the planning strategy and emphasis was sought to be placed on the common man, the weaker sections and the less privileged. The Fourth Plan slightly raised the allocation of public sector outlay to agriculture and irrigation to about 23 per cent as against 20 per cent in the Second Plan and the Third Plan. However, a good deal of hangover of the heavy industry biased strategy still prevailed in this plan too.

Thus, the development strategy pursued till the end of the Third Plan was growth-oriented, though objectives of increasing employment and reducing income inequalities were mentioned but never seriously pursued and implemented. However, the situation changed dramatically in the mid- sixties.

The two wars, one with China in 1962 and the second with Pakistan in 1965, compelled us to increase defence expenditure. During this time foreign aid situation also became un-favourable resulting in foreign exchange crisis. The devaluation of rupee in June 1966 also did not improve the foreign exchange situation. The situation became more grim with the successive two droughts that hit the country in 1966 and 1967.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Worsening economic situation and growing concerns for national security highlighted the two shortcomings of the development strategy adopted in the Second and Third Five Year Plans.

They were:

(1) Relative neglect of agriculture resulting in the acute food problem for the country,

(2) Crucial dependence on foreign aid which could not be relied upon for accelerating growth in the future plans.

This highlighted the importance of pursuing the objective of self-reliance which implied reducing the dependence on foreign aid.

In the later half of the sixties, resource situation for the public sector became difficult and uncertain. This resulted in the suspension of planning for three-year period (1966-69). This three- year period (1966-69) is therefore called period of plan holiday. Due to non-availability of adequate funds, public sector investment was reduced from the mid-sixties onwards.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, in the 4th Five Year Plan resource allocation to agriculture was increased to achieve self- sufficiency in food grains. Besides, new strategy of agricultural development, initiated earlier in 1966- 67, was pursued more vigorously during the Fourth Plan period. The new strategy of agricultural development which involved the use of high-yielding varieties (HYV) of seeds, fertilizers, pesticides with appropriate quantity of water was introduced in a few selected districts of the country where assured irrigation facilities were available.

Second, in the Fourth Plan relatively more importance was given to export promotion than before along with the policy of import substitution which was continued. Though the new agricultural development strategy proved to be successful and production of food grains, especially wheat, grew at a satisfactory rate, the growth scenario remained dim due to slackening of public sector investment which started in the mid-sixties and continued up till mid-seventies. Average growth in net national product (NNP) achieved during the Fourth Plan was only 3.3 per cent per annum.

As a result of cutback in public investment, problem of deficiency of aggregate demand emerged which resulted in slowing down of industrial growth during 1966 to 1978-79. It is important to note that in first four Five Year Plans of India it was never visualized that in the Indian economy level of aggregate demand could possibly be a constraint on the growth process.

Development Strategies in the Fifth, Sixth and Seventh Plans:

Besides, in the early seventies, it was realised that growth-oriented development strategy adopted in the first over two decades of planned development (1951-74) had not succeeded in alleviating poverty. Statistical evidence revealed that about 321 million people lived below the poverty line in 1973-74 and unemployment problem was mounting.

At this time political situation in the country became uncertain with Congress party losing election in some States. Further, while preparing the 5th Five Year Plan it was recognized that trickle down effect of economic growth on the poor and unemployed was not working. Thus, in “Towards an Approach to Fifth Five Year Plan” it was stated that “Economic growth by itself would not lead to the solution of the problem of poverty and unemployment in the foreseeable future”.

Therefore, Fifth Plan formulated a programme of making a ‘direct attack on poverty’ which visualized special employment such as Jawahar Rozgar Yojana, for providing wage employment to the poor, IRDP (Integrated Rural Development Programme) for providing self-employment to the poor. Except for these anti-poverty schemes Firth Plan was not much different from the earlier Five Year Plans. These anti-poverty schemes were merely added to the Fifth Five Year Plan without integrating them with the growth programmes.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But while formulating Fifth Plan (1974-79) the new Planning Minister, Mr. D.P. Dhar, took charge of preparing the final draft. According to the Approach to Fifth Plan on which the final draft was made, “The strategy for elimination of poverty… rested on two major factors, a rising rate of growth of domestic product combined with declining rate of population growth”.

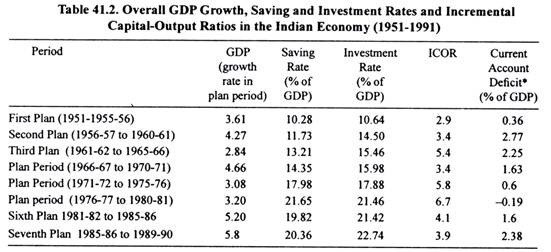

This latter approach was indeed a combination of old planning strategy with emphasis on economic growth though increase in employment was considered to be a desirable objective. Thus employment-orientation was not actually given to the planning strategy in the Fifth Five Year Plan. For achieving a higher rate of economic growth Fifth Plan draft was also based on a wrong assumption of incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR) of 3.4 whereas in the previous plan it was actually found to be equal to 4.3.

However, during the period of Fifth Plan (1974-79), the emergency was declared in the country and Prime Minister’s 20-Point Programme was given more importance over the implementation of Fifth Plan projects and policies. The Fifth Plan could not be completed as in March 1977, Janata Government came to power and terminated the Fifth Plan in March 1978.

The Sixth Five Year Plan (1980-85):

It may be noted that there were two Sixth Five Year Plans. One Sixth Five Year Plan for the period (1978-83) was prepared by Janata Government but it could not be completed as Janata government collapsed and failed to win the new election held in Dec. 1979. The Congress Government again came to power in 1980 and formulated new Sixth Five Year Plan for the period 1980-85.

The development strategy of Sixth Plan (1980-85) laid emphasis on promotion of efficiency in resource use and improvement in productivity to achieve 5.2 per cent growth in GDP. Besides, the infrastructure sector was given the topmost priority in the allocation of resources. Further, in the Sixth Plan employment generation and poverty eradication were given high priority.

In this additional employment opportunities for 46 million persons were planned to be generated during the plan period through IRDS (Integrated Rural Development Scheme), NREP (National Rural Employment Programme) and RLEP (Rural Landless Employment Programme) schemes. The Sixth Plan aimed at reducing the percentage of people below the poverty line to 30 per cent of population.

The infrastructure sector was given the topmost priority in the development strategy of the Sixth Plan whereas, like the earlier plans, agriculture rural development, and special employment programme received allocation of about 13 per cent of total outlay.

The Seventh Plan (1985-90) Strategy:

The Seventh Plan’s strategy of development was to improve the utilisation of existing productive capacities rather than creating new capacities. It sought to secure more output out of productive assets that had been built up in the previous years. Besides, the plan strategy laid emphasis on a direct attack on the problems of poverty and unemployment by providing a greater outlay on special employment schemes rather than relying on ‘trickle -down’ effect of economic growth.

The other important aspect of development strategy of the Seventh Plan was that it planned for a non-inflationary growth process by laying greater emphases on the production and supply of mass consumption goods like food grains, edible oils, sugar, cooking fuel and textiles.

Thus, the strategy of development for the Seventh Plan accorded a higher priority to wage goods. Another important change in the policy regime during the Seventh Plan period (1985-90) was that process of liberalisation was initiated.

In the industrial policy resolution of 1956 amendments were made under which licensing procedures were somewhat relaxed and liberalized, and the existing capacities were allowed to be used liberally by diversification through broad-banding. Besides, measures were taken to give greater role to the private sector in economic development.

India’s Economic Performance in the First Four Decades (1951-91) of Development Planning (Pre-Reform Period):

The development strategy pursued in the four decades planning (1951-91) has both successes and failures in achieving the objectives and targets. The Indian economy witnessed a profound structural transformation during this period. We became wholly self-sufficient in food grains and most other agricultural commodities. Food production grew at a rate faster than that of population.

As a result of industrial growth during the first three decades of the Indian industry planning (1950-80) became capable of meeting nearly 100 per cent of our requirements of consumer goods and about 85 per cent of our annual demand for capital goods. The strong base of future industrial growth rate was laid as a result of significant development of basic and heavy industries.

We succeeded in building up a vast reservoir of technical and managerial skills. For three decades, 1951 -81, the average annual growth rate of real GDP was 3.5 per cent against a virtual stagnation in real GDP during the first half of the 20th century. However, as compared to international standards the Indian growth rate in the first three decades was quite low.

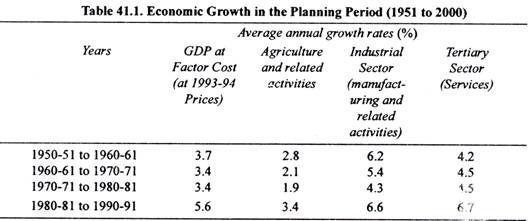

As will be seen from Table 41.1 annual growth rate in GDP was 3.7% during 1951-61,3 .4% during 1961-71 and 1971-81. Further, as is seen from Table 41.1, growth rate in GDP was pulled down in the decades of sixties and seventies is compared to the fifties by slowdown in both industrial and agricultural growth rates.

It may be further noted that there was a significant deceleration in industrial growth rate from mid-sixties to mid-seventies (1965-76) due to decline in public sector investment. With population growing at the rate of 2.25 per cent per annum, per capita income increased at the rate about 1.5 per cent per year during the period (1951-81). However, during the decades of eighties and nineties growth rate in per capita income accelerated due to higher growth in GDP and also due to decline in growth rate of population.

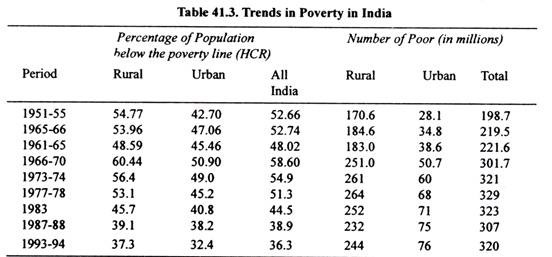

In the first three decades (1951-81) of planned development in India the rate of economic growth was not high enough to make a significant dent on the problem of poverty. The proportion of population with level of consumption below a very modest poverty line fluctuated between 50 and 58 per cent of population during the fifties, sixties and seventies (that is, in the first three decades of planning).

These estimates clearly show that in the first three decades of planning (1951-81) economic growth did not have any impact on the poverty problem in India. This is because of not only slow rate of economic growth during this period but also that benefits of whatever economic growth occurred did not trickle down to the poor. It is only in the eighties and nineties when annual rate of economic growth rate accelerated to around 5.6 per cent and 6 per cent respectively and special employment schemes were started on a large scale that there was a significant decline in the incidence of poverty.

In the eighties of the 20th century, two Five Year Plans, the Sixth Plan (1989-85) and Seventh Plan (1985-90) were launched. In the Sixth Plan period (1980-85) and Seventh Plan period (1985- 90), average annual growth rate of 5.4 per cent and 5.8 per cent respectively was recorded. This higher growth rate in national income also resulted in a higher growth rate in per capita income of 3.2 per cent and 3.6 in the Sixth Plan and Seventh Plan periods respectively.

Favourable result of this higher growth rate in both national income and per capita income was the decline in the ratio of people living below the poverty line. As will be seen from Table 41.3 percentage of population living below the poverty line (All India) which was 51.3 in 1977-78 fell to 44.5 in 1983 and further to 38.9 in 1987-88 and 36.3 in 1993-94.

Now, the question is what caused this acceleration in growth rate in the late seventies and the eighties. The important factor causing this acceleration in growth rate in the late seventies and early eighties was the increase in public sector investment which remained sluggish earlier since the mid-sixties.

Among other factors bringing about higher growth rate is the liberalisation measures of removal of some restrictions and relaxation of licensing procedures by making amendments through industrial policy statements of July 1980 and December 1985. In these industrial policy statements certain changes were made in the industrial licensing policies and procedures which were designed to facilitate capacity expansion in the private sector and create competitive environment.

In the later half of eighties (1985-90), contrary to the Mahalanobis strategy of growth, export promotion was given relatively more importance than import substitution which led to higher growth rates of exports of9.4 percent, 24.1 percent, 15.6 per cent, and 18.9 per cent in 1986-87, 1987-88, 1988-89 and 1989-90 respectively which speeded up the overall growth rate of the Indian economy during the latter half of the eighties.

But, the higher growth rate achieved in the eighties was not sustainable as public sector investment was increased by incurring higher doses of deficit financing leading to higher rates of inflation in the economy and through commercial borrowing on a large scale from abroad which significantly raised external public debt. External public debt servicing consumed a large part of our export earnings. This created foreign exchange crisis in 1990-91 which brought India to the brink of default.

Since capital-intensive technologies were used in the growth process of both industrial and agricultural sectors, the employment opportunities increased but not large enough to absorb even annual growth of labour force in productive employment. As a result, backlog of unemployment went on increasing with each successive Five Year Plan. At the end of Fourth Plan period (1973-74) unemployment was estimated at 9 per cent of labour force on current daily basis.

Trends in Saving and Capital Formation: 1951 to 1991:

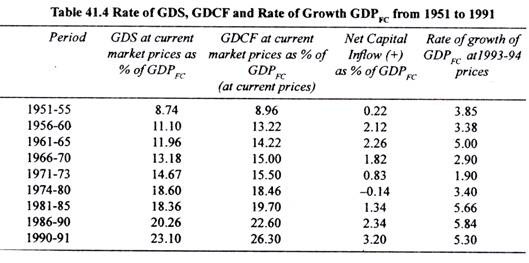

Rates of gross saving and capital formation as a per cent of GDP which are important determinants of economic growth showed upward trends with some fluctuations during the period 1951-80. Both rates increased from around 8 per cent in 1950-51 to 13 per cent in 1955-56, the beginning of the second Five Year Plan.

Thus the two rates remained in balance during this period (see Table 41.4). However, from 1956 to 1965-66, the gap between the two emerged; gross domestic saving (GDS) falling short of gross domestic capital formulation (GDCF). Besides, the two rates fluctuated a good deal during the decade of 1956-1965. The deficit of gross domestic saving and gross domestic capital formation (GDCF), i.e., gross domestic investment during this decade, was met mostly by obtaining concessional foreign assistance with net capital inflow as percentage of GDFC being equal to 2.12 during 1956-60 and 2.26 during 1961-65.

As will be seen from Table 41.4, during the periods 1966-70 and 1971-73, annual rate of gross domestic capital formation (GDCF) increased to 15 per cent of GDP in 1966-70 and to 15.50 per cent of GDP in 1971-73. This was largely financed by domestic saving which increased only little.

The average annual rate of gross domestic saving rose from about 13.2 per cent during 1966-70 to 14.7 per cent during 1971 -73. It is mainly due to stagnation of gross capital formation during 1966-70 and 1971-73 that average annual rate of growth of GDP during this period fell to 2.9 per cent per annum during 1966-70 and 1.9 per cent during 1971-73 (See Table 41.4).

It may be further noted that after war with Pakistan in 1965 on Kashmir issue and then in 1971 on Bangladesh issue, India could not get much foreign aid. As a result, capital inflow during this period declined which also accounted for low rate of capital formation.

From the mid-seventies public sector investment was raised which resulted in higher average rate of capital formation (18.5 per cent of GDP) during 1974-80 and this was fully financed by domestic saving which shot up to 18.6 per cent per annum during this period. In the first half of the eighties, average annual rate of GDCF as per cent of GDP picked up to 19.7 and in the second half (1986-90) of the eighties to 22.6.

As a result, annual average growth rate of GDP rose to 5.6 per cent during 1986-90) and to 5.8 per cent during 1986-90. However, in the second half of the eighties (1986-90) annual rate of gross domestic saving (GDS) as per cent of GDPFC was 20.26 resulting in capital inflow of 2.34 per cent of GDPFC which was mostly in the form of commercial borrowing from abroad. This led to a sharp increase in external foreign debt which put pressure on our balance of payments. In 1990-91, the gap between GDS and GDCF widened and resulted in capital inflow of 3.2 per cent of GDPFC causing foreign exchange crisis.

A Critical Evaluation of Planning in the First Four Decades (1951-91):

The first three decades of planning in India (1951-81) was characterized by lower rate of economic growth at around 3.6 per cent per annum on an average. There are mainly two explanations of this. First, Late Prof Sukhamoy Chakravarty attributed it to the gross inefficiency of public sector enterprises which were given a crucial role in economic development during this plan period.

According to him, there were many areas of public sector production such as transport, steel, fertilizers where gross inefficiency prevailed and this accounted for low productivity and lower growth rate. Further, according to him, in Indian planning adequate growth of aggregate demand was taken for granted and it is due to the decline in aggregate demand caused by decrease in public sector investment from mid-sixties to late seventies that raised incremental capital-output ratio (ICOR) and led to lower growth of output from increase in investment.

It is important to note that it is only from mid-eighties when industrial policy was liberalized somewhat and private sector was given relatively greater role that economic growth rate picked up and overall GDP growth rate of 5.6 per cent was achieved in the decade of 1981-91.

Prof. T. N. Shrinivasan and Prof Suresh Tendulkar attributed lower growth rate in the pre-reform period (i.e., before 1991) to the import-substitution strategy (which is also called inward-oriented strategy) and inadequate attention paid to expanding exports to generate higher growth of output. To quote them, “India s inward-orientation has had significant economic costs to lower overall growth and stagnating living standards. Japan s rapid export growth was associated with very rapid GDP growth and improvement in living standards.”

Further, Srinivasan and Tendulkar hold Mahalanobis’ strategy with its emphasis on basic heavy and capital goods industries and import-substitution industrialisation responsible for lower growth of GDP and the incidence of poverty. Thus they write, “Indian economic performance under this development strategy was poor. For three decades until 1980-81 the average annual rate of growth of real GDP was 3.75 per cent. With the population growing at nearly 2.25 per cent a year income per head grew at about 1.50 per cent. With such a low rate of growth, it is no surprise that there was little reduction in poverty—the proportion of population with consumption below a very modest poverty line fluctuated at around an average of more than 50 per cent. The economy was insulated from world markets—India’s share of world merchandise exports declined from about 2.2 per cent in 1948 to 0.5 per cent in the early eights”.

In contrast to the planning in the first three decades. (1951-80), in the decade of eighties growth rate picked up to 5.6 per cent due to revival of public sector investment and along with expansionary fiscal policy financed by commercial borrowing mainly from abroad which proved to be quite unsustainable as it led to balance of payments crisis of 1991. Explaining this consequence of debt-driven unsustainable consequences of policy of fiscal expansionism Srinivasan and Tendulkar write, “The current account deficit rose to a record 3.2 per cent of GDP in 1990 and debt-service payments amounted to as much as 35.3 per cent of current foreign exchange receipts.” Foreign exchange reserves were down to a level barely enough to finance imports for 2 ½ months.

Short-term deposits amounted to a dangerously high level of 146.5 per cent of foreign exchange reserves by the end of March 1991. The rate of inflation soared exceeding 10 per cent in 1990. Expectations of an immediate devaluation of the rupee led to withdrawal of deposits by non-resident Indians. A spectre of default on short-term loans and downgrading of India credit rating loomed. Such was the nature of crisis that it compelled India to go in for structural reforms.

The other drawback of planning in the first four decades has been that industrialisation to which a large chunk of resources were allocated failed to generate adequate employment opportunities and the goal of transformation of occupational structure by transfer of population from agriculture to organised industries and services remain unfulfilled. The occupational structure remained almost unchanged, Besides, rate of unemployment increased as the increase in employment opportunities could not keep pace with the growth of labour force. No wonder that the change in plan strategy was called for.