Supply Side Economics and Supply Management in India!

Supply Side Economics and Management—Introduction:

Supply side economics (SSE) as a body of theoretical ideas, has far less substance or elegance than either the standard Keynesian income-expenditure model or the new classical economics.

Actually, supply side economics does not constitute a coherent set of relationships like the Keynesian model, relationships which explain how the macro economy works.

Supply side economics is based on two propositions—first, full faith in the validity of Say’s Law of Markets and secondly, a belief that tax rates are the prime determinant of incentives, which in turn, are the prime determinant of production. Basically, supply side economics is as much, if not more, ideological than it is economic.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Supply side economists insist on the validity of Say’s Law because it is in part an article of faith, a belief in the efficient working of the market system. It is also a logical necessity to explain for their basic argument, namely, that it is possible to explain how the economy works by approaching it from the viewpoint of aggregate supply rather than aggregate demand. Contemporary supply side economics deals with what Keynes called a real exchange economy—an economy which uses money, but only as a natural link between the transactions in things. It (SSE) does not allow money to enter into motives or decisions-—as it does in Keynesian theory.

Supply Side Economics—the Message:

When we talk of supply side economics, it only means manipulating the aggregate supply curve by modernisation, rationalization, skill formation, liberal depreciation, reorganization, cost manipulation (while these are treated as constant parameters during demand management). For an economy clearly in need of major revitalization the provisions of bringing depreciation charges more in line with the current cost of capital gains and high taxes as at present will shift the scarce capital resources both in the developed and developing economies from the higher to the lower productivity levels adversely affecting the supplies.

SSE shifts the emphasis from aggregate demand management of the economy to micro-motivations for productivity. The stress is transferred for distribution of income, monetary and fiscal policy and ‘fine-turning’ of the economy to incentives for the supply of labour, improvements in productivity and removal of restraints on optimizing activities.

The most common theme of SSE is the responsiveness of work, productivity, saving, investment and enterprise to after-tax rewards. High tax rates are opposed because they discourage economic activity; divert resources to tax-shelter industries and tax exempt goods; waste fine talents of lawyers, accountants and consultants in search of loopholes in tax laws; drives economic activity underground; induces tax evasion and encourages smuggling and fraud; and worst of all, causes the disintegration of the moral values of the nation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The proper characterization of supply side economics is a mystery to many. There are those that believe that the Supply-side theory is the one that holds that tax cuts pay for themselves. Others believe that this theory dictates that fiscal policy be only concerned with the supply-side of the economy. A third belief is that supply-side economics is whole-hog for government intervention to promote saving and investment through subsidizing these activities.

All of the above are false characterizations. In simple terms, supply-side economics is the application of price-theory to aggregate entities in the economy—nothing more, nothing less. It has as its underlying philosophy the belief that the market is stable and, if left to itself, will lead to an efficient allocation of resources.

The essential argument of SSE is that adding to supply unlike adding to demand, is not a zero- sum game. In order to make something a producer need not be given any money—instead he needs incentive—an intangible. Consumption, on the other hand, is really zero sum—in order to stimulate demand a policy-maker gives someone $50, then he must either take the money away from someone else, or suffer the central bank of the country to print it, thus marginally devaluing everyone else’s money.

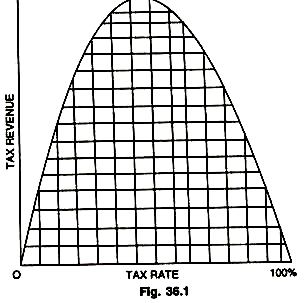

Supply and demand are far from being symmetrical though text-books suggest that these are exactly so. They differ in this crucial respect; things are consumed with cash—but made with effort. Supply-siders think of high tax rates as potential barriers to commerce—not as revenue collecting devices— tax rates are one thing; tax revenues are another. They argue that high tax rates collect tiny revenues; Laffer’s Curve graphically makes the point that a 100 per cent tax rate will collect no revenue as is illustrated in the Fig. 36.1.

According to economist Arthur Laffer, there is a close relationship between tax rates, revenues and productivity. When the tax rate is 100 per cent, all revenue ceases; people will not work for nothing. On the other hand, if the tax is zero, there is no government. Somewhere there is an optimum point on the curve where tax rates will produce the desired revenues—and the desired national product.

That point is variable, but basically in a democratic system, it is, to quote Dr. Laffer, “where the electorate desires to be taxed”. Too much of a tax burden can lower incentives to work. Revenues—and production—will fall. Lower taxes can increase both. There is nothing controversial about the curve itself, which diagrams one of the most basic propositions in economics. At the left hand side of the scale, the government imposes no taxes on income and so gets no revenues.

Moving right along the scale, as the tax rate increases, so do the revenues. But when the rates get high enough to discourage work and encourage tax avoidance, ever higher rates produce less revenues (the downside of the hill). If the tax rate reaches 100 per cent, it yields zero revenues—no one would bother to earn taxable income if the government confiscated all of it through high tax rates.

Keynesian analysis holds that the first effect of a tax change is to change the level of disposable income in the economy. The supply side view is that aggregate income, in real terms, cannot change at the outset but can only change when output increases. According to supply-side economists, the only effect, at the first level of a tax change is a change in the relative costs confronting economic factors in the economy. Acceptance of this fact leads to quite different approach to tax policy from that pursued in a Keynesian framework.

Supply-side economists hold that market is inherently stable and left to itself is the best and most efficient allocator of resources—the government may intervene in those rare circumstances in which market fails to properly represent value through the pricing mechanism. The neo-classical or supply-side analysis, in contrast with Keynesian approach treats changes in income as a second level consequence of a tax or tax change.

The first effect, they assert, is the change in one or more of the relative costs which private sector entities confront. They believe that every tax has the attribute of altering relative costs. As such, supply siders believe tax changes should–always be expressed in rates and the thresholds at which they apply; to do otherwise is to posit a static universe in which there is no post-tax-change shift in incentives.

Thus, Laffer Curve is a graphical representation of the disincentives created by high tax rates, is an essential element of a brand new theory called Supply-Side Economics. Its recent emergence signaling the beginnings of a return to micro or Classical from macro or Keynesian economics is, no doubt, the most important development in economic theory in the cast 25 years—especially during the last decade of glaring phenomenon of stagflation.

Features of Supply Side Economics:

An important feature of SSE is the issue of incentives and tax cuts. It constitutes the basis of radically different perspectives on economic activity of supply side and neo-Keynesian theory—supply side economics treats incentives as the main engine of growth—incentives energies the economic system— unlike Keynesians they do not take it for granted—these incentives are blunted and thwarted by a heavy tax burden.

All that the Laffer Curve says is that, after a certain point a tax—or the tax level as a whole can become counterproductive by adversely affecting the incentives. The central theme of economic growth is that people should work less hard—but more productively—and this is what the supply side theory tries to achieve. The supply side economists seek the removal of disincentives to saving and investment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Supply siders believe that a permanent cut in tax rates (as opposed to low income credits and piecemeal concessions) powerfully stimulates supply of all goods and services produced by the economy thereby stimulating the incentives to produce, save and invest. Tax cuts must be so shaped as to encourage production than to boost demand—especially when the problem is to fight ‘stagflation’.

Their main contention is people don’t work to pay taxes. People save to make an after tax rate of return on their savings—so these are the personal and productive incentives that matter in the disposition of income, of production and of savings—when you change incentives—you change human behaviour conducive to growth, production and saving.

It must be realized that the crucial source of creativity and initiative in any economic system is the individual investor. Economies do not grow of their own accord or by dint of government influence. They grow in response to the enterprise, initiative and dynamism of people, entrepreneurs who are willing to take risks encouraged by incentives. That is why, Schumpeter, in his model of growth gave a key role to skill formation, entrepreneurial behaviour, dynamism and innovation—these constitute the essential ingredients of growth in any society—believe the supply-side economists.

Supply-side economists believe that the problem of stagflation couldn’t be tackled because we have been taxing work, output and employment and subsidizing non-work, leisure and unemployment during the past decade or so. The real theoretical core of supply side economics rests in the belief that the major reason holding back production, causing unemployment creating inflation and leaving the government with insufficient revenues and larger deficits is taxation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

More specifically, supply-side economy maintains that marginal tax rates and the real source of economy’s problems. The marginal tax rate is the progressive increase in the tax rate applied to each increment of income as the tax-payer moves into a higher tax bracket every time his nominal money income increases.

Jude Wanniski, a great advocate of SSE says, “that the concept of marginality is crucial to understanding of economic behaviour very few people think of the margin, but everyone acts on the margin “Production comes about because people are willing to work, and people work for only one reason—to maximise their welfare. It is at this point that, taxes enter the picture, particularly the marginal tax rate. Taxes are a disincentive to production.

Taxes on capital discourage investment and taxes on people discourage work. This is the essential message of supply-side economics. It is in this connection that Professor Laffer developed the concept of ‘wedge’, especially a ‘tax wedge’. This is the gap that government through its power to tax and to regulate introduces between what an individual gets for working and what the individual is allowed to keep. “Marginal tax rates of all sorts stand as a wedge between what an employer pays his factors of production and what they ultimately receive in after-tax income–therefore, to increase total output taxes of all sorts must be reduced. These reductions will be most effective where they lower the marginal tax rates the most.”

The supply-side economics emphasizes the tax rate changes because tax rate changes affect relative prices, output and growth. Higher tax rates create preferences for leisure to work, consumption to saving and allocation of resource, to non-market activity to market activity.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Disincentives for work and saving affect supply of labour and capital, and all marketable goods and services and hence economic growth and price stability. Much to the charging of the proponents, its basic idea remains extremely simple… “If the rate of taxation is raised, the incentive to work, and consequently the national income, may fall.” According to this view, beyond a point, this decline is so sharp that the total tax collection (which depends on the national income) falls as well. The American “Supply-siders” argue that in the US and many other countries during the 1980s the existing tax rates have gone past this critical point. Hence, if the tax rates were cut, national income would rise and, more paradoxically, so would the total tax takings.

Role of Government:

The SSE economists view the government as essentially non-productive, if not positively wasteful. They think that the ultimate test of the legitimacy of production, so to speak, is the market. Productive activity is basically market determined activity. From the ‘wedge’ analysis it is easy to understand the hostility to SSE to government activity. Therefore, the SSE insists that government should do those minimum necessary acts which are essential to maintain a lawful and orderly society including protecting it from external aggression—all else is waste; The SSE is emphatic about the inefficiency of government regulations.

They do not deny the necessity of government but hold that its virtues are minimal. They consider government regulations as a necessary evil to be tolerated. Beyond that limit, SSE wants to roll back government, to get it off the backs of the people to prevent its wasteful use of productive resources.

Importance of Capitalism:

SSE’s “believe in capitalism, in the enriching mysteries of inequality, the inexhaustible mines of the division of labour, the multiplying miracles of market economics, the compounding gains from trade and property”. By focusing on the processes of production and innovation, they rely on an ‘unremitting cultivation of the supply of new goods’ through a renewal of faith in chance, providence, and Schumpeterian ‘creative destruction’ to capture the crucial sources of creativity and initiative for the promotion wealth, prosperity and concord.

The SSE’s are champions of capitalist order and individualism. Their main theme is that “Effort and enterprise must be unleashed from the shackles of governmental control and regulations and must be encouraged through incentives in the form of tax reductions in order to promote production”.

Emphasis on Growth:

Back of Adam Smith can be described as its chief motto, though not in the sense of returning to some purist version of laissez-faire. It may sound incredible, but supply side economists really do believe and preach that if you want economic education—The ‘Wealth of Nations’—is still the best book to read. They realize Smith’s ideas have still great relevance to the economic problems of developing and developed countries in the matter of industry and trade. As such, supply-side economics naturally gives emphasis on growth, not redistribution.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It aims at improving everyone’s economic conditions over time, but not necessarily in the same degree or in the same period of time. The aggregate demand created by economic activity, as seen from supply side is indifferent to the issue of equality. Its bias is consequently in favour of a free market for economic activity, because this provides the most powerful economic incentives for investment, innovation and growth. However, those for whom economic equality is at least as important as growth will always want to see the government, to restructure this aggregate demand and will be indifferent to the issue of economic incentives.

Reaganomics:

A variant of SSE as followed by President Reagan of USA in 1980-82 to fight unemployment and inflation (stagflation) is called ‘Reaganomics’ in USA. While the expression Reaganomics is not being heard of much lately, it is still the most popular phrase for referring to the overall economic policies followed by Reagan Administration and based on supply-side economics—that is, the transfer of resources from relatively poor people to the relatively rich ones—through cancelling or reducing various social services, transfer of resources from social needs or development assistance to the so called ‘military industrial complex’ etc.

Other important features of Reaganomics were de-regulation or reduction of government controls on industries, free trade, reduction of subsidies etc.—all essential elements of the thesis of supply-side economics as adopted in actual practice in USA. Strangely enough, the reduction in personal and corporate taxes made by Reagan Administration under the recovery programme of 1981 did not make any dent in the recession and bring any increase in production and growth. On the other hand, combined with monetary restraints, interest rates went high—deepening the recession and widening budgetary deficits resulting in indifferent health to dollar at times.

Keynes and Supply Side Economics:

It would be equally important to understand that the supply-side economics, though identified most readily with a current school of thinking, has its roots in the classical economics, particularly the work of J.B. Say. It is said that Keynes refuted Say’s Law but what is not realized is that he rehabilitated it through a different route (Y = C + I), through the income-expenditure model.

The very fact that there cannot be any stable equilibrium in the economy unless the sum of expenditures on consumption and investment demand is high enough as to be equal to income generated (supply) establishes the validity of Say’s Law even in modern conditions. Y = C + 1 is nothing but an application of Say’s Law in the long run when lags have worked themselves out in the economy. Across the entire system, the purchasing power and producing power must always balance though with a time lag.

It is in this sense that we speak of Say’s Law as still valid. As such, the actual works of Keynes, even in relation to Say’s Law and the role of supply, are far more favourable to supply-side economics than current Keynesians realize.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the Keynesian mode, investment rules the roost—which depends upon effective demand and marginal efficiency of capital—both in turn, depend on anticipated profits on “the proceeds that the entrepreneurs expect to receive”. These two concepts affirm Say’s Law and assert the supremacy of supply. Keynes restored to the centre of economic activity the vital role of individual entrepreneur. It is free men rather than abstract forces or mechanisms that impel the Keynesian economy.

In his view, the key to material progress lies not in the working of automatic accumulation or in passive thrift and savings or in a benign tendency towards general equilibrium but in ‘skilled investment’ designed “to defeat the dark forces of time and ignorance which envelop our future”. Because the Keynesian world is not rational and predictable, the true message of Keynes cannot be reduced to mathematics or a scheme of reliable planning. Reversion to supply side means leaving the luxury of rigorous models and computations and again entering the fray of analysis and examination history and psychology, business and technology. Economists must again focus on the multifarious mysteries of human social behaviour creativity which Adam Smith elegantly addressed in ‘The Wealth of Nations’.

Keynes and Laffer:

The supply siders emphasise that the real benefit of the tax cuts would be to give greater encouragement to purchasers and investors, who can take factor risks and invest with confidence to increase the supply of goods and services. Keynes was very conscious of the role of the entrepreneur. He had argued that it is not just through the cold calculations that the best investment decisions are made. It is the readiness to take risks, apart from profits which enables them to set up new enterprises to take economy forward. Upto this point one may say that despite differences in emphasis, there is much in common between Laffer and Keynes.

The real difference between them is that while Keynes argued that insufficiency of demand could discourage production. Laffer maintains that it is the lack of incentives which comes in the way of higher production. When we speak of effective demand, we mean the demand which has the backing of purchasing power and can be manifested in the market in the purchase of goods and services. Ineffective demand does not count. On the other hand, we should recognize that there may be purchasing power but it remains ineffective, because the real demand is not there, on account of insufficiency of goods and services as the supplies are not in alignment with consumer demand. While Laffer was concerned with ineffective demand in the later sense, Keynes was concerned with it in the former sense.

Critical Evaluation:

Supply-side economics may be reviewed as a kind of humanistic rebellion; against the mathematical- mechanical type of economic analysis in which economic aggregates, themselves dubious in nature, are related to one another so as to achieve a supposedly accurate series of snapshots of the economic universe we inhabit. Supply-side economics is not interested in a manipulated or architected equilibrium because this is a wrong way to understand an economy that consists of the purposive yet inconstant behvaiour of millions of individuals profoundly influenced by all sorts of social, cultural and contingent factors—religious heritage, family relations, and not least, the actions of the government. However, it may be noted that supply-side economics is far from being new or revolutionary.

The SSE is not a unified body of thought. It is more concerned with certain recommendations of policy—tax cuts on earned income, tax incentives to increase savings, tax incentives to invest and growth a productivity etc.—an economic policy which must focus on the supply side of the economy— on the long-term capacity to produce rather than stimulating aggregate demand which only feeds inflation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The top exponents of this school of thinking—John Rutledge, Arthur Laffer, Irving Kristol, Paul Roberts, did not show much agreement except on the broad view that supply management is what is required to fight inflationary recession. About the relative efficacy of the different supply augmenting policies they differed. No one gave any exact definition of the so called SSE; only Arthur Laffer had a definite view, “Supply-side economics is nothing more than classical economics in modern dress”.

It is the same old wine in new bottles. The broadest generalization that can be derived from SSE analysis is that the net effect on government revenues, when account is taken of the changes in economic activity the tax cuts generates, will differ from that which is estimated when these economic effects are ignored. But this generalization is not unique to the supply-side analysis, hence is not its distinguishing feature.

Its main limitations are:

More Ideology—Less Analysis:

It is said that in the SSE approach ideology plays a more important part than ‘analysis’. The foundations of SSE lie in a particular philosophy, not in a particular analytical or technical framework. It is essentially a conservative philosophy.

The ideology is not progressive. Tobin rightly remarks “that without a Keynes or Friedman or Lucas, SSE lacks a sacred text; expanding its theoretical foundations. It is more spirit, attitude, and ideology than coherent doctrine and it has enthusiasts is of many minds”.

The intellectual roots of SSE are weak. What is really important for the topic of our analysis is that the classical world as depicted by the classical political economy was qualitatively—different from the capitalist industrial economics of today. Nevertheless, it is maintained by some economists that neo-Keynesian macro dynamic paradigm can very well take care of SSE oriented policy recommendations as well. This neo-Keynesian model can also well serve the theoretical foundation of supply-side economics.

No Solution of Poverty and Unemployment:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The SSE based model which depends upon skewed distribution of incomes, can hardly tackle the problem of poverty and unemployment. The demand generated by unequal distribution of incomes cannot sustain supply-based model and when the internal demand cannot absorb the supplies, the economy looks to exports which cannot provide an escape route. The critics argue that the model based on SSE is a capitalist model imposed by big business, international private capital, multinationals, IMF and the World Bank.

SSE suits the interests of dominant classes and generate more exploitation instead of tacking the problem of poverty and unemployment. According to Keynes that there are weighty considerations to reject the thesis of SSE. Survival of the fittest and the elimination of the rest, however valuable as a means to promote production and efficiency, will have to reckon with the uplift of the unfortunate. This important fact must be included in the context of character of the competitive struggle, especially in the context of underdevelopment.

The SSE hypothesis is in conformity with the needs and wishes of the business world of the day; though the vitality of its conclusions has outlived, the age in which it was born. It is an orthodoxy, ruling over the people by hereditary right than by inherent merit of its validity. Private enterprises system, no doubt, is a marvelous one.

But ‘there is a great deal it cannot do, and much that it does badly..’ Unlimited free enterprise, limited government and total neglect of, or even opposition to, redistribution of income, are part of an economic dogma, much of it provided by famous economists of the past as a guide to policy in a world different from our own.

Tax Cuts not Dependable:

Even on specific SSE proposals, there are many imponderables. Tax changes have both income and substitution effects. The SSEs assume that the substitution effects will dominate over income effects. But there is absolutely no ground for such an assumption. In the same way, what is the guarantee that in India or in any other country the tax revenues are beyond the peak level as depicted in the Laffer curve? Is there any a priority method to determine the optimum tax rate and that too from a given GNP?

Household saving may be greater by some fraction of the tax cut; but government dissaving will be greater by the full amount. How can anyone be sure that a tax cut will increase savings? “The effect of a tax cut on savings, investment, output, tax revenues, will very likely vary between countries and over time within a given country for various reasons including cultural factors, level of current tax rates, expectations regarding inflation, and the investment climate. Relationship among economic variables as well as people’s relations to economic, political and social developments change over time in unpredictable ways. In short, there are no constants in human behaviour”.

No Trickle down Effects and Rise in Income Inequalities:

“The only sure results of supply side policies’, asserts Tobin, “are redistributions of income, wealth, and power—from government to private enterprises, from workers to capitalists, from poor to rich”. SSEs are not averse to this result. They affirm that such a redistribution will, in the long run, benefit the immediate losers as well as the beneficiaries. This is the famous ‘trickle down’ theory. Will a larger cake assure a bigger slice for everybody, as the SSEs claim or assure?

After a careful evaluation, this is what Jameson says. “………… All the studies agree that the policies adopted were successful in attaining the results desired: GNP grew, and at rates which were far higher than the historical experience ……… No matter how the data are organized, post-war growth in output was impressive. Even with the OPEC countries excluded, from 1960 to 1974, GNP in the third world grew faster than in the advanced capitalistic countries, though somewhat more slowly on a per capita basis

The increase in supply under the types of policies………. came only at the expense of the poor and the powerless, and income was redistributed in favour of the rich. The costs now seem too high, the type of ‘development’ which occurred was too skewed, the loss to the poor, by their being left behind or having their plight deteriorated was also too great. There was no trickledown effect as claimed by SSE.

Hans Singer, himself once an advocate of the ‘trickle down’ model of economic growth, now writes, “with the benefit of hindsight it is not too difficult for us to see what is wrong with this doctrine” (SINGER—1979). He cites three main fallacies in this argument. First, automatic ‘trickle down’ is most unlikely because there is unequal access to the opportunities of producing or obtaining the income from incremental GNP. Richer groups have privileged access, and so the larger slice goes to them, creating sharper inequalities.

Second, it is not necessarily true that inequality of income distribution is needed to promote saving and productive investments. Neither side of the equation is necessarily true. In LDCs, poor people do save and invest productively. Much of the investments in economics with unequal income distribution are by foreign investors and multinationals, and the profits and surplus are drained away from the developing country. Third, once the economic structure has been geared to unequal income distribution and the domestic market aligned to it, it becomes difficult both economically and politically, to change it back at a later date in favour of greater equality and a social welfare state.

Weak as a Theory of Underdevelopment:

From the angle of underdevelopment, the most objectionable parts of the SSE arguments are:

(i) Neutral role for government;

(ii) Small size for the public sector; and

(iii) Support for the maintenance of the existing inequalities.

In their view, the economic game shall be played by private individuals and the state must act as a neutral referee, blowing the whistle whenever the rules are violated. If the players are provided with the right incentives, then the game will be vigorously and efficiently played. It is imperative that the referee shall not interfere in the game. This line of reasoning is manifestly wrong. The SSE’s chose to ignore that the state is not a neutral referee in the first instance.

They fail to note that the strong arm of the state is used to sustain, as well as to restrain, the strongest in the game. They are oblivious to the fact that the players are not equally matched, both among the nations, and within the nations; and that any game among un-equals will result in the extermination of the weak.

Less Role for the Public Sector:

The objection to a major role for the public sector is not also well-founded in the context of underdevelopment. Where motivations are blunted by the aggregate economic environment, mere removal of restrictions without active encouragement and participation by the state will only result in the smaller fry being swallowed by the bigger shark. Where private sector is unwilling to, or is incapable of, fulfilling the development needs of the nation, as in the case of the provision of social overhead capital, there is no other alternative than enlarging the public sector to achieve that goal. However, this kind of reasoning does not meet the approval of SSE.

Economic Development and Supply Side Economics:

Just as their famous adversary, J.M. Keynes, addressed the policy prescriptions in his ‘General Theory’ to the developed world in the depth of a deep depression, the SSE’s also direct their policy prescriptions to remedy the malady of ‘stagflation’ in the developed world after 1970s. There is thus, very little in the policy prescriptions of the SSE’s which is pointedly aimed at solutions of underdevelopment. It is well recognized that underdevelopment is due both to insufficient aggregate supply and inadequate aggregate demand. So post-war theories of development have put the spotlight on both sides.

It is equally well known that demand management is more a short-run phenomenon— so there is no wonder that most of the development theories which attack the problem from the angle of long-run are supply-oriented.

The theories which recommend utilization of surplus labour potential of the UDCs, such as Nurkse’s Balanced Growth and Lewis’ Unlimited Supply of Labour models, are no doubt supply-oriented. So are the Stages of Growth models, with their main emphasis on the increase in the rate of savings. Theories which advocate extension of markets to enjoy the benefits of division of labour, both of the balanced and unbalanced growth varieties, aim at increasing aggregate supply. Theodore Schultz, with his stress on human capital development and optimization techniques, is again a supply-side theorist.

Harvey Leibenstein’s theory insofar as it is used to explain productivity differences between countries as differences that arise from difference in motivation, management, drive and spirit, is undoubtedly nearer SSE position. All major theories which concentrate on factors affecting efficiency, entrepreneurship, human resources development, increase in productivity, innovations and technical change, are to be grouped with the theories which aim at increasing supply.

Theories which suggest that the route to development lies via unrestricted international trade again are based on increasing supply. In that restricted sense, almost all theories of development are supply- oriented theories. The general argument that the cake must first be enlarged before it is distributed and that the benefits will ‘trickle down’ from the higher income to the lower income groups as is seen from the historical experience of developed countries, can be cited to support the SSE view that increase in inequalities is a motivating force for economic development.

Thus, the statement that a survey of the writings on economic development in the post-war period shows clearly that the dominant concern has been the supply-side economics is only partially true. As pointed out earlier, most of them were supply-oriented; but they do not embrace all the SSE proposals, especially reduction of the role of government and reduction of taxation. Under the influence of the SSE movement in USA, the World Bank and IMF are giving more active encouragement to private sector financing than before.

Private entrepreneurs face risks, whereas public sector managers are risk averters; private enterprises have to compete to survive, whereas public enterprises are protected from failure by government interventions; where efficiency in production becomes confused with equity in distribution, neither goal is well served. But a total conversion to SSE policies is nowhere to be found among the writings of leading development economists.

In its totality, the SSE policies are incapable of promoting development of the UDCs. But particular aspects of SSE arguments are very relevant. According to Keith Mardson, “Pervasive poverty is created by oppressive taxation; central planning benefits the elites rather than the entrepreneurs; soft currencies rob the masses of the ability to save ; initiative is inadequately rewarded ; domestic industry supplying non-essentials (such as stereos, videos and refrigerators as in India) are over- protected; consumer choice is unnecessarily restricted ; planning mistakes frequently occur; political power is severely abused”.

But the SSEs claim that its potency has increased with age. It is, however, certainly wrong medicine to cure the malady of ‘underdevelopment’. SSE is neither revelation, nor revolution. It is only a renewal, a reaffirmation of classical propositions, valid in a limited sense. The world has changed, completely since the classicals wrote. The supply siders are unwilling to face the changed reality.

Supply Side Economics and Developing Economies:

The Supply Side economics has great appeal in developing economies because the chief problem in these economies is that of increasing the supply of goods and services—i.e., of increasing the supplies to cope with the pent up desires.

The problem is two-fold:

(i) To convert pent up desires into effective demand by providing additional employment (real incomes) and not money incomes,

(ii) To generate surplus, especially of food and to increase the supply of goods and services to cope with this so that inflationary spiral is avoided.

For this, we may follow one sector model giving importance to agricultural sector or two-sector model giving importance to agriculture and industry. However, balanced growth in agriculture and industry of rural and urban income, output and employment sectors would be in order, and the question of choosing between the leading sectors may be postponed at least in the initial stages of development. The underdeveloped countries converted pent up desires into effective demand by the creation of money but failed to bring them into right adjustment with the supplies.

Effective supply is that level of output in the economy at which the demand of the community is satisfied. An excess of which causes depression and a deficiency of which causes inflation. In underdeveloped economies both the aspects are studied as aspects of effective supply; just as in advanced economies we study them as aspects of effective demand. A general theory for underdeveloped countries, according to supply-side economists, would be a theory of effective supply and not of demand management at least in the initial stages of economic development.

In advanced economies an increase in the supply of money, other conditions remaining the same, would lead to a decline in the rate of interest; hence, investment and employment will rise. In underdeveloped countries, on the other hand, an increase in the supply of money will result in inflation and not in an increase of employment. This is because a depressed but mature economy has not only idle manpower but also excess capacity and raw materials; while in underdeveloped countries the complementary resources like capital stock are lacking.

Thus, it is said, the theory of demand management as enunciated by Keynes, does not hold good in underdeveloped countries. Here the problem is more of increasing supplies and raising the surplus than of generating demand. The reason why in underdeveloped countries a high level of real incomes and full employment cannot be attained, in spite of the favourable consumption (C), investment (I) and liquidity (L) functions is that determine only the volume of effective demand at a level at which goods cannot be produced except in conjunction with a commensurately great magnitude of productive capacity—which is lacking in developing economies.

Although, G and I functions are more elastic with reference to several variables yet their position is lower than in the developed systems. For structural and ‘infrastructural’ reasons output cannot be readily responsive to increases in demand. The increase in demand as such may eradicate cyclical unemployment in advanced economies but it may be quite ineffective in eradicating chronic unemployment and underemployment in underdeveloped countries.

Manipulation of demand through monetary expansion may prove more harmful as this cannot be an effective substitute for programmes to improve labour productivity and mobility, skill and management, creative enterprise and efficient bottlenecks. As a result of low supply elasticities and its natural corollary of price increase, large increases in the volume of imports take place if money income is expanded by an increase in aggregate expenditures or the expansion of money supply through the banking system. It is, therefore, clear that an expansion of demand and therefore development problems are to be attacked from the supply side only in such economies by giving all kinds of incentives, assert the supply-side economists.

A survey of the writing on economic development in the post-war period shows clearly that the dominant concern has been the supply side discovering how can economy’s output be increased most effectively. Sir Arthur Lewis got his Nobel Prize in 1979 for his contributions to the analysis of the process by which the transfer of surplus labour into more productive employment would increase output of the economy.

Subsequent work kept up the pace by examining various factors affecting this transfer and its effect on supply. Theodore Schultz got his share of Nobel Prize partly for criticism of the idea of labour surplus but more so for his contribution to an understanding of the conditions of supply in the agricultural sector, with emphasis on factors affecting efficiency and technical change to productivity.

Other sources of increased supply also got due attention in development literature— like human resource development through education and health, entrepreneurship and infrastructural ingredients to allow for more efficient production and allocation of resources. In all models—saving was given a central role being the chief source of investment funds for increases in productivity and growth. Problems of foreign aid and foreign investment were discussed and policies formulated with the same background and context.

In a 1963 essay, Mahbub-ul-Haq, the chief economist of the National Planning Commission of Pakistan and a supply-side economist made out that, “the best form of social security is a rapid expansion of productive employment opportunities to all through the creation of sufficient capital by some. There exists, therefore, a functional justification for inequality of income if this raises production for all and not consumption for a few. The road to eventual equalities may inevitably be through initial inequalities.”

He dismissed any policy emphasis on distribution and welfare state considerations. Growth in supply was the goal; increases in saving were fundamental to the process of growth. He pointed to a linkage between saving and income distribution which has been the chief cause of the resulting development debate. He argued that economic policy should favour entrepreneurs and those with high marginal propensity to save—that is the wealthy—for this would increase saving, investment and growth.

Attempts have been made to survey post-war developments in the ‘Third World Countries’ which followed supply-side approach. They range from the studies for the World Bank by David Morawetz to those of Bill Warren and John Gurley done from a Marxist perspective. A comparison with Marxian socialist countries favours the Third World. Specific Third World countries which grew very fast during the period are: Korea, Singapore, Brazil and Taiwan.

All the studies are unanimous that the supply side policies adopted were successful in attaining the desired results: GNP grew and at rates which were far higher than the historical experiences—GNP per capita also grew in most cases. All this is a positive proof of the effectiveness of supply-side economics necessitating and justifying its continuation in developing economies.

However, a broader and a long range view of development would imply that increases in supply should be taken as a means to an end—the end being growth with ‘equity and social justice’. With the dawn of 1970s and through the decade some dissatisfaction with the supply-side economics originated. It was based on analysis, experience and facts that came to light after detailed empirical studies in income distribution.

It was realized that the translation of growth rates into the above ends was not direct; that high growth rates did not of necessity and by themselves enhance performance in the more crucial sectors or central areas of the economies. This led Mahbub-ul-Haq to revise his opinion. He wrote again in 1971: “It is time to stand economic theory on its head, since a rising growth rate is no guarantee against worsening poverty……….. Divorce between production and distribution policies is false and dangerous. The distribution policies must be built into the very pattern and organization of production”.

Despite rapid growth rates in the Third World, the income distribution in a large percentage of countries became more skewed toward the wealth—and this inequality showed no tendency to reverse itself and to that extent supply-side economics has been found wanting. Moreover, there is no evidence to show the close link, if any, between inequality and growth—the awareness dawned that the costs of development entailed in these policies are too high.

Spurs to investment no doubt aided growth but worsened income distribution making rich richer and poor poorer. This strategy of growth which had relied on the savings of the wealthy as the main engine of growth became unacceptable—the emphasis had to be on dealing with poverty and shifting the distribution in favour of the poor—that is, growth with equity.

It may, however, be noted that this simple reaction to supply side economic policies and their implications for income distribution doesn’t imply an option for stagnation, nor does it mean its abandonment, nor the revival or super imposition of demand management. All that it means is the imperative need for reorientation and modification in supply side approach to avoid its adverse implications on income distribution.

There are certain countries like Taiwan, Costa Rica, Singapore which have been able to attain high growth rates without the detrimental aspects of mal-distribution of income. There is already a major reorientation in the approach which has isolated a number of factors—such as wide-spread assess to productive resources, broad based human resource development as essential elements in a growth with equity strategy, while maintaining emphasis on supply.

The development efforts in countries like India, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Burma, Sri Lanka and others have been based on wrong strategies of demand management under the influence of Keynes. Keynesians and Western economic model of growth—which resulted in the present formidable inflation and stagflation. These economies could as well follow the supply-side approach in their development efforts without being unduly scared of the negative redistributive effects of income.

Moreover, such a strategy is not against the basic philosophy and economic policy of mixed economy being followed in these countries with a respectable role for the private enterprise and free market. All that is required is to allow the free operation of these forces by removing unnecessary restrictions on economic activities by suitable amendments to rules and regulations affecting production and by encouraging incentives to produce by accelerated depreciation, investment tax credits, rationalization, skill formation and reducing high tax rates resulting in parallel economy, black market, tax evasion etc.,—assert the supply side economists.

India and Supply-Side Economics:

In India, tax evasion, high rates of interest etc. clearly show that there is good deal of scope to go back to Smith and allow the working of supply-side economics. When we say that the western or Keynesian models have failed us in developing economies what we mean is the adoption and trial of supply-side economics in those economies. It is within the scope of their political set up, institutions and philosophy.

They emphasize the small farmer with individual proprietorship on land and small- scale industry with intermediate technology—under these circumstances, supply-side economics suits very well for it glorifies incentives, hard work, production and savings—the very essence of growth in developing economies.

It would be better that in countries like India we do not pose or impose an artificial choice between the Keynesian approach and supply-side economics, so far as our own policies are concerned. The salient facts to remember are that in a poor country, low purchasing power is a problem caused by insufficiency of effective demand. Secondly, if more money is pumped into the economy, the level of consumption would rise more sharply without a commensurate increase in investment levels and supply of goods and services.

So, we may need to follow policies which may mean keeping some curbs on consumption and giving a special stimulus to investment and supplies. Such selectivity cannot be exercised greatly through macroeconomic measures which entail interventions in the economy which are neither Keynesian nor the supply-side based. Needless to say that such intervention, if necessary, has to be made very carefully if these are not to prove counter-productive.

Thus, in the classical framework of the Indian economy in which money functions more as medium of exchange than as form of value—an expansionary monetary policy exhausts itself in inflationary price rise rather than in reduction of interest rates to enhance deficit financed by resort to the printing press rather than by taxation and market borrowing is expected to shift the Keynesian aggregate demand curve to the right; but as the economy operates largely in the classical range rather than in the Keynesian range in the IS-LM model the rightward shift in the IS curve results largely in inflation. The real problem of the Indian economy lies in shortages and in in-elasticities of the factor endowments—in paucity of marketable goods and services and in the constraints for augmenting aggregate supply.

In view of the classical character of the Indian economy an aggregate supply-side approach which emphasizes production and growth as function of capital and labour is essential. Growth should be attained through repeated reinvestments of economic surplus at every stage of development in the form of profit incentive to enhance capital productivity and wage fund—labour productivity.

The share of profit to wage, of capital to labour, in economic surplus should be determined with reference to availability of factor endowments and long-run viability of the economy. The question whether this supply-side growth should be attained in a perfectly competitive free enterprise economy or within the present framework of mixed economy with a dominant public sector is a matter of value judgement.

In developing economies when administrative prices are raised on the plea of adjustment of prices to costs—fair return on capital and incentives for producers—the situation on the price front is bound to be fully stretched. This is what seems to be happening in India. SSE has in fact played havoc during the 1980s and the efforts to control inflation have itself been distorted. It has turned into a drive to depress the incomes of all sections of the people instead of curbing the profits of capital and the profiteering of producers and traders.

It has resulted in the scaling down of public investment in social welfare concessions for private enterprise, both in the industrial and agricultural sectors. Even the monetary and credit policies have been geared to serve similar purposes. The net result of all this has been an increase in income disparities and to bring about a further shrinking of the purchasing pow6r of the masses—while production for profit has led to a boost in investment in those areas catering to the elitist demand. The development as well as utilisation of infrastructural facilities, inadequate as they are in developing economies becomes further lopesided.

The basic problem of growth of underdeveloped and developing economies in countries like India is ‘structural’ problem and structural factors should be given primary importance. In order to reduce the evils of mixed economy in economies like India, what is needed is a ‘mixed baggage’ of policy instruments—monetary, fiscal, physical and direct measures under the active supervision and direction of government. The Indian economy which has now (in recent years) been further liberalised and emphasis has shifted to export promotion, import liberalisation and market economy, reduction of poverty becomes a more difficult task.

Many developing economies which have adopted SSE based growth models have three main features:

(i) External market which is necessary to create demand for supplies to make up the deficiency of demand;

(ii) Foreign capital which provide resources as well as technology;

(iii) Dominant class of industrial capitalists whose consumption standards form the base of home market and in whose interests the state power is primarily interested.

When supply-side model is rejected we do not advocate the demand supply approach of the type of Paul Samuelson, Keynes, Friedman, Joan Robinson or James Tobin, etc. These models are also models of more or less free market economies which ignore the distributional aspects. The models of development and removal of poverty in growing economies like India are taken into consideration— are the ones which constitute a synthesis of supply and demand with a view to regulating production in accordance with the needs of consumption and investment and welfare of the masses.

Conclusion—A Sham Dispute:

However, it must be understood that the dispute between the supply-side economics and demand side economies is a sham dispute and there is no need to assume extreme positions nor a choice between the two be forced. There is certainly a difference in perspective; supply-side economists look at the economy from ground level, as it were, that is, from the point of view of the entrepreneurs and investors who are identified as the prime movers.

Keynesians look at the economy from the standpoint of a government which intervenes discretely to preserve a harmonious economic universe. But it is wrong to infer that we live in a world in which supply and demand are continually at odds, so that we always are having to declare allegiance to one as against the other. They are, rather opposite sides of the same coin, coexisting of necessity, and there can be no question of choosing between them. The difference, if any, is one of degree of emphasis rather than kind depending on the state and nature of circumstances in an economy—whether inflationary, deflationary or stagflationary.

The analogy of Dr. Marshall of the two blades of a pair of scissors hold true here also—the upper blade—demand management is active and resorted to in deflationary situations and the lower blade—supply management—is activated to cope with a inflationary or stagflationary situation by providing incentives through tax cuts, investment credits, accelerated depreciation, skill formation, rationalisation, etc.

As such, in view of the interchangeability of the two approaches to the treatment of a particular situation prevailing in the economy, it is a matter of complete indifference and personal choice which one of the two approaches is used on a particular occasion. It would probably be true to say that supply-side economics did not forge nearly as new a theory as is being made out except the emphasis on supply which the present situation justifies in most of the economies.

It must be stressed that supply-side theory is not a new theory but one that incorporates teachings of the classical economists from Adam Smith to Alfred Marshall to Milton Friedman and to Norman Ture. It has as its philosophical underpinnings the belief that the market is inherently stable and that the free market is the best mechanism by which to assure the efficient allocation of resources. On an analytical level, the single most identifying characteristic of supply-side theory is the identification of first-order price effects and the rejection of first-order income effects as the initial effects of a given tax change.

Income effects are identified as second-order in analytical sequence and only occur in response to changes in the offering of capital or labour services due to changes in relative prices. The supply-side view holds that questions of inflation involve the growth rates of two factors in society— the stock of money and output (i.e., goods and services).

It may be understood that supply-side economics and its insistence that Keynesian demand management policies should be discouraged in favour of supply management and incentives are based on a total misunderstanding of the Neo-Keynesian theory of macroeconomic policies. They have never argued that supply side incentives are irrelevant to control inflation or stagflation.

What they insist on is an integrated policy where both demand and supply aspects of management must work together. Hence, the view that SSE as yet is basically a slogan and ideology without any acceptable economic theory to support its policy presumption. Supply-side management is no doubt required to cope with the current economic situation in advanced industrial countries of today and for this according to experts the neo-Keynesian macro-dynamic theory is adequate enough.