New Economic Reforms in Indian Economy!

It is evident from the reforms introduced in the Indian economy that from a planned economy it has moved towards a free-market economy.

Though we still have mixed economy with both the public and private sectors coexisting but the role of private sector which is governed by market forces has been greatly increased and that of the public sector greatly diluted. So we now have a mixed economy with greater orientation towards a free market and private sector.

More than a decade and a half has passed when we initiated economic reforms in 1991 laying greater emphasis on liberalisation and privatisation. Now, the pertinent question is whether these economic reforms have ensured higher and sustained economic growth which the supporters of these reforms argued that they would, whether these reforms have led to a higher growth rate and to the greater reduction of poverty and unemployment which was expected of them.

Rise in Foreign Exchange Reserves and Growth in Exports:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It may be said in favour of economic reforms that today we face no longer any foreign exchange crisis which prompted the initiation of these reforms. Foreign exchange resources which had gone too low in 1991 have substantially increased in the post-reforms period. Foreign exchange resources rose to 100 billion US dollars in Dec. 2003 and further to about 145 billion US dollars in March 2006 and on end-March, 2008, the foreign exchange reserves stood at 310 billion US dollars.

During 2008-09 there was capital outflow from India due to global financial crisis and as a result foreign exchange reserves fell to US $ 252 billion in March-end 2009. However, during 2009-10 there was reversal of capital flows and as a result foreign exchange reserves rose to US $ 270 billion on end-March 2010 and to US $ 300 billion in end-March 2011. Foreign exchange reserves were $ 275 billion in September, 2013.

New economic reforms, especially trade liberalisation, removal of excessive control over private sector and devaluation of rupee in July 1991 (and later floating of rupee) had a beneficial effect on growth of Indian exports.

The growth rate of merchandise exports picked up during 1991-97 when on an average growth rate of 11, 7 per cent per annum was registered. However, during the Ninth Plan period (1997-2002) rate of growth of exports fell to 6 per cent per annum due to global recession during this period.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

After 2002, growth rate of exports substantially increased and during 2003-04 to 2007-08 growth rate of 25.4 per cent per annum in exports was achieved. Thus reforms in the external sector have yielded good results in growth of exports and invisibles (i.e., services and private transfers). However, growth of imports also increased due to liberalisation of trade through reduction of tariffs and elimination of quota restrictions.

Even with the growth of imports balance of payments on current account improved; deficit in current account which was 3.1% of GDP in 1990-91 fell to 1.4% in 1997-98 and to 0.5 in 2000-01. For these years (2001-02, 2002-03 and 2003-04, there was surplus in balance of payments, that is, there was net investment abroad by the Indians. With 2004-05 onwards there has been again deficit on current balance of payments which was 1.2%, 1.1% and 1.5% of GDP in 2005-06, 2006-07 and 2007-08 respectively which was quite small. This represents net inflow of capital and is a good thing.

Control over Inflation:

The annual rate of inflation as measured by the change in wholesale price index (WPI) which was brought down from about 17 per cent in August 1991 to 4.5 per cent in 1997-98, again went up to year-on-year basis to 7.1 per cent in 2000-01. But it came down to 3.6 per cent in 2001-02, 3.4 per cent in 2002-03 and went up to 5.5 per cent in 2003-04 and 6.5 per cent in 2004-05. Average annual inflation rate (based on WPI, 1993-94 = (100) was estimated at 4.4 per cent in 2005-06 and around 5.4 percent in 2006-07.

Thus, inflation was brought under control. It may however be noted that for controlling inflation, credit must be given to prudent monetary policy produced by the Reserve Bank of India. Even after economic reforms with exception of few years fiscal deficit has been quite large which generated inflationary pressures in the Indian economy. Tight monetary policy of the RBI succeeded in neutralizing to a great extent the possible inflationary impact of the large fiscal deficit.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, inflationary pressures were built up during 2006-07 and 2007-08 though with the adoption of proper monetary measures by RBI and reduction in fiscal deficit by the Government, they were kept under check. But from march 2008, inflation rate as measured by WPI flared up and year-on-year inflation rate crossed 9 per cent in June 2008 and continued unabated and crossed 11 per cent in August 2008 and reached a peak level of 12.6 per cent in mid-Sept. 2008.

As a result of supply-side measures adopted by the government and tight monetary policy adopted by RBI, inflation rate on year-on-year basis came down to 11.4 per cent in October and to 8.5 per cent in end-November 2008.

However, from the second half of2009-10 inflation rate again started rising and became a matter of concern. The financial year 2010-11 started with a double digit headline inflation of 11.0 per cent in April 2010. After remaining in double digits from April to July 2010, inflation started falling for the whole financial year 2010-11, WPI inflation was measured at around 9 per cent which was quite a high level. In spite of good monsoon in 2010-11 and high agricultural growth rate of 6.6 per cent in this year, food inflation jumped to double-digit level and stood at 13.6 per cent in Dec. 2010.

During FY 2011-12 also both WPI inflation and food inflation continued at an elevated levels and was around 7.3 per cent. However, inflation as measured by consumer price index (CPI) remained at a high level of 9.8% per cent Y-O-Y basis in March 2013. Food inflation rose to 18 per cent Y-O-Y basis in August 2013 despite 70 million tonnes of stocks of food-grains with government. Nearly double digit inflation rates in terms of consumer price index (CPI) and a very high rate of food inflation is a matter of serious concern as it erodes the real income of the common man. It hits the poor man badly.

However, it is important to note that current inflation rate is not due to economic reforms undertaken since 1991. It is the result of both supply-side and demand-side pressures presently operating in the Indian economy and both domestic and external factors are responsible for it.

Acceleration of Economic Growth:

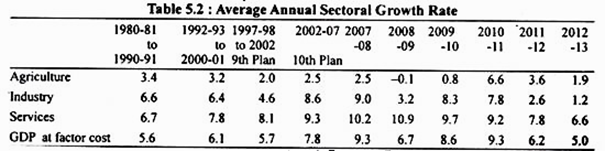

Though economic reforms have not ensured sustained economic growth during the over two decades since 1991, the overall picture that emerges is that rate of growth of GDP has gone up. We present in Table 5.2 below the overall growth of GDP and of various sectors in the Indian economy.

It may be noted that growth rate of industry where major reforms were undertaken, was estimated to be higher at 7.6 per cent per annum in the five year period during 1992-93 – 1996-97 (omitting the year 1991-92) as compared to 6.6 per cent achieved in the pre-reform decade 1980-81 -1990-91. The growth rate of 6.7 per cent per annum in GDP achieved during the period 1992- 93 to 1996-97 was also higher as compared to the eighties.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, during the Ninth Plan period (1997-2002), the growth rate of industry declined to 4.6 which is far less than the industrial growth in the pre-reform period. The overall growth rate in GDP during the five year period of Ninth Plan, 1997-98- 2001-02 was 5.5 per cent which was also less than that of pre-reform period.

The lower industrial growth during 1997 to 2002 resulted from global recession and also sluggish domestic demand conditions which arose due to decline in public sector investment and lower growth rate of agriculture.

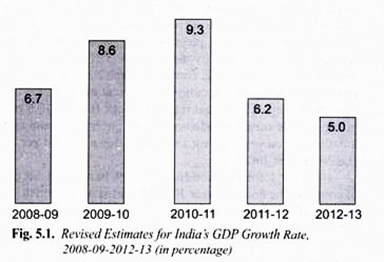

However, during the Tenth Plan period (2002-07) annual growth rate of industry rose to 8.6 per cent and of GDP to 7.8 per cent. In the four year period 2003- 04 to 2007-08, average annual growth rate of GDP has been over 9 per cent. Due to global financial crisis, growth rate in 2008-09 fell to 6.7% but it again went up to 8.6 per cent in 2009-10 and 9.3 per cent in 2010-11.

In fact, in the four years (2005-06, 2006-07, 2007-08 and 2010-11) annual average growth rate in GDP exceeded 9 per cent and the acceleration in growth rate is the big achievement of economic reforms. With this higher GDP growth India has become the second highest growth rate country in the world, next only to China.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This higher growth rate has been driven mostly by higher domestic investment which in 2007-08 was estimated to be 37.7 per cent of GDP. This higher investment has been substantially financed by domestic saving which was estimated a/36 .4% of GDP in 2007-08. In bringing about this higher growth, privatisation and liberalisation of the Indian economy which were undertaken under the economic reforms started in 1991 have played an important role.

With these reforms India became one of the fastest growing economy of the world. However, it may noted that as a result of world financial crisis (2008-09) which started due to defaults in sub-prime housing loans in the US and spread to all other countries also hit the Indian economy. This adversely hit our exports and also investment in the Indian economy. Therefore, growth rate in GDP fell to 6.7 per cent in 2008-09 but it again went up to 8.6 per cent in 2009-10 and 9.3% in 2010-11.

However, there has been slowdown in overall GDP growth rate after 2010-11. India’s growth rate fell to 6.2 per cent in 2011-12, to 5.0 per cent in 2012-13 and is estimated at 5.3 per cent in 2013-14 (see Table 5.2 and Figure 5.1):

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It is worth noting that services sector in India, like that in most developed countries, is the dominant sector in determining economic growth. The compound annual growth of the services sector was on an average 9 per cent for the period 2004, – 05 to 2011-12 and far exceeded the GDP growth of the industrial and agricultural sectors. I n 2011 -12 and 2012-13 in tune with the general slowdown in the Indian economy, the growth rate of the sendees sector also declined.

The slowdown in growth rate of the services sector in 2011-12 and 2012-13 from the double digit growth of the previous six years contributed significantly to the slowdown in the overall growth of the Indian economy. While some slowdown in growth of services sector can be attributed to the lower growth in agricultural and industrial activities, given the backward and forward linkages with the services, lower demand

from the rest of the world has also played a part.

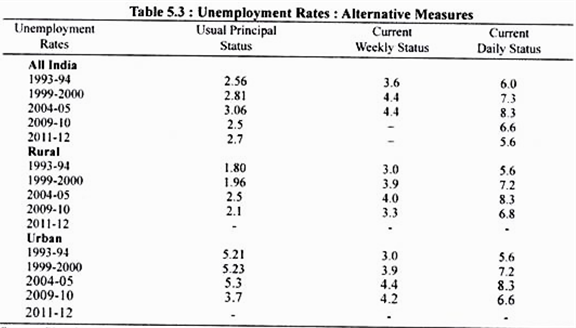

Rate of Unemployment:

The NSS Survey 1999-2000 found that unemployment in 1999-2000 increased as compared to that found in NSS 1993-94. It will be seen from Table 5.3 that all rates of unemployment, namely, usual status, current weekly status and current daily status, (through which

incidence of unemployment is measured in India) increased in 1999-2000 as compared to those in 1993-94.

Further, in the 61st Round (2004-05), the three rates of unemployment further increased in both the rural and urban areas. On current daily status basis in 2004-05 on an average 8.3 per cent persons both in rural and urban areas were found to be unemployed on a day. For All India (both rural and urban) unemployment rate on current daily status basis rose to 8.3 per cent in 2004-05.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This was quite a high rate of unemployment which posed a serious threat to the stability of the Indian society. This high rate of unemployment was only to be expected. The chief drawback of New Economic Policy is that it involves the use of labour-saving modern technology and the competition from the imported products faced by the domestic industries and public sector disinvestment on a large scale. The use of capital-intensive technology not only displaces labour already employed but also lowers the growth of employment from the new investment and capital accumulation.

However, according to 66th round of NSS for the year 2009-10 unemployment on daily status basis has fallen to 6.8% in rural areas and 5.8% in urban areas. For whole India, daily status unemployment fell to 6.6 in 2009-10 per cent from 8.3% in 2004-05 (see Table 5.3). However, doubts were expressed about this fall in unemployment in 2009-10 by many economists including Prof. Amartya Sen.

The government decided to go in for a special unemployment survey in 2011-12. According to this latest data India’s employment rate has declined to 38.6% of population in 2011-12 of labour force from 39.2% in 2009-10. In 2004-05 the employment rate was 42% of population. As a result of this unemployment rate on usual status basis rose to 2.7% in 2011- 12 from 2.5% in 2009-10.

The number of unemployed on usual principal and subsidiary status basis rose to 10.8 million in January 2012 from 9.8 million in January 2010. The special unemployment survey data 2011-12 reveals that only 2.7 million new jobs were created in the five years between 2004-05 and 2009-10 – sharply lower than the 60 million jobs created in the previous five years.

However, according to unemployment survey 2011-12, 14 million new jobs were added in the two years between 2009-10 and 2011-12, nearly five times the jobs added in the previous five years. This is perhaps due to starting of special employment scheme known as MGNREG scheme started in 2009 and also because of higher agricultural growth of 6.6 per cent in 2010-11 and 3.6 per cent in 2011-12.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Surprisingly, unemployment rate on the current daily status basis has also gone down significantly in 2 years period from 6.6% in 2009-10 to 5.6% between July 2011 and June 2012 when the special employment survey was conducted. This indicates more persons were fully-employed, that is, their under-employment sharply declined due to the starting of MGREG scheme. Further, this also seems to be the result of fall in labour force participation rate.

Besides, due to the greater role assigned to the private sector, big business houses, foreign capital (MNCs) the already existing inequalities of income and wealth will further increase. This is against the objective of social justice which in the past was the cherished goal of the Indian planning.

Problem of Poverty:

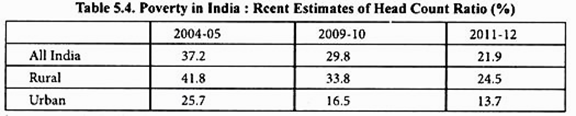

An important consequence of economic reforms is that there has been slowdown in reduction of poverty ratio in the post-reform period despite a much higher growth rate of GDP. On the basis of uniform recall period (URP), percentage of population below the poverty line fell from 36 per cent to 1993-94 to 27.5 per cent in 2004-05 which amounts to 0.74 per cent annual average reduction in poverty.

This is much less than the reduction in poverty ratio in pre-reform period when percentage of population below the poverty line declined from 51.3 per cent in 1977-78 to 38.9 percent in 1987-88 which works out to be 1.2 per cent average annual fall in poverty ratio in these ten years.

However, the estimates of poverty in India has become a highly controversial issue. An expert committee under the chairmanship of Late Prof. Suresh Tendulkar examined the problem of estimation of poverty in India. Tendulkar Committee suggested moving away from calorie intake as the defining parameter for poverty line to a more comprehensive method of using per capita expenditure on basic needs such as food, clothing and services like health and education.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

On the basis of Tendulkar Committee recommendations it was estimated that 29.8 per cent of the population of India was poor in 2009-10 (66th Round NSS) compared to 37.2 per cent in 2004-05 (Note that poverty line in 2009- 10 was fixed at ? 22.4 per capita daily consumption expenditure in rural areas and ? 28.65 per capita in urban areas). The 68th round of National Sample Survey 2011-12 report reveals that there has been not much decline in poverty rate in the urban areas in the two years (2010-12) where industrial reforms have been largely made under the new economic policy adopted since 1991.

We present the poverty estimates based on Tendulkar Committee recommendations for three years 2004-05,2009-10 and 2011-12. On the basis of Tendulkar Committee methodology Planning Commission estimated that poverty came down from 37.2 per cent in 2004-05 to 21.9 per cent in 2011-12. This is based on the poverty line adjusted for price rise between 2004-05 and 2011-12.

In 2011-12, poverty line is fixed at Rs. 27.20 per person per day in rural areas and Rs. 33.4 per person per day in urban area. On this basis, in absolute number of people living below the poverty line declined from around 408 million in 2004-05 to 270 million in 2011-12, that is, about 138 million persons were lifted out of poverty in the seven-year period.

Moreover, from the decline in All Indian poverty ratio from 37.2 per cent in 2004-05 to 21.9 per cent in 2011-12, it has been concluded that poverty in these seven years declined at the rate of 2.2 per cent per annum in these seven years as against 0.74 per cent per annum between 1993-94 and 2004-05

However, these poverty estimates have been criticised on the ground that they have been made on the basis of lower poverty line of daily expenditure per person of Rs. 27.20 for rural areas and Rs. 33.4 for urban areas. The critics have pointed out that, given the high prices of food grains a person cannot possibly live on” Rs. 27.20 in rural areas and Rs. 33.4 in urban areas. Fixing such a low daily expenditure per person for defining poor is making a cruel joke of the poor people.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Besides, it has been alleged that UPA government has made a deliberate effort to keep the number of poor people low to show a big achievement of UPA government. In this context it may be noted that according to World Bank which on the basis of poverty line of $ 1.25 per day (on purchasing poverty basis) estimated that 33 per cent of India’s population was living below the poverty line.

The second controversial point is whether it is rapid economic growth or greater expenditure on social welfare schemes such as MGNREGS that has brought about such a drastic reduction in poverty. Thus it cannot said with certainty that higher rate of economic growth under the economic reforms with its privatisation, liberalisation and globalisation have resulted in slowdown in the rate of decline in poverty ratio.

Volatility in Exchange Rate and Economic Stability:

Another adverse consequence of liberalisation and globalisation is the creation of volatility in foreign exchange rate of rupee which has adversely affected the Indian economy. Under the policy of globalisation of economic reforms we allowed free movements of capital flows into and out of India and switched over to the market determined exchange rate and made the rupee convertible.

From 2003-04 onwards there were large capital inflows into the Indian economy, mainly through portfolio investment by FIIs which caused appreciation of Indian rupee whose value rose from above Rs. 46 to a dollar in 2002-03 and to Rs. 44.27 at the end of March 2006 and further to Rs. 39.4 to a US dollar in mid-Nov. 2007.

This appreciation of rupee adversely affected our exports. Besides, large inflows of dollars got converted into rupees which caused rapid increase in money supply generating inflationary pressures in the Indian economy. Further large capital inflows, especially portfolio investment by FIIs in the Indian stock market, artificially caused high rise in price of shares of Indian companies.

In 2008-09 the opposite happened when due to liquidity crunch in the banking system in the US caused by sub-prime housing loans by American banks and mortgage failures, FIIs started selling shares of the Indian companies held by them and making net capital outflows from India. This led to depreciation of Indian rupee.

The value of rupee which was about Rs.40 to a US dollar in January 2008 depreciated to a low of Rs.50 per US $ in the second week of November 2008 but again appreciated to Rs.45 per US $ in 2009-10 (average of the year). India is at present under flexible exchange rate system under which exchange rate is determined by demand and supply forees. India has experienced high volatility in capital flows which have been the dominant factor in inducing volatility in the exchange rate of the rupee against the US dollar.

The exchange rate appreciated when there were large capital inflows and depreciated when there were capital outflows. Given the stated policy of the Reserve Bank to prevent excessive volatility in exchange rate, it has intervened in the foreign exchange market to buy or sell dollars as the case may be to prevent excessive appreciation or depreciation in exchange rate.

A biggest depreciation of rupee vs US dollar occurred in the month of June to August 2013 when rupee which was around Rs. 56 to a US dollar in the beginning of June 2013, fell to around 60 to a US dollar in the third and fourth week of June 2013 that is, about 7 per cent depreciation in a single month.

This sharp depreciation of Indian rupee was triggered by the announcement by Mr. Bermanke, the Governor of Federal Reserve of the US that it will taper the quantitative easing from the fourth quarter of the year 2013 as the US economy had been revived. This spread a panic in the world capital and foreign exchange markets as under the quantitative easing policy capital outflows were taking place from the US to the emerging economies.

Under the quantitative easing policy the Federal Reserve was buying bonds of $ 85 billion every month and thus pumping money in the US economy to revive it. In the second week of June 2013, the Governor of the Reserve Bank announced that it will reduce the purchases of bonds from $ 85 billion to $ 65 billion per month as the US economy had revived. This caused reversal of capital flows from the Indian economy.

In less than a month over $ 57 billion was withdrawn from the Indian debt and stock markets. This resulted in crash in Indian stock market and led to the increase in demand for US dollars resulting in the rapid depreciation of the Indian rupee. This sharp depreciation of rupee has serious consequences for the Indian economy. Not only will it make our imports costlier and fuel another round of inflation, it will also restrain the RBI from pushing through interest rate cuts urgently needed for kick-starting investment and boosting economic growth.

It follows from above that globalisation with liberalisation of capital flows and market determined exchange rate and convertibility of rupee has caused a lot of volatility in exchange rate and is therefore not without risks and dangers. Therefore, one should proceed with caution in liberalizing capital flows and capital convertibility of the rupee.

Critical Evaluation of New Economic Policy and Economic Reforms:

The supporters of new economic policy and economic reforms who argued for diluting the role of public sector or Government as it does not ensure efficiency in production laid great stress on ‘Government failures’ for promoting economic growth. They however turn a blind eye to the market failures.

To quote an eminent American economist Dr. Joseph Stiglitz, who has won Nobel Prize for Economics in recent years, “Market failures are a fact of life, as are government failures. New liberal ideologies assume perfect markets, perfect information, and a host of other things which even the best performing market economies cannot satisfy”. He therefore forcefully argues for a balanced approach to government and markets recognising that both are important and complementary”

.This means both public sector and private sectors should play a complementary role in bringing about economic growth. Due to market failures we cannot rely on private sector alone to bring about sustained economic growth and adequate expansion in employment opportunities and for eliminating poverty.

It is not being argued here that we should go back to ‘license-permit Raj”. What we are stating is that (1) markets need to be regulated effectively by the Government if the objective of growth with equity is to be realised. Stock market scam of 1992 prompted by Harshad Mehta and the stock market scam of 2001 engineered by Ketan Parikh are shining examples of the absence of effective regulation of the market by the Government playing havoc with the economy. Again, UTI fiasco of July 2001 suspending the sale and re-purchase of US-64 units showed that activities of mutual funds must be effectively regulated and not left to the free working of markets.

That there is need for regulating the market economy and intervention by the Government to revive it has been clearly evident from the financial crisis that gripped the world economy in 2007-09. This financial crisis originated from the defaults of sub-prime housing loans given by the American banks but due to the integrated nature of world economy today engulfed the whole world.

This financial crisis seriously affected the American banking system with some American banks going bankrupt. The collapse of the American banking system created liquidity crunch for the corporate sector affecting investment and creating conditions of recession in the American economy.

Due to the integrated nature of the world economy, the American financial crisis not only affected the corporate sector in the US but also created global meltdown involving not only European countries but also Asian economies (including the Indian economy).

To bail out the American banks, the President Bush came out with 700 billion US dollars plan to help them solve the liquidity problem and restore investors confidence so that the American economy could be revived. This means that now a lesson has been tenant that the market economy is not self- correcting and as emphasized by J.M. Keynes in the early thirties that in situation of recession the Government has to intervene in the economy through expansionary fiscal and monetary measures to overcome recession.

Thus the recent global financial crisis (2007-09) has demonstrated that markets are not self- correcting, do not allocate resources efficiently and serve public interest well. The financial crisis that emanated from the US had the roots in massive allocation of resources to housing. When the prices of houses fell sharply, households defaulted in making payments of loan installments. As a result, millions of families who could not afford them were forced out of their homes. Thus this was great failures of market which led to the financial crisis in the US and spread to other countries of the world.

Since the integration of Indian economy with the world economy as the result of economic reforms aimed at liberalisation of trade and capital flows, the global financial crisis spilled over into the Indian economy as well. The Indian stock market crashed causing crores of losses to the investors. This greatly affected investors’ confidence. The shares of banks had been affected most and as a result the capital outflows by FIIs from India not only affected share prices but also caused liquidity problem for the banks and the corporate firms as FIIs converted rupees into dollars which they sent back to meet the liquidity requirements of their present companies.

This liquidity crunch for the banks and corporate sector adversely affected the investment environment in the Indian economy. To bail out the banking system and stock market, RBI over different phases reduced cash reserve ratio from 9 per cent to 6.5 per cent and thereby infused Rs.14,000 crores liquidity into the market to prevent much slowdown in India’s economic growth.

The upshot of the argument is that market economy is not self correcting and therefore there is need for effective regulation and intervention by the Government to ensure not only the stability of the economy but also to sustain the growth moment of the Indian economy.

Apart from regulation of markets and private sector what is needed in the context of the Indian economy is the paramount role of Government in stepping up public sector investment in infrastructure if sustained rate of higher growth rate on sustained basis is to be achieved. Government role is also crucial for adequate investment in social sectors such as education, health care and poverty alleviation programmes which are generally neglected by the private sector.

For the purpose of poverty alleviation, undertaking of rural public works to utilize not only accumulated food stocks but also to generate employment opportunities for the poor and unemployed is of paramount importance for which the Government should increase its expenditure.

For the purpose of investment in infrastructure and social sectors (education and health care) and expenditure on employment schemes for the poor the Government should not hesitate to incur moderate fiscal deficit. In this way if there is a moderate increase in fiscal deficit, it should not be considered undesirable. We should not follow unthinkingly IMF inspired policy of reducing fiscal deficit under all circumstances.

In our view reduction in fiscal deficit should not be elevated to a dogma. What is relevant is that Government should spend its borrowing for investment purposes, especially infrastructure and on development of human capital – education and health care. What is needed is that Government should not borrow for consumption purposes.

Prof. Amartya Sen rightly writes that “the success of liberalisation and closer integration with the world economy may be severely impaired by India’s backwardness in basic education, elementary health care, gender inequality and limitations of land reforms. While Manmohan Singh did initiate the correction of governmental over-activity in some fields, the need to correct the governmental under-activity in other areas has not really been addressed.

Further, referring to the higher growth rate in some East and South East countries which have achieved high growth rate with considerable equality he writes, “These countries all share some conditions that are particularly favourable to widespread participation of the population in economic change. The relevant features include high rates of literacy, a fair degree of female empowerment, and quite radical land reforms. Can we expect in India results similar to those that the more socially egalitarian countries have achieved, given that half the Indian population (and two-thirds of the women) are still illiterate, that female empowerment is very little achieved in most parts of India, that credit is very hard to secure by the rural poor, and that land reforms remain only partially and unevenly implemented? Should we not have expected more in the direction of breaking the terrible neglect of these concerns, on which the basic capabilities of the Indian masses depend?”

Commenting on the supporters of policies of free market, liberalisation and Washington Consensus Stiglitz writes that these policies “worked badly for developing countries. They were told to stop intervening in agriculture thereby exposing their farmers to devasting competition from the United States and Europe. Their farmers might have been able to compete with American and European farmers but they could not compete with US and European Union subsidies. Not surprisingly, investment in agriculture in developing countries faded and food gap widened”. As a result, according to him, policies of neo-liberalism will lead to a large rise in poverty.