The following points will highlight the three main components of balance of payment.

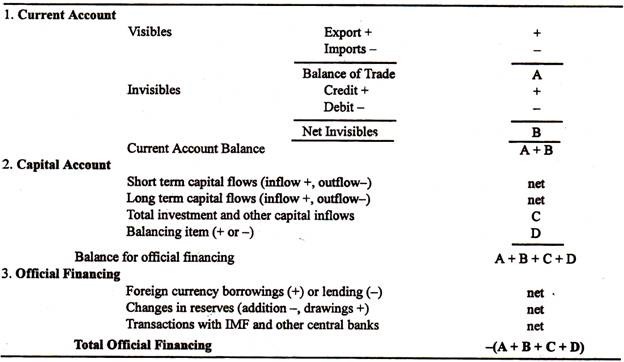

The three main components are: 1. Current Account 2. Capital Account 3. Official Financing.

The addition of the totals on current and capital account equal the total for official financing. Thus, if in Table 21.1 A + B + C + D = Rs. 3,000 crores, this amount would be added to the reserves or repaid to borrowers and the official financing figure would be Rs. 3,000 million (in this part of the accounts the minus represents a gain!).

Table 21.2: Balance of Payments Accounts:

Component # 1. Current Account:

This part of the balance of payments is regarded as the most important, as it shows a nation’s trading strength. If payments are greater than receipts, there is a deficit which is undesirable.

This account is subdivided, as shown in Table 21.1, into:

1. Visible Trade — trade in goods

2. Invisible Trade — trade in services.

A — Visible Trade:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The money earned from Indian exports of goods (e.g., cars sold to Nepal) is credited (added) to this account, whilst payments for imported goods (e.g., American aircraft sold in India) are debited. The difference between the totals is known as the Balance of Trade.

B — Invisible Trade:

The income earned from the sale of Indian services abroad is known as an invisible export, e.g., an insurance premium paid by a British ship-owner to an Indian broker. When Indian residents spend money on foreign services, e.g., a week’s accommodation in London, they are creating invisible imports, because payment is going out of India.

The main invisibles are as follows:

1. Government expenditure:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Government expenditure on embassies, contributions to IMF or ADB and other international bodies, military bases/forces abroad, and overseas aid. All these create a substantial deficit.

2. Interest, profits and dividends:

The earnings from loans, companies and shares, respectively, earn substantial surpluses for the Indian economy.

3. Other financial services:

The earnings of solicitors, brokers, merchants and pensioners also contribute benefits to the invisible account.

4. Transport:

The earnings on passenger carrier by sea and air are two major items.

5. Tourism:

This covers the expenditure of travellers abroad.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

6. Private transfers:

Individuals transfer money to other countries. Most industrialised nations contain migrants who remit fluids to relatives in their family of origin.

A + B — Current Account Balance:

The balance of trade (visible) and net invisibles are added, as in Table 21.1, to give, the current account balance. The net figure may be plus or minus. A deficit (-) on the current account is a warning that the nation is spending more than it is earning, in the short run.

Component # 2. Capital Account:

C — Investment:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This account includes investment and other capital movements. Outflows create deficits (-) and inflows give surpluses (+) in the account. For instance, if an Indian trader purchases a new shop in London, this is an outflow of capital. Conversely, if Toyota (Japan) builds a showroom in Bangalore, then there is a capital inflow.

Expenditure on portfolio (paper) assets is also included in this selection of the accounts. Thus, if an Indian citizen buys shares in McDonald’s or General Motors (USA) this counts as a capital outflow.

The investment can also be distinguished between private and public sector. Private sector investment tends to be in buildings and paper assets held for a long period of time. Public investment, on the other hand, consists of low interest loans to underdeveloped nations (i.e., aid) where the aim is not always profitability.

Capital flows may be short-term or long term. The short-term ones tend to be unpredictable and volatile. They feature the shifting of very liquid assets (i.e., ‘hot’ money) between nations to gain the advantage of favourable interest-rate differentials.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the short run, net inward investment benefits the balance of payments accounts because official financing is not needed — reserves can be accumulated and borrowing repaid. However, in the long run, it may be harmful. The profits, interest and dividends from the investment are remitted abroad and become invisible imports, thus weakening the current account.

D — Balancing Item:

This is an accounting device to cover errors and omissions. A balancing figure is added to — or subtracted from — the combined balances of the current and capital accounts. The balance of payments accounts always balance because the current and capital account totals together equal the official financing undertaken. As the latter figure is more accurate than the varied data in the other two accounts, the balancing item is calculated from it and is used to make the two totals the same. It is a net figure.

Component # 3. Official Financing:

The Balance for Official Financing (which used to be termed Total Currency Flow) shows the balance of monetary movements into and out of the country. A positive figure reveals a net inflow of funds into a country. Alternatively, a net outflow is represented by a negative figure.

When there is a negative figure, the amount has to be paid for either by:

(a) borrowing from other central banks and international organisations, or

(b) using up reserves which have been saved over the years, or

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) borrowing and withdrawing reserves.

When the balance for official financing is positive, then loans can be repaid and reserves replenished. Governments do sometimes borrow even when the balance for official financing is positive; this is in order to build up reserves for the future.

The fact that the amount of official financing equals the balance for official financing ensures that the balance of payments always balances.

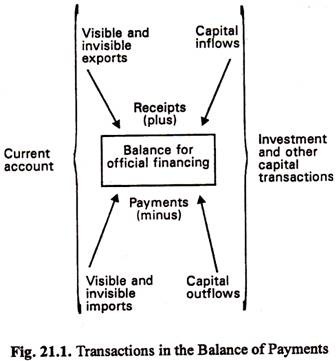

So, through official financing, the account as a whole is brought into exact balance (Fig. 21.1). This is why it is said that the balance of payments always balances.

A country has a balance of payments problem when a section of its accounts are in regular deficit or surplus. Deficit problems are more serious than surplus ones, as surpluses usually result from successful international trading, whilst deficits indicate failure. Persistent imbalances indicate that the balance of payments is in fundamental disequilibrium. This usually requires the government to undertake remedial measures.