The following article highlights the top six theories of wages .

Theory # 1. Money Wages and Real Wages:

What the labourer earns by working in a factory or office is called wages. The labourers are generally paid a certain sum of money per day or week, etc.

The amount of money paid is called the money wages. The worker however, is more interested in the goods and services which he can get with his money wages or otherwise. The amount of goods and services which the labourer actually gets is called his real wages. The standard of living and the prosperity of a labourer depends not on his money wages but on his real wages.

Real wages depend upon the following factors:

1. Price Level:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The labourer uses his money wages to purchase his requirements. The amount of goods and services that he can get depends on the level of prices.

2. Extra Earnings:

It is possible for labourers to get extra earnings. For example, waiters in hotels get tips which supplement their wages.

Sometimes labourers are given food and lodging either free or at a reduced rate. Such things must be counted as part of their real wages. Sometimes labourer has to incur some costs in carrying out his duties. For example, a day labourer has to incur transport costs when going to his place of duty. Such costs must be deducted from his money wages when calculating his real earnings.

A major problem connected with wages is the apparent discrepancies which often exist in the payments of workers in various occupations. For example, a worker living in an area where the cost of living is high will find his pay packet of less real value to him than the worker earning the same amount of money but residing in a cheaper area. Thus, it may be necessary to pay higher wages to persons employed in Calcutta than to those in Burdwan or Bandel, although the ‘real’ value of the wages of the Calcutta worker, in terms of what the wages will buy, will be no higher.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Wages also differ due to a number of factors. Any comparison of wages may thus involve taking into account such factors as subsidized housing, pension rights, family allowances, expense sheet allowances and the use of company cars. These extra payments will, of necessity, have to be taken into account along with other factors like, security against unemployment, long-term promotion prospects and the job-satisfaction of the work itself. All these add up to make ‘real wages’ of a job very different, in many cases, from the purely ‘money wages’.

Theory # 2. Marginal Productivity Theory of Wages:

The most important theory regarding wage determination is the marginal productivity theory. It was developed by J. B. Clark at the end of the 19th century.

The marginal productivity theory is basically a theory of demand for labour. It is based on the proposition that labour is in demand because it is productive, i.e., because it can be used to produce commodities which are in demand. The theory explains how a profit- maximising firm takes decision regarding the optimum purchase of labour, the price of which is market-determined and is taken as given.

Assumptions:

The marginal productivity theory of wages is based on a number of assumptions. Economists normally make the following assumptions:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Buyers and sellers are price-takers and each one is fully informed about the price and quality of labour. In other words, the labour market is perfectly competitive.

2. Labour is homogeneous, i.e., there is no difference in ability or any other characteristics between one worker and another.

3. Wages fluctuate so as to equate the demand for labour with its supply.

4. There is perfect mobility of labour, i.e., there are no barriers to movement of labour between regions of the country, occupations and industry.

5. The marginal product of a labour can be (numerically) measured or calculated.

6. Employers use labour with a view to maximising profits. Similarly, workers tend to work in industry where wages are the highest.

Demand for Labour by a Firm:

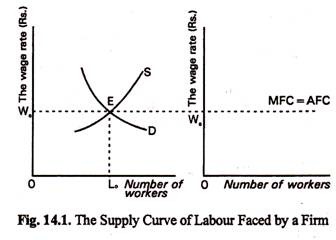

Since the MP theory assumes the existence of pure competition in the labour market the market supply curve of labour is elastic at a particular wage, i.e., the market-determined wage. Suppose it is Rs. 30. Now a profit- making firm will be faced with a completely elastic supply curve of labour as is shown in Fig. 14.1.

If the supply curve faced by a firm is completely elastic, an individual firm has to accept this wage as a price-taker. So it has to take only one decision in order to maximise profit: optimum purchase of labour at this wage.

So the question is:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

What determines an individual firm’s demand for labour? In considering what commodity to produce and how much of it to produce the entrepreneur compares marginal cost and marginal revenue. In a like manner, with respect to labour, when deciding how many people to employ, the entrepreneur will compare what he has to pay with what he will get in exchange. If he is thinking of employing one extra worker, he will want to know whether the extra worker will add more to revenue than to cost.

Marginal Revenue Product:

The extra revenue obtained by the entrepreneur by employing one extra worker is known as the ‘marginal revenue product’ (MRP) of labour. Similarly, the wage that has to be paid to this worker is called marginal cost of labour. It is quite obvious that the entrepreneur will not be desirous of paying that worker a wage which is greater than the MRP. Under perfect competition, if the entrepreneur wishes to maximise profits, he will employ labour up to the point where the wage is equal to the MRP.

Two Components of MRP:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) the marginal physical product (MRP) and

(b) the price at which the firm’s output is sold.

The MPP shows how much has been added to total output by the employment of one extra worker.

Thus, under perfect competition (where MR = P):

ADVERTISEMENTS:

MRP = MPP x Price of the product

Suppose 10 workers produce 30 units of output. When 11 workers are employed output increases to 32 units. So MPP is 2 units of output. If the price of the product is Rs. 6 per unit, the firm makes an extra revenue of Rs. 12 (= 2 x Rs. 6) by selling the output produced by the last worker. This is MRP.

Diminishing MRP:

However, as more and more workers are employed in the production process, keeping the amount of other factors fixed, the contribution made by every extra worker will fall after a certain point. This is due to the operation of the Law of Diminishing (Marginal) Returns.

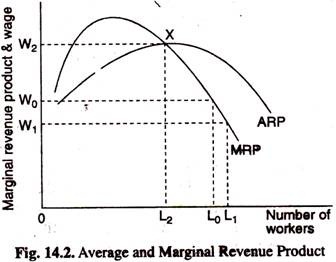

However, due to the existence of perfect competition in the product market the price of the product remains unchanged. So the MRP (which is the product of MPP and price) will fall and the MRP curve will be downward sloping. This is shown in the diagram (Fig. 14.2). In Fig. 14.2 we also show the average revenue product (ARP) curve. The relation between MRP and ARP is the same as the relation between MPP and APP Here ARP=APP x P.

A firm reaches the point of optimum purchase of labour when MRP = the market wage (or the marginal cost of labour). Here the section of the MRP curve which lies below the ARP curve in Fig. 14.2 is indeed the firm’s demand curve for labour (if we measure market wage along with marginal revenue product on the vertical axis). When the market wage is W0 the number of workers employed is OL0 (because the wage will then be equal to MRP). If the wage rate falls to OW1 the number of workers employed will increase to OL.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, that part of the MRP curve which lies above the ARP curve is not part of the demand curve for labour. If, for example, the wage rate were OW2, total wage payment (OW2 x OL2) would exceed total revenue (OL2 x L2X). In such a situation the firm would close down its operations completely because it would not be making even normal profits.

Therefore, only that part of the MRP curve which lies below the ARP curve is the demand curve for labour. In Fig. 14.2, this demand curve, like the demand curve for a product, is downward sloping. It slopes downward from left to right. The implication is simple – the lower the wage, the greater the number of workers employed.

Criticisms of the Theory:

The marginal productivity theory of wages has been criticised on the following grounds:

1. Firstly, the theory is one-sided because it focuses on the demand side of the labour market to the complete exclusion of the supply side. But in practice we observe that wages are determined by the forces of both demand and supply. So the theory is incomplete, too.

2. Secondly, according to this theory, wages can never be more or less than the marginal product of labour. But, in practice, we observe that trade unions often demand and succeed in getting wages beyond the marginal product of labour. Likewise, the absence of labour unions creates situations where wages are far less than the marginal product of labour. In fact, wages are not always determined by market forces. Instead, wages are fixed by collective bargaining between the trade union and the employer.

3. Thirdly, the theory is based on the assumption of perfect competition in both labour and commodity markets. If we relax the assumption in any one of the markets the major conclusion of the marginal productivity theory will not hold. Since perfect competition does not exist in most real life markets the marginal productivity theory is unrealistic.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. Fourthly, the forces of competition lead to the equalisation of marginal product among different sectors or industries. Critics point out that the theory offers only a long-term explanation of the determination of wages. It fails to explain how wages are determined in the short run.

5. Fifthly, the theory is based on a number of unrealistic assumptions. Firstly, the theory assumes that all workers are alike in skill, ability and efficiency, or, in other words, all units of labour are homogeneous. But, in practice, we observe that workers differ in ability, efficiency and productivity. This largely accounts for inter-individual difference in wages and earnings.

6. Critics also point out that when production is carried out on a very large scale it becomes very difficult — if not absolutely impossible — to measure the marginal product of labour.

In large production units, the employment of one extra worker makes hardly any difference to the total product. Thus, we cannot arrive at an accurate estimate of the marginal product of labour.

7. According to this theory, wages depends on the (marginal) product of labour. Critics point out that the converse is also true. Labour productivity also depends on wages. It is in this context that Alfred Marshall spoke of the economy of high wages. According to Marshall, high wages promote efficiency; low wages retard it. If the wage rate is reasonably high or fair enough the standard of living of the workers will also be high. Consequently, the productivity of labour will rise. In this case, productivity is influenced by wages.

8. Moreover, marginal product of labour depends not only on the usage of labour but on the supply of complementary resources such as land, capital, etc. Thus, the efficiency of a worker depends, at least partly, on the amount of resources he has to work with. If the supply of other resources is quite abundant and that of labour is scarce, the marginal product of labour will be very high indeed. The converse is also true. If a worker does not have sufficient amount of other resources, his efficiency and, hence, productivity are bound to be low.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

9. Critics also point out that the (marginal) product of labour also depends upon the efficiency or inefficiency of management. An otherwise efficient worker will not be able to deliver the goods if he has to work under an incompetent manager. (This is usually found in most public sector undertakings.)

10. Finally, we may note the marginal product of labour can be measured only when a worker is actually employed in the work place. So the question is: how to employ a worker on the basis of his marginal product? The marginal productivity theory leaves this question unanswered.

Conclusions:

For all these defects the marginal productivity theory is not considered to be satisfactory as a determination of the wage rate in a free market. So other theories have also been developed.

Thus the conclusion is that MP theory of wages is not quite satisfactory. There is no doubt a relation’ among the rate of wages, MRP and the number of persons employed. Thus, the MRP is a rough and ready measure of the rate of wages, not its determinant.

Theory # 3. The Demand and Supply Theory:

To sum up, the marginal productivity of labour alone does not determine the rate of wages. It simply sets the maximum limit of wages; the minimum limit is set by the standard of living of the workers. The employers try to pay less than the marginal product of labour and the workers try to get more than the cost of living. The actual rates are determined between these two limits, depending on the relative strength of the employers and the workers’ organisations.

The wage-rate in a particular industry is determined by the demand for and the supply of labour. Labour is demanded because of its productivity and so the employer demands the labour up to the level at which the wage-rate is equal to the value of the marginal product of labour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

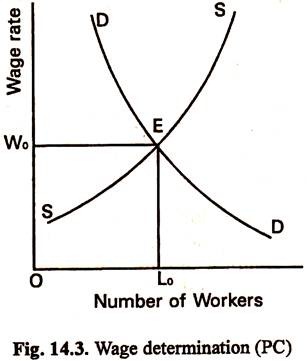

The supply of labour depends, on the other hand, on its supply price, which depends on the standard of living of the workers, the strength of trade unions and various other factors. The workers supply their labour up to the point at which the rate of wages becomes equal to the cost of living. The equipment rate of wage established when the demand for labour is equal to its supply. This point is illustrated in Fig. 14.3.

In Fig. 14.3 DD is the demand curve for labour and SS is its supply curve. When the wages become OW0 or EL0, the demand for labour becomes equal to its supply. So OW0 or EL0 is the equilibrium rate of wages under pure competition and the number of labour employed is OL0.

Theory # 4. The Supply of Labour:

One of the major defects of the marginal productivity theory of wages is that it ignores the supply side of the labour market. But a study of the nature of labour supply is important because it is different from the supply of other factors.

The term ‘supply of labour’ may refer to either of the following:

(a) The supply of labour in the country as a whole;

(b) The supply of labour by an individual worker, and

(c) The supply of labour for a particular job.

An Individual‘s Supply of Labour:

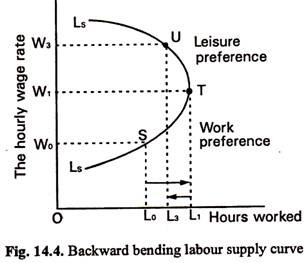

If an individual is permitted to choose the number of hours he works, his supply curve of labour will be backward bending, as has been shown in Fig. 14.4. Why is it so? This is explained by two effects of a rise in wages— the substitution effect and the income effect. We may first discuss the nature of substitution effect.

As the wage rate rise from W0 to W1 the worker decides to work more (i.e., for longer hours per day). Consequently, the number of hours worked increases from OL0 to OL1. This is because he is losing more money now by sitting idle — leisure time has become more expensive. Leisure will, therefore, be substituted by extra work.

However, if the wage rate continues to rise a strange thing happens. Here in Fig. 14.4 the supply of labour is maximum when the wage rate is OW1. This may be called the optimum wage because it ensures maximum labour supply. However, if the wage rate goes above OW1, the income effect becomes stronger than the substitution effect. A rise in wages is equivalent to a rise in the income of the worker.

Thus, the worker can earn the same amount of money as before by putting less effort. In the past the worker might have put extra effort in order to buy more things for himself and his family, e.g., tape recorders, TV sets, refrigerators. Now he takes advantage of the further increase in wages to take more time off in order to enjoy what he has bought.

In other words, as the income of the worker has gone up, he may prefer to enjoy certain superior goods which he could not previously afford (viz., leisure). Because his income has increased, he can now afford to buy more leisure, i.e., work fewer hours each week or enjoy paid holiday (by taking a day off more often). He is no longer interested in over-time work or leave encashment.

Theory # 5. Trade Union and Wages:

A trade union is defined as a ‘continuous association of wage-earners for the purpose of maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment’. (Sydney and Beatrice Webb).

The functions of the trade union are usually classified under two broad heads:

(i) Militant functions:

Trade unions organise strikes and other movements to increase the wages and other allowances (like bonus and gratuity, profit sharing, dearness allowances, medical allowances, etc.), to fight against the unjust treatment of the employers for increasing the share of the labour in the national income.

(ii) Fraternal functions:

These functions relate to the promotional activities of the trade union. These include the arrangement for education, amusement, recreation, medical facilities, training arrangement, and financial assistance to the needy members, etc. for the workers. These functions increase the efficiency of labour and promote their welfare.

But the main concern of trade unions is with the question of wages of the labourers. Trade unions try to raise wages through negotiations or movements.

Collective Bargaining:

Collective bargaining is an important method of negotiation between the representatives of the employer and the representatives of one or more trade unions representing the employees, mainly for the fixation of the rates of pay and conditions of work. It may also be used for settling day-to-day minor labour dispute. It may take place at plant, company or industry level — the aim being to reach an agreement acceptable to both parties.

Collective bargaining is an effective means for defining the respective rights and obligations of management and labour. It is also helpful in building up a strong and healthy trade union movement. Again, with the growth of trade union movement this method gains importance for preparing the ground for mutual settlement of disputes. It establishes bilateral monopoly in labour relations.

The effects of the collective bargaining upon wages and employment of labour depend on the level where the rate of wages is fixed through collective bargaining. Besides, the success of this method presupposes strong trade unionism and the close cooperation of the state, employer, labour and the general public—which may be lacking in a less developed country like India.

Theory # 6. Relative Wages (Difference in Wages):

It may be noted that in the real world there is no single price of labour. For example, there is a market for typists, another for bakers, yet another for carpenters and so on. Wages do differ for different jobs. This is because the market for labour is not a single market.

There are different markets for the different types of jobs in each market—if there is a competitive situation—the price, i.e., the wage, is determined by the demand for and supply of that particular type of labour.

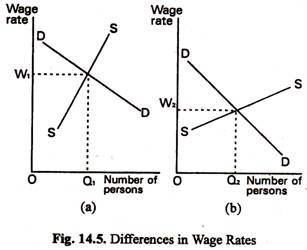

In order to determine the wage rate for a particular occupation, the demand and supply curves are brought together and the wage rate settles where the two curves meet, i.e., where demand and supply are equal. Thus, in Fig. 14.5, where the two diagrams represent the markets for two different types of labour, the wage rate in (a) settles at OW1 while in (b) it will be OW2. Changes in demand or supply will bring about changes in wages.

If there is perfect competition in the labour- market (i. e., if labour is homogeneous, implying that all workers are alike in skill, ability and efficiency) and workers are mobile, the forces of competition would lead to equalisation of wages.

Workers from low paid jobs will be attracted into high paid jobs. The supply curve in (a) will shift to the right and that in (b) to the left. As a result, the wage rate in (a) will fall and that in (b) will rise. As the process continues, wage rates for different occupations will tend towards equality.

However, there are various obstacles (barriers) to labour mobility. Anything which hinders such mobility will affect changes in labour supply in different occupations which are needed to equalise wages.

But this does not happen for a number of reasons. The labour market is imperfect because of the existence of trade unions. Trade unions may demand and succeed in getting higher wages even when there is no excess demand for labour (there may, instead, be an excess supply). Trade unions may restrict the supply of labour to raise wages.

Another factor accounting for differences in wages is indicated by the shape of the supply curves in Fig. 14.5. In diagram (a) supply is more inelastic than in diagram (b). It may thus be difficult for a higher wage to lead to an increased supply of labour in (a) as it would in (b) Diagram (a) could represent occupations which requires a great deal of skill or a long period of training or both. In fact, occupations differ in their training requirements and in the need for applicants to possess special aptitudes to follow them successfully.

Similarly, a person (such as a technical supervisor) may spend five years servicing an apprenticeship in order to acquire a skill. Only those with sufficient mental capacity, perseverance and character are likely to succeed and the supply of such persons relative to the demand is low. Hence the price of their services is high. By contrast, diagram (b) could represent the market for unskilled manual jobs where little or no training is required.

The supply of labour for unskilled and semi-skilled occupation requiring no special qualifications except good health is much larger, so that, sometimes, supply may exceed demand and wage rates are relatively low. It is virtually impossible for numerous unskilled workers to move from manual work and become lawyers, doctors or school teachers in order to get high wages and to equalise the wage rates in the different occupations.

It is, therefore, clear that the supply of labour to some occupation is limited by the natural ability which is required. For example, top sports persons, like P. T. Usha, earn large sum of money and will continue to do so because the supply of natural athletic talent is limited. Thus, where a special talent is necessary for success as in the case with film stars, singers and cricketers, little can be done to increase supply. Thus, persons possessing a unique talent can earn very large sums of money because of the scarcity value.

However, it is enough to have exceptional talent in order to earn an exceptionally high income. It is necessary also to have those particular talents which are most in demand. The most financially successful workers are those who can provide the services for which consumers are willing to pay and not those which are the most deserving of reward. Job also differs in responsibility (e.g., a police inspector earns more than a sergeant, who, in turn, earns more than a constable).

Non-Monetary Advantages:

Some occupations offer certain non-monetary advantages. For example, some kinds of work are more congenial than others (as is desk job) and are earned on under pleasant conditions (sitting in an A.C. chamber). In some jobs (as in teaching) the employee enjoys a greater degree of independence than others.

Another factor may be high job security (as in government services). Football players and coaches may earn high wages but may be out of work for long periods. Some occupations offer other material rewards beside the money wage, such as free or subsidised lunch, or the use of a company car.

In contrast, jobs such as ditch-digging are unpleasant; some, such as mining, are dangerous (compared with sitting in an office); and others involve various degrees of inconvenience such as shift working, absence from home and working at weekends or public holidays (as in the case of GKW employees). In general, the greater the non-monetary advantages of a job the greater will be the supply of labour and, hence, the lower the wages. On the other hand, the more unpleasant or inconvenient the occupation the fewer there will be who will wish to enter it and, hence, the higher the monetary rewards.

Differences in Earnings within the Same Occupation:

Wages for people doing similar jobs may differ due to two factors (a) wage drift and (b) the geographical immobility of labour.

Wage drift raises earnings on a local basis in areas where there is shortage of labour. It is, therefore, a means of attracting labour to an area.

In fact, there may be differences in wages between different regions because of differences in the cost of living between those regions. For example, in many jobs, workers in Bombay receive an additional allowance because the cost of living there is higher than in other parts of India.

However, a higher level of earning may fail to attract workers because of obstacles hindering their easy movement from one area to another.

Some of the restricting influences are:

(a) Changing jobs may cause considerable inconvenience. It may mean uprooting a family from accustomed surrounding and old friends to start a new life in an unknown place.

(b) A change may be costly. The costs of selling one house and buying another may be sufficiently high to deter moving to a new area.

(c) There is a risk that the relatively high earnings in an area may be only temporary.

As a result of all these factors, differences in earnings exist among workers of the same occupation, in different industries and in different places of the country.