There are a number of theories to explain the nature and determination of the rate of interest. The main theories are:

1. Marginal Productivity Theory:

This theory simply states that the marginal productivity of capital determines the rate of interest.

Interest is paid because capital is productive and is equal to the marginal product of capital. In the modern complex production system, the role of capital is very important as a producer can produce a much larger volume than what can be produced without capital.

Accordingly, the higher productivity of capital makes the interest higher. The converse is also true. So, a producer would employ capital up to that amount at which the rate of interest becomes equal to the value of the marginal product of capital.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, like the marginal product of other factors, the marginal product of capital cannot be separately determined as every product is jointly produced by all the factors. Further-more the theory is one-sided as it emphasises only the demand side of capital for the determination of interest. Finally, the use of capital does not always increase total production as assumed in the theory.

2. Demand and Supply Theory:

According to this theory, the demand for and the supply of capital jointly determine the rate of interest. The demand for capital is governed by its marginal product and the supply of capital by waiting or saving.

The rate of interest comes to the equilibrium position at the level at which the demand for capital becomes equal to its supply. But the theory is criticised on the ground that it assumes the existence of full employment which is a myth. Moreover, it fails to take into account the effect of changes in investment upon the level of income and savings.

3. Abstinence or Waiting Theory:

This theory holds the view that interest is the reward for the abstinence from the present consumption. People save to create capital- goods, but saving implies the abstinence from, or the sacrifice of, present consumption. The abstinence is, however, unpleasant. Most people do not like it. So interest must be paid to induce the people for making the sacrifice of the present consumption.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But the abstinence theory is criticised on the ground that abstinence does not always involve sufferings. A rich man does not suffer any loss or bear any inconvenience when he saves money and lends it for earning interest. Moreover, interest cannot be regarded as the price paid for waiting because many people lend money without getting any interest.

4. ‘Agio’ or the ‘Time Preference’ Theory:

According to the Austrian economist Bohm- Bawerk, interest is the agio or premium which the present consumption has over the future consumption of the same amount. Later on, Fisher developed the time-preference theory on the basis of the agio theory. According to him, interest functions as a price in exchange between present and future goods.

As he put it, “The theory of interest is one of investment opportunity and human impatience as well as exchange.” Most people prefer present consumption over the same amount of future consumption. So interest has to be paid to win over the individual’s impatience to spend his income for present consumption in preference to future enjoyment. But this theory is one-sided as it has explained only the supply side of capital.

5. Loanable Funds Theory:

The neoclassical writers hold the view that the rate of interest is the price for the use of loan-capital and is determined by the demand for, and the supply of, loanable funds.

6. Liquidity-Preference Theory:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to Lord Keynes, the rate of interest is determined by the demand for and the supply of money. Interest is the reward for parting with liquidity for a specified period of time.

The last two theories are the most important ones and may now be discussed in detail.

The Loanable Funds Theory:

The rate of interest is price paid for using someone else’s money for a specified time period. According to Dennis Roberston and neo-classical economists this price or the rate of interest is determined by the demand for and supply of loanable funds. The market for loanable funds consists of arrangements and procedures to carry out transactions between people who want to borrow money and people who want to lend money.

Demand:

The demand for loanable funds originates from two basic units of the economy— consumers and business firms.

(a) Consumers demand loanable funds because they prefer current goods to the same amount of future goods. According to Bohm-Bawerk, on average, people have a positive rate of time preference.

This simply means that people subjectively value goods obtainable in the immediate or near future (including the present) more highly than goods obtained in the distant future. Most people would prefer to have a new television set today rather than the same or a better set after ten years.

There is nothing unusual about a positive rate of time preference. In a world characterised by uncertainty most people prefer the reality of current consumption to the uncertainty of some large amount (in physical or monetary terms) of future consumption. As the old saying goes: “A bird in hand is worth two in the bush.” Consumers are also ready to pay interest for earlier availability of durable goods like cars or refrigerators. Thus, from consumers’ point of view, interest is the cost of easier and earlier availability of goods.

(b) Business firms or investors demand loanable funds because they are a form of capital (i.e., money capital). Capital is demanded because it is productive. Capital makes other factors more productive. In other words, investors demand loanable funds so that they can invest in capital goods and finance roundabout methods of production. Such methods of production are usually more productive than simple methods of production. Since roundabout methods of production often make it possible to produce a larger output at a lower cost, investors can gain, even if they pay interest to purchase the machines, buildings and other resources required by the production process.

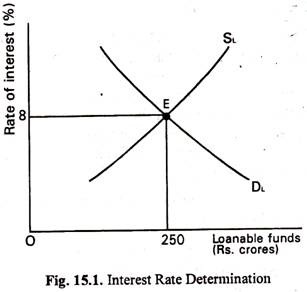

Thus, an investor’s demand for loanable funds arises due to the productivity of the capital investment. An increase in the rate of interest is, in essence, an increase in the cost of larger availability of consumption goods made possible by a machine. As Fig. 15.1 shows, consumers and investors would borrow more at low rates of interest (or curtail their borrowings in response to increase in the rate of interest). Likewise, some investment projects that would now lead to gain at a lower interest rate will not be profitable at higher rates. Thus, the amount of loanable funds demanded varies inversely with the rate of interest.

Supply:

Even though higher interest rates lead to a fall in the amount of borrowing by consumers and investors, they encourages lenders to make a larger volume of funds available to the market. Even individuals with a positive rate of time preference will curtail current consumption to supply more loanable funds in the market if the rate of interest is reasonably high or sufficiently attractive.

People, no doubt, prefer current (earlier) consumption to future (deferred) consumption. But they also prefer more goods to few goods. So they are ready to sacrifice current consumption if they expect to get more consumption goods in exchange at some future date.

A rise in the rate of interest increases the quantity of future goods available to people willing to sacrifice current consumption. This increase in the quantity of future goods that can be acquired for each rupee supplied can be showed on a supply curve that slopes upward from left to right.

In Fig. 15.1, the demand curve for loanable funds intersects the supply curve at point E and the equilibrium rate of interest (8%) is automatically determined (by market forces). The interest rate (8%) brings the plans of borrowers in harmony with the plans of lenders. In equilibrium, the quantity of funds demanded by borrowers is equal to the amount supplied by lenders (Rs. 250 crores) as Fig. 15.1 shows.

Criticisms:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Three major criticisms of the loanable funds are:

1. The classical writers noted the effect of money on the rate of interest through the saving- investment process. Hence the loanable funds theory is not a new theory.

2. Secondly, the loanable funds theory ignores certain real forces exerting influence on the rate of interest such as the marginal productivity of capital, the abstinence, and time preference.

3. In most modern economics, the rate of interest is not determined by the market forces, i.e., by the forces of demand and supply. Instead, it is determined by institutional forces, i.e., by the policies and actions of the central bank and the government. Their policies exert the most important influence on the rate of interest by determining both the demand for and supply of loanable funds-in the country.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. Indeterminate rate of interest: The rate of interest, as pointed out by Keynes, remains indeterminate in the theory as the supply of loanable funds cannot be ascertained without knowing the level of income.

5. Interest is not the reward of saving: Interest cannot be regarded as the reward for savings as savings in the form of idle cash balances do not bring any interest.

Conclusions:

Some economists claim that the loanable funds theory is better than the liquidity preference theory “because it correspondences more closely to the way in which the business world thinks of the determinants of the rate of interest and because it shows more directly the relation between the marginal efficiency of investment and the rate of interest.”

The points to be said in favour of loanable funds theory are:

1. Firstly, it appeals to common sense.

2. Secondly, it is related to money.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Thirdly, it gives due recognition to the role played by the banking system in the determination of interest.

4. Fourthly, due importance is assigned in this theory to demand and for cash balance for precautionary and speculative purposes.

5. Finally, it admits the fact that the volume of saving is positively related to the level of income.