In this essay we will discuss about the marginal productivity theory of wages.

Wages are the payments received in return for labour services and as such are the returns received by labour as a factor of production. There are various theories of wage determination. The most celebrated theory is the marginal productivity theory.

The theory is based on the following assumptions:

Assumptions:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Perfect Competition:

Conditions of perfect competition prevail in the labour market. This means that the firm can obtain all the labour it requires at the prevailing (market) wage rate. The firm is a price-taker and is faced with a horizontal labour-supply curve.

2. Homogeneity:

Labour is treated as a homogeneous factor, i.e., the productivity of each unit of labour is the same? This happens only when all workers are alike in skill, ability and efficiency.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

3. Mobility:

Labour is perfectly mobile between (among) occupations This means that forces of competition will lead to equalisation of marginal product between (among) sectors.

4. Fixity of other Factors:

All factors except labour is assumed to remain fixed. So, the change in output of the firm is attributable to change in the usage of labour input alone.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

5. Profit Maximisation:

The objective of the firm (entrepreneur) hiring labour is to maximise profits. Therefore, it’s (his) main concern will be difference between the cost of employing labour and the revenue to be gained from the sale of the output of labour.

6. The Operation of Law of Diminishing Returns:

The theory also assumes the operation of the law of diminishing marginal returns and consequent fall in the marginal product of labour with the increase in the employment of labour.

Two Concepts: MPP & MRP:

The marginal productivity theory of wages is based on two concepts, viz., marginal physical product (MPP) of labour and marginal revenue product (MRP) of labour. The MPP is the addition to the total output or product which occurs when one additional unit of labour (the variable factor) is employed. Due to the operation of the law of diminishing returns MPP initially rises but then it starts to decline. Total product increases but at a decreasing rate’.

Suppose a firm has already employed 10 workers and its total product is 30 units. Now, suppose another worker is employed, keeping all other factors fixed. As a result total product rises to 32. So, MPP is 2 units. It is the addition made to the total product by the last (here eleventh) worker.

However, a profit-maximising firm is not really interested in knowing what is the contribution of the last worker to its total product. It is more interested in knowing how much revenue can be made by selling this extra output. So, a more relevant (and important) concept is MRP.

MRP refers to the addition to total revenue received from the sale of the additional output and is calculated as the MPP, e.g., tonnes of wheat, etc., multiplied by price (which is equal to marginal revenue under perfect competition), i.e., MPP x P = MRP. Suppose, the price of the product (wheat) is Rs 100 per tonne. So, the MRP will now be Rs 200 (= 2 x Rs 100).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As under conditions of perfect competition price is constant, the MRP curve will be identical in shape to the MPP curve. (Under conditions of imperfect competition the MRP curve is obtained by multiplying the MPP by marginal revenue, i.e., MPP x MR = MRP)

A Firm’s Optimum Purchase of Labour:

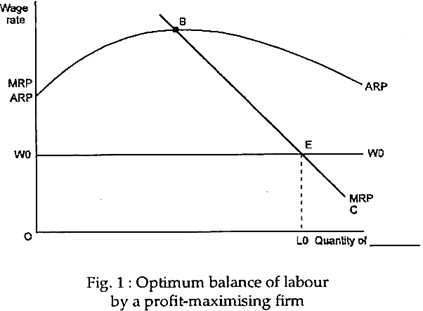

In Fig.1, the MRP curve can be seen to rise and then fall cutting the average revenue product (ARP) curve at its highest point. The ARP curve represents the average revenue, in monetary terms, per unit of labour employed. Due to perfect competition in the labour market the supply of labour will be perfectly elastic at the prevailing wage rate (W0) which is determined by the market.

A profit-maximising entrepreneur will want to employ labour as long as the MRP is greater than the wage rate (cost of labour). In Fig. 1 he will continue to employ additional labour up to OI0 as this will add more to revenue than to cost. Above OI0 additional labour will cost more than its MRP and will not therefore be employed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The profit-maximising entrepreneur will therefore employ Ol0 units of labour. If we consider the wage rate to be the marginal cost of labour, we can see that the conclusion is another form of the MR = MC rule used in the theory of the firm, point E being the equilibrium point.

A Firm’s Demand Curve for Labour:

The relevant section of the MRP curve is, however, B-C only. This is so because no firm will employ labour when the wage rate is greater than the ARP as the profit-maximising entrepreneur would never pay more to all workers than the highest ARP, as losses would result. The section of the MRP curve below ARP, i.e., B-C can be considered as the competitive firm’s demand curve for labour.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The marginal productivity theory is, therefore, a theory of how the demand for labour is determined. But, as the supply of labour is excluded, it cannot be considered as a theory of how wages are determined as it says nothing about the determination of wage rates.

Shift of the Demand Curve:

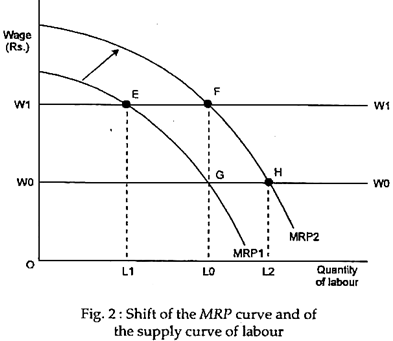

The MP theory, however, can be useful as a tool for analysing the effects on the demand for labour of the changes in the relevant variables. In Fig. 2 an increase in the wage rate from w0 to w1 will result in a reduction in the quantity employed from l0 to l1.

If, however, the MRP can be shifted upwards and outwards from MRP1 to MRP2, then the quantity of labour can remain unchanged at l0.

Alternatively, if the shift in the MRP curve takes place with the wage rate remaining constant at w0 the amount of labour employed would increase to l2 or the existing work force l0 could enjoy the higher wage rate.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Shifts in the MRP curve from MRP1 to MRP2 can be brought about by:

1. An increase in productivity brought about by the abandonment of a previously hold restrictive practice.

2. The adoption of new technology which makes labour more productive.

3. An increase in the price of the product which may be difficult given the competitive assumption.

Criticisms:

The marginal productivity theory of wages has been criticised on the following grounds:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Bias:

First, theory is one-sided because it focuses on the demand side of the labour market and completely ignores its supply side. But, in practice we observe that wages are determined by the forces of both demand and supply. So, the theory is incomplete, too.

2. Collective Bargaining:

Secondly, according to this theory wages can never be more or less than the marginal revenue product of labour. But, in practice, we observe that trade unions often demand and succeed in getting wages beyond the marginal product of labour.

Likewise, the absence of labour unions creates situations where wages are far less than the marginal revenue product of labour. In fact, wages are not always determined by market forces. Instead, wages are fixed by collective bargaining between the trade union and the employer.

3. Market Imperfection:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thirdly, the theory is based on the assumption of perfect competition in both labour and commodity markets. If we relax the assumption in any one of the markets, the major conclusion of the marginal productivity theory will not hold. Since perfect competition does not exist in most real life markets, the marginal productivity theory is unrealistic.

4. Long-Run Trends:

Fourthly, the forces of competition lead to the equalisation of the marginal product among different sectors or industries. Critics point out that the theory offers only a long-term explanation of the determination of wages. It fails to explain how wages are determined in the short run.

5. Lack of Homogeneity:

Fifthly, the theory is based on a number of unrealistic assumptions. First, the theory assumes that all workers are alike in skill, ability and efficiency, or, in other words, all units of labour are homogeneous. But, in practice, we observe that workers differ in ability efficiency and productivity. This largely accounts for inter-individual differences in wages and earnings.

6. Measurement Problem:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Critics also point out that when production is carried out on a very large scale it becomes very difficult, if not absolutely impossible, to measure the marginal product of labour. This is a practical problem. In large production units, the employment of one extra worker makes hardly any difference to the total product. Thus, we cannot arrive at an accurate estimate of the marginal product of labour.

We may note that the marginal product of labour can be measured only when a worker is actually employed in the work place. So, the question is: how to employ a worker on the basis of his anticipated marginal product? The marginal productivity theory leaves this question unanswered.

7. Economy of High Wages:

According to this theory, wages depend on the (marginal) product of labour. Critics point out that the converse is also true Labour productivity also depends on wages. It is in this context, that Alfred Marshall spoke of the economy of high wages.

According to Marshall high wages promote efficiency; low wages retard it. If the wage rate is reasonably high or fair enough, the standard of living of the workers will also be high. Consequently, the productivity of labour will rise. In this case, productivity is influenced by wages.

8. Role of Complimentary Factors:

Moreover, marginal product of labour depends not only on the number of workers employed, but also on the supply of complementary resources such as land, capital, etc. Thus, the efficiency of a worker depends, at least partly, on the amount of resources he has to work with.

If the supply of other resources is quite abundant and that of labour is scarce, the marginal product of labour will be very high indeed. The converse is also true. If a worker does not have sufficient amount of other resources, his efficiency and hence productivity are bound to be low.

9. Role of Management:

Critics also point out that the (marginal) product of labour also depends upon the efficiency or inefficiency of management. An otherwise efficient worker will not be able to deliver the goods if he has to work under an incompetent manager. (This is usually found in most public sector undertakings).

10. Non-Substitutionality of Factors:

Substitution is not always possible. It is also found that the possibility of increasing the number of labour by keeping other factors constant is very little due to technical constraints. The technical coefficients of production determine the quantities in which the units of different factors are to be combined.

11. Role of Saving:

Another criticism is that the demand for labour is not due to its productivity. The demand for labour, according to Maurice Dobb, does not depend on its marginal revenue product; instead it depends on the capitalists’ willingness to save, which depends on previous wage-bargains and on previous profits.

12. Wages not Equal to the Marginal Revenue Product of Labour:

According to Taussig, wages do not tend to be equal to the marginal product of labour for there is no specific product of labour. In his opinion, ‘wages stand for the marginal discounted product of labour’ and so wages are less than the marginal revenue product of labour.

Conclusion:

For all these defects the marginal productivity theory is not considered to be satisfactory as a determination of the wage rate in a free market. So, other theories have also been developed.

It may be stated that the marginal productivity of labour alone does not determine the rate of wages. It simply sets the maximum limit of wages; the minimum limit is set by the standard of living of the workers.

The employers invariably try to pay less than the marginal product of labour and the workers always attempt to get more than the cost of living The actual rates are determined between these two limits, depending on the relative strength of the employers and the workers’ organisations.