This article provides Hansen’s expertise guide to secular stagnation of business cycle.

Introduction:

A.H. Hansen, born 1887, is known as ‘American Keynes’. He studied fluctuations in national income suggested measures for steady growth.

His main thesis of secular stagnation was aimed at showing the inherent instability of the capitalist system. He emphasized the need of government intervention to regulate economic activities.

The essential elements in this thesis were:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) He believed that a fall in population increase will hamper economic growth. It means loss of dynamism, which in turn, means stagnation,

(b) Developed countries face the loss of the ‘Frontier Spirit, due to the limitations of resource discovery and weakening of autonomous investment caused by declining population.

Others who support Hansen’s thesis are: Jones, Arndt, Timlin, Gorbett, Barber, Mathews, Gorden, Handerson, Adler, Kurihara. They maintain that the timing and the form of most of the business cycles have been determined primarily by waves in labour supply. Amongst the most crucial factors in the economic life of a country and business is the population—people, their number, quantity and quality.

Since the Great Depression of 1929-33, a feeling has been growing in the advanced economies of the West like UK and USA that they may be faced with not only short-period cyclical unemployment but also with long-period (secular) and chronic depression. In other words, there is a tendency for the marginal efficiency of capital to decline in the secular long-run called ‘secular stagnation’.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Economic growth, by any reasonable definition, implies increasing per capita real income over time. Stagnation implies that per capita real income remains constant, declines, or grows less rapidly than it might. This is based on the fact that advanced capitalist economies, under ‘laissez faire’, are incapable of maintaining such high level of income and employment as is warranted by the technical conditions and potential resources of the economy.

“Secular stagnation refers to a mature phase of capitalist development in which net saving at full employment tends to grow, whereas net investment at full employment tends to fall. It denotes a long term trend towards a relative contraction in economic activity and an increased intensity and prolongation of short-period depressions. Although the business cycle persists, the booms are weaker and shorter and the slumps are deeper and longer.”

Thus, in the secular long run, the economy tends to become chronically depressed. The essence of secular stagnation is: “Sick recoveries which die in their infancy and depressions which feed on themselves and leave a hard and seemingly immovable core of unemployment.” Theory of secular stagnation is also known as ‘economic maturity’, ‘growing deflationary gap’, ‘increasing underemployment’ and ‘secular underemployment equilibrium’.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

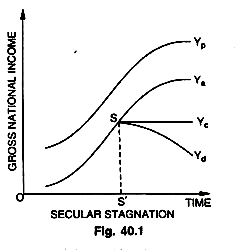

Broadly speaking, it simply means that the economy is attaining less growth in output of which it is capable: the economy may slip down, move sideways, or move forward but at too slow a rate, as in the diagram:

1. In this diagram, the curve Yp shows the potential gross national real income that the economy is capable of attaining.

2. The curve Ya shows the actual gross national real income: the secular stagnation begins at S’ time, from S’ onwards the gap widens between the trend and path of potential income and trend and path of actual income.

3. When actual income curve (Ya) reaches S at S’ time, the secular stagnation sets in, because the income may move forward at too slow a rate (SYa) or may move sideways (SYe) or it may move downwards (SYd).

Secular Underemployment Equilibrium:

The theoretical possibility of secular underemployment equilibrium (secular stagnation) arises from two facts:

(i) The investment (propensity to invest) is not high enough as to offset savings at full employment;

(ii) The propensity to consume (save) remains more or less stable.

As such, the economy is, no doubt, in equilibrium (but at underemployment equilibrium) and remains there for an indefinite period. This tendency of the economy to remain at underemployment equilibrium in the long-run is called secular underemployment equilibrium (secular stagnation).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

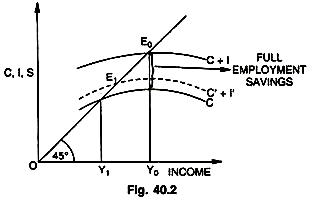

The idea is shown in the diagram:

1. In this diagram, we measure C, I and S along vertical axis and income along horizontal axis.

2. Starting with the position of full employment equilibrium, at E0, we find that investment schedule (C + I) which is drawn above the consumption schedule (C) is high enough to offset full employment savings at the Y0 level of income. In other words, the economy is able to invest at the same rate at which it is disposed to save out of full employment income.

3. Now suppose the investment opportunities decline on account of various reasons. This will lead to lowering investment schedule shown by the dotted curve C’ + I’ which is just above the C curve and intersects the 45° line (at E1) to give the new OY1 level of income, which is sufficiently below the full employment level of income OY0. The fall in income from OY0 to OY1 causes loss of a large number of jobs (employment).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

4. It is obvious, therefore, that in order to maintain full employment equilibrium, either investment must be kept high enough as to offset the amount of full employment savings or saving must fall in order to raise the consumption to a level high enough as to reduce saving to be offset by investment. Failing which, the economy will be faced with the inevitable destiny of chronic mass unemployment called secular stagnation.

It is, thus, clear that important characteristic of the marginal efficiency of capital is its tendency to fall in the secular long-run. It is just a new name for the old idea of the falling rate of profit. Many great economists like Adam Smith, Karl Marx, David Ricardo, John Stuart Mill, Schumpeter, Domar and Harrod have given arguments and accepted the tendency for the falling rate of profit as one of the basic features of long-term development of the capitalistic economy.

Domar appears pessimistic about the prospects of maintaining full employment; he leaves investment to be determined independently, but he implies that it is more likely to be inadequate than excessive, so that future prospects are of underemployment rather than of perpetual inflation.

This view of Domar tallies with the view expressed by A.H. Hansen in the 1930s, which later on became popular under ‘secular stagnation thesis’, that the performance of the economy in the long-run would fall further and further below its capacity, so that unemployment would tend to grow over the years. They all agree that the capitalist economy, in the course of its development, may eventually reach a position of excess of savings over investment, causing chronic underemployment and economic stagnation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to classical economists every economy must reach a stationary state in which growth ceases. Marx and Schumpeter predict an ultimate downfall of the capitalist system. Harrod and Domar show how it becomes more and more difficult to maintain full employment in a growing economy. Hansen feels that in advanced economies, in the absence of state intervention, at the full employment level, net savings tend to exceed net investment resulting in secular stagnation.

These writers, however, widely disagree as regards the reasons which cause secular stagnation. Keynes explains the secular decline in the marginal efficiency of capital by a fall in prospective yield on account of the abundance of capital assets, as the process of capital formation goes ahead with increasing force.

Keynes on Secular Stagnation:

“Keynes was not always a stagnations: and in fact he never developed his theory of stagnation systematically as has been done so ably by Prof. Hansen. Keynes presented his most systematic exposition of a stagnation theory in a paper in 1939. Here Keynes was quite specific on the effects of a declining population (on investment), on the need of combating stagnation by reducing interest rates and raising consumption through institutional measure.”

There is no better statement of stagnation thesis than that given by Keynes himself. “The richer the community, the wider will tend to be the gap between its actual and its potential production and, therefore, the more obvious and outrageous, the defects of the economic system. Not only is the marginal propensity to consume weaker in a wealthy community but, owing to its accumulation of capital being already larger, the opportunities for further investment are less attractive”.

During the 19th century, the growth of population and of investment, the opening up of new lands, the state of confidence and the frequency of war over the average (say) each decade, seem to have been sufficient, taken in conjunction with the propensity to consume to establish a schedule of the marginal efficiency of capital which allowed a reasonable satisfactory average level of employment to be compatible with a rate of interest high enough to be psychologically acceptable to wealth owners. Today and presumably for the future the schedule of MEC is for a variety of reasons, much lower than it was in the 19th century.

Reasons:

Different reasons have been given by different writers from time to time as to the causes of secular stagnation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

1. Reasons that lay stress on exogenous (outside the system) factors like technology, population growth, development of new territories, expansion of markets.

2. Reasons that lay stress on endogenous (internal) factors like the concentration of industry and the development of monopolistic competition.

3. Reasons concerning the fundamental changes in social institutions like increasing state control of business and development of labour unions.

There are, however, two important ways to analyze the theoretical possibility of secular stagnation:

(i) The tendency of savings to exceed investment

(ii) Declining investment opportunities.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The factors which cause excess of saving over investment in the long run are:

(a) Paradox of Thrift:

Secular underemployment arises from certain historical tendencies peculiar to the advanced capitalist economies. Such economies, during the course of their development, reach a position in which, for psychological, technological, institutional and other reasons they find themselves faced with an excess of saving over investment. Secular stagnation, thus, originates in the constant tendency of saving to exceed investment.

The belief that saving is a great individual virtue has been belied. It is now regarded as a great social vice. The primary evil of thrift lies in the fact that in conditions of full employment it produces more saving than can be offset by investment to maintain the full employment level of income.

There would be no cause for alarm (secular stagnation) in advanced capitalist economies (which are characterised by high propensity to save) if investment was equally high at all times; but that is not the case in actual practice. Savings are not automatically offset unless investment opportunities also expand simultaneously. This constitutes the famous ‘paradox of thrift’ and hence fear of stagnation.

The 19th century was a period of unparalleled economic development caused by dynamic growth factors like population, new inventions, new markets, new area, wars, etc. Under those circumstances, “to save and to invest became at once the duty and the delight of a large class, and the morals, the politics, the literature, and the religion of the age joined in a grand conspiracy for the promotion of saving.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

“There was then a tendency for investment to outrun saving—so much so that economists took the scarcity of capital for granted. Beginning with the turn of the century, the rate of investment in the advanced countries began to slow down, yet mentality lagged behind reality; economists let alone laymen, were still inclined to the notion that unlimited investment opportunities were ahead.” Therein lay the error and hence the cause of stagnation.

(b) Unequal Distribution of Income:

Unequal distribution of income is another important factor causing secular over saving. Advanced capitalist economies are characterized by high propensity to save (on account of richer population). The gap between the marginal propensity to save of lower income groups and that of higher income groups causes greater amount of savings in the richer income groups.

Thus, saving are greater when income distribution is unequal than when it is equal. Let us illustrate it with a simple example. Suppose there are two income groups and they together receive a total income of Rs. 10,000 annually. Suppose each group receives Rs. 5,000 and both income groups have the same propensity to save of 0.2 (20 per cent). Thus, each group will save Rs. 1,000 making a total saving of Rs. 2,000 in the economy. Suppose further that one group receives Rs. 9,000 and another group receives Rs. 1,000.

The group with higher income (Rs. 9,000) will have a higher propensity to save, say 0.4 (40 per cent) i. e., it will save Rs. 3,600 out of Rs. 9,000, whereas the other group will not be able to save anything, as its income has fallen (from Rs. 5,000 to Rs. 1,000), therefore, its propensity to save has also fallen (from 0.2 to 0). In spite of this, the total savings in the economy are more by Rs. 1,600 (Rs. 3,600 – Rs. 2,000).

This shows that savings increase more with an unequal distribution of income (being Rs, 3,600) than when the distribution of income is equal (being Rs. 2,000). The greater the inequalities, the higher would be the propensity to save. Though conceptual and statistical difficulties in the measurement of the degree of inequality of income—distribution bar a precise identification of the secular tendency in this regard, a few broad conclusions could be easily formulated; e.g., large and probably increasing, inequalities in the distribution of personal income before tax appear to be inherent in the private—enterprise system.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(c) Institutional Savings:

Another factor which has let to the (permanent) over saving gap is the growth of joint stock and corporate form of business organisations. During prosperous years a large part of corporate profits is kept as undistributed profit which constitutes a major part of total savings. Corporate saving consists of depreciation reserves for replacement and is reflected in the amount of undistributed profits of corporations. The rising secular tendency in the ratio of corporate undistributed profits to national income, at full employment appears mainly on account of two factors.

The first is the rise in the ratio of corporate profits before tax to national income, because of the growing predominance of corporate enterprise. The second is the rise in the ratio of corporate undistributed profits to total corporate profits after tax, owing to the desire of those who run corporations to expand their businesses. Besides, the growth of life insurance and other institutions has also given a fillip to the tendency to over save relative to available investment opportunities, thereby enhancing the chances of secular stagnation.

The factors which lead to the declining investment opportunities in the long-run are as follows:

(i) Population:

When it is recalled that population growth accounted for almost half the total demand for new capital in the 19th century, the economic importance of a declining population is not difficult to understand. In the 19th century the population grew at a very high speed. According to Hansen, 60 per cent of capital formation in USA and about 40 per cent in the Western Europe during the 19th century was due to rise in population. Large amounts of goods and services were needed to meet the requirements of the growing population necessitating huge amounts of investments.

It led to an expansion of new towns and cities, increased activity in the fields of construction, public utilities, transport and communication facilities. Keynes also believed that population growth stimulates investment.

He, however, felt that a mere increase in numbers is not what is important, but rather an increase in the purchasing power; an increase in the number of beggars does not in any way lead to the expansion of markets. Thus, population growth was responsible to a large extent for the capital formulation in the 19th century. The dawn of the 20th century saw a rapid decline in the population growth in the important countries of the West, like, England, France the United States, etc.

With the slowing down of the population growth, capital accumulation also suffers in the sense that capital becomes abundant relative to labour and the marginal productivity of capital falls. Thus, declining rates of population growth have resulted in the decline of investment opportunities causing secular stagnation.

According to Hansen, the main cause of slump is tapering off population growth, slow down in resources discovery and technological change. Under these conditions autonomous investment falls and if the government investment does not compensate, induced investment also falls, engulfing the economy in slump. Fall in autonomous investment is a secular affair in Hansen’s thesis while a fall in induced investment is a cyclical affair.

(ii) New Territories and Markets:

What holds true of population growth also holds good for expansion of new territories and development of markets. In fact, it may not be wrong to say that population growth, development of markets, and expansion of territories have gone hand in hand. The expansion of territories and markets as a result of population growth requires huge investments in various types of economic activities like railways, roads, highways, communication facilities, canals, dams, bridges, etc.

Further, when new territories are developed to settle the growing population and natural resources are exploited, huge investments are needed. The removal of these factors narrows investment opportunities. The era of territorial expansion, like the era of population growth, has to come to an end for advanced capitalist countries of the west. Therefore, the dangers of secular stagnation have become more real.

(iii) Existing Stock of Capital:

Keynes considers the extent of the existing stock of capital as one of the crucial factors causing a tendency towards secular stagnation. The growth of capital leads to a fall in the marginal efficiency of capital. This fall in the MEC is due to the fact that every addition to capital equipment comes in competition with the existing stock of capital thereby lowering the prospective yields on new investments and rendering them less attractive.

(iv) Uncertain Nature of Technology:

Secular tendency of underemployment equilibrium is also caused by the uncertain nature of the techniques of production and development. In the 19th century, on account of the population growth development of markets and territorial expansion, huge technological developments, both of ‘capital deepening’ and ‘capital widening’ nature took place. The transformation from a primitive handicraft economy to ‘advanced roundabout’ capitalist economy required huge capital.

But with the turn of the century, the developments in the techniques of production have been on capital saving lines rendering the demand for new capital quite inadequate. In many cases, for example, such plant and machinery have been installed as to increase productivity merely by speeding up the operation of existing plant and machinery thus creating the fear of secular stagnation.

(v) Institutional Development:

A few institutional developments in the present century made the fear of secular stagnation more real. They have slowed down the opportunities of new investments in technical invention and retarded innovation. For example, trade unions opposed the use of technical discoveries fearing technical unemployment. The growth of trade associations and monopoly had similar effects. This narrowed investment opportunities, made replacements less necessary and even failed to raise the propensity to consume.

As such, apart from the possibility of ‘technical progress’ in the field of defence, space research, etc. new wants and processes are not likely to give a fillip to additional investment as strongly as was the case in the 19th century. On the other hand, increasing dominance of monopoly and oligopoly has bad unfavourable effects on investment in many ways, because the output is not expanded to the level where price equals the marginal cost. Restrictions of output in the monopolised and oligopolised sectors diminishes the scope for further investment in such sectors. Under such circumstances introduction of innovations are delayed. Thus, on account of the growing imperfect competitive market structure inducement to invest is bound to be weakened.

(vi) Capital Saving Techniques:

In recent times technological inventions are biased towards capital saving techniques. The latest trend towards air-conditioning, refrigeration, television shows how capital goods are required at less capital outlay. To quote Samuelsen, “Thus, the invention of airliner may make possible the development of Siberia without billions and billions dollars of investment in public roads and rail roads………… Atomic energy may minimise the need in many parts of the world for costly hydro-electric reclamation projects………… Science gives and takes as far as investment is concerned, and Hansen thinks these may continue to be—what he believes to have been true of the 1930s—preponderance of capital—saving invention.”

Besides, development of safeguards against frequent breakdowns and quick wear and tear has considerably reduced the replacement demand incident to rapid depreciation. Moreover, equipment now-a-days is often installed which increases productivity by merely speeding up the operation of the existing plant and equipment. All such capital saving innovations have gone to affect the growth of investment demand in recent years especially in advanced economies increasing the possibilities of secular stagnation.

(vii) Weak Exports Stimulus:

It is no doubt true that expanding exports act as a great stimulus to investment in the export industries. This stimulus to capitalist development is the strongest when exports increase at a fast pace and are accompanied by a growing export surplus and when the consequent expansion of imports not only does not impair potential investment but also brings about a rapid decline of the pre-capitalist sector. Conditions are not at all favourable in these respects as they were a century ago on account of changed pattern structure of foreign trade today.

Further, net private saving corresponding to full employment may also be offset by positive net investment abroad. It was so in the pre-World War I period. But the current political climate and other factors leave hardly any scope for revival of capital movements from advanced to underdeveloped countries, strengthening the fear of secular stagnation.

Secular Stagnation in Underdeveloped Economies:

Doubts, however, have been expressed as to the accuracy of the secular stagnation thesis both as regards to its form and contents. Secular stagnation thesis has been dismissed as ‘a bogey’ by some, and discounted as an ‘overstatement’ by others. A few call it ‘an over exaggeration’ of facts. It is argued that these dynamic growth factors like population, territorial expansion etc. might have slowed down in advanced capitalist economies of the west.

In underdeveloped economies like Bangladesh, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, where transformation from primitive handicraft, rural and non-monetised economy to monetised, roundabout developed economy is not yet complete and even the ‘take-off stage in the real and proper sense has not been attained, the fear of secular stagnation is a far cry. There is neither a tendency to over-save nor a tendency to under invest.

Terborgh regards the stagnation thesis a child of the pessimistic depression period and remarks that just as one swallow does not make a summer, so one depression, even a great one, cannot establish a presumption towards stagnation. Terborgh questions the vital importance of a few great innovations as compared with ‘many small ones’. “There is no real evidence that one ‘great new industry’ is more dynamic in its impact on capital formation than ten small new industries.

The important thing is the total flow of technological development, not its degree of concentration. Given an abundance of rising industries like aviation, mechanical, refrigeration, air-conditioning, radio, television, rayon, plastics, quick freezing prefabricated housing, light metals, powered metals, ocative gosoline, gas turbine, jet propulsion, spun glass, cotton pickers, combined harvestors, electronics to name only a few at random—the total volume of direct and induced investment can be tremendous There is………. no evidence of our increasing proportion of capital saving innovation.” Therefore, the concept of secular stagnation is said to be peculiar to advanced economies only.

Critical Evaluation:

Neisser, Terborgh, Fellner, Hoover, Spengler, Haberler Peterson, Robinson, Duesenberry, Ellis, Willams, Angell, Lerner, Bronfenbrenner, etc., have severely criticised Hansen’s approach and thesis of secular stagnation. They maintain that growing population is not at all necessary for growing demand function. The fears of economic maturity and stagnation have been exaggerated. In a dynamic system there is always spontaneous changes in tastes of consumers which necessitate capital using techniques.

Terborgh feels that given the abundance and concentration of modern industries in advanced countries, like aviation, refrigeration, air-conditioning, radio, television, rayon, plastics, quick-freezing, prefabricated housing, light-metals, gas turbines, jet propulsion, electronics, engineering—light and heavy, combined harvesters, nuclear and atomic energy, space discoveries—to mention only a few—the total volume of direct and induced investment is bound to be tremendous even in developed economies. There is, therefore, neither any fear nor any evidence of secular stagnation as propagated by Hansen.

As such in advanced economies also its validity has been doubted by some economists.’ They feel that the decline in dynamic growth factors is only a temporary phenomenon and considerable investment opportunities still continue to exist in advanced economies. They believe that there are bound to be immense and spontaneous changes in wants, fashions, tastes of consumers and techniques of production that growth and development bring in their wake.

Insofar as millionaires get satisfaction in constructing splendid mansions to contain their bodies when alive and pyramids to shelter them after death or repenting for their sins erect temples: the day where the abundance of capital will interfere with abundance of output may be postponed. Inflationary conditions in the post-war world made the idea of ‘secular stagnation’ seem obsolete and suggested the possibility ‘secular exhilaration instead, in which the aggregate demand would be constantly running ahead of full employment output.

They further feel that the danger to secular stagnation can be eliminated by the new investment opportunities afforded by the new era of development in the backward regions of Asia and Latin America, which are pledged to improve the lot of the masses by removing poverty and ignorance.

Thus, the investment policies in advanced economies, savings, avoiding the danger of secular stagnation. Moreover, secular stagnation is based on the thesis that propensity to consume is stable in the short- run whereas in the secular long-run it shows a tendency to rise. What is, therefore, needed is a proper co-ordination of national and international measures for development.

The critics of secular stagnation feel that, in reality, there is the danger of ‘secular inflation’ rather than the danger of ‘secular stagnation in advanced economies.’ Prof. Martin Bronfenbrenner asserts that it is not secular stagnation but secular inflation which threatens the advanced capitalist countries of the west. He says, “We look on secular inflation, not as strictly inevitable but as likely to dominate the economic life in capitalist countries for the next few years………. the world of secular stagnation is the world of sound finance and of the Gold standard. It is not currently in existence.

It passed into coma in 1933, when Roosevelt and Hitler came to power, and died completely on the several battle fronts of World War II. Its importance today may be largely academic, the world of secular inflation, however, is the pressure economy of the present including the political necessity of maintaining high employment at whatever cost”.

Inflationary conditions in the post-war world made the idea of secular stagnation seem obsolete, and suggested a prognosis of ‘secular exhilaration’ instead, in which aggregate demand would be constantly running ahead of full-employment output. That is why the modern theory of stagnation is gentler and less pessimistic than Hansen’s. The experience of the United States economy during the late 1960s and the early 1970s when successive recessions, though relatively mild, seemed to carry the economy further below its capacity, has caused the ‘secular inflation’ or ‘exhilaration’ thesis to appear somewhat obsolete too. How far these predictions regarding the fallacy of secular stagnation (or the possibility of secular inflation) are real, valid or true, only time will tell. It, however, involves “a great guessing game”.

It may, however, be realised that the advocates of secular stagnation never meant that the investment opportunities would completely vanish in advanced economies. What they simply emphasized was that as compared to the 19th century, 20th century affords less opportunities for investment on account of the basic changes in the dynamic growth factors like population, technological changes, etc.

The main position of the stagnationists is that there is nothing inherent in the economic system of the rich countries to ensure a rate of net investment necessary to provide full employment, which is a function of the change and growth in the economic system. The stagnation thesis contains the denial that the mere process of consumption is sufficient to ensure net investment to promote full employment in the long run.

How to Avoid Secular Stagnation?

The effect of the disappearance of the dynamic growth factors has been to lower the marginal efficiency of capital. The constant tendency of saving, to outrun investment at full employment in the long run (secular stagnation) can be avoided, if the rate of interest also falls sufficiently to offset the fall in the marginal efficiency of capital failing which investment is bound to decline and with it national income.

The rate of interest, no doubt, can fall but Keynes denied the possibility of the rate of interest, falling so low as to offset the fall in the MEC. In other words, where the MEC can fall to zero, rate of interest cannot. Hence, as long as the MEC falls at a faster rate than the rate of interest, the danger to the tendency of secular stagnation is not easy to avoid. Therefore, the suggestion that the rate of interest may be lowered to avoid it does not carry much weight. Vital measures to counteract secular stagnation will include steps to discourage savings and stimulate investment.