This article provides Keynes’s expertise guide to inflation and inflationary process.

Meaning of Inflation:

It is not easy to give a precise and yet generally acceptable definition of inflation.

Different monetary experts define it in different ways. Indeed it is debatable whether inflation is a single definitive phenomenon which is capable of being precisely described.

Professor Crowther says, “inflation is a state in which the value of money is falling, i.e., prices are rising.” Pigou holds the view that “inflation exists when money income is expanding more than in proportion to income earning activity.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Gregory associates inflation with a state of abnormal increase in the quantity of money, and Hawtrey with ‘the issue of too much currency’. Inflation, thus, is a monetary phenomenon characterized by high prices (falling values of money). Kemmerer expressed the view that inflation would exist in an economy when the amount of money exceeds the value of goods and services. Coulborn says it is a phenomenon where “too much money chases too few goods.”

Ackley, Johnson and Friedman define inflation in terms of a process of rising prices. Friedman thinks of inflation as a process of “a steady and sustained rise in prices.” Ackley defines “inflation as a persistent and appreciable rise in the general level or average of prices”. Emile James has also given expression to a similar opinion that “inflation is a self-perpetuating and irreversible upward movement of prices, caused by an excess of demand over capacity to supply.”

However, any rise in price level should not be taken to mean inflation. No doubt, price rise is an important feature of inflation, but it does not mean and always reflect inflation, as prices in a dynamic economy do rise on account of other factors also. Inflation may sometimes occur without a rise in prices; for example, when on account of the increase in productivity, cost of production may fall when prices are kept stable. Prof. Paul Einzig, therefore, likes to define inflation as “a state of disequilibrium in which an expansion of purchasing power tends to cause, or is the effect of an increase of the price level.”

Keynes Views on Inflation and Inflationary Process:

According to Keynes, inflation is caused by an excess of effective demand. To him, the state of true inflation begins only after the level of full employment has been attained. Suggesting that inflation in the ordinary sense was no longer the heinous affair that the conservative mood made it out to be, he insisted that a secular rise in prices could be a pleasant and respectable experience. It was this attitude that led some persons to call him a ‘congenital inflationist’. He says, “So long as there is unemployment, employment will change in the same proportion as the quantity of money, and when there is full employment, prices will change in the same proportion as the quantity of money.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

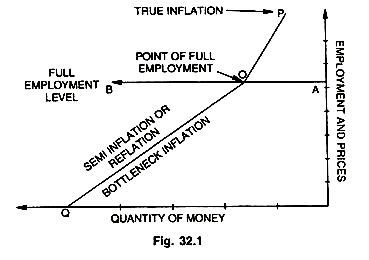

According to him, we need not unduly fear inflation because as long as there are unemployed human and material resources, an increase in the quantity of money will go to increase employment. After full employment all increase in money increase the price level. Keynes does not deny that prices may rise even before full employment but such a phenomenon he called ‘semi-inflation’ or reflation, or ‘bottleneck inflation’. He has defined full employment as the point at which or beyond which true inflation sets in as shown in the Figure 32.1.

In this Figure AB shows the level of full employment or the point of full employment. Although the prices start rising even before the full employment is reached at O, this is not called true inflation, but ‘semi-inflation’ or ‘reflation’ or ‘bottleneck inflation’.

Till the level of full employment is reached, increases in the quantity of money lead to increases in employment and only, after the level full employment has been attained, increases in quantity of money result in true inflation as shown by OP. However, Milton Friedman stresses that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. Similarly, F.W. Paish thinks of inflation as an essentially a monetary phenomenon. He related the phenomenon of inflation to a rise in money incomes rather than in prices.

Inflationary Gap:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Keynes has tried to analyze the phenomenon of inflation in terms of inflationary gap. The inflationary gap shows a situation in the economy when anticipated expenditures (demand) exceed the available output (supply) at base prices or at the pre-inflation prices. The Chancellor of the Exchequer (England) defined the gap as “the amount of the government’s expenditure against which there is no corresponding release of real resources of the manpower or material by some other member of the community.”

Thus, the inflationary gap is measured by the difference between the disposable income on the one hand and the output available for consumption on the other. The concept of inflationary gap was developed by Keynes in his pamphlet ‘How to Pay for the War’ by functionally relating expected expenditures to disposable income in relation to the value of available output at base prices (or constant prices). In other words, when on account of increased investment expenditure or government expenditure or both, money income rises, but due to limitations of the capacity to produce real income, the supply of goods and services does not increase in the same proportion, an inflationary gap comes to exist giving a fillip to rise in prices.

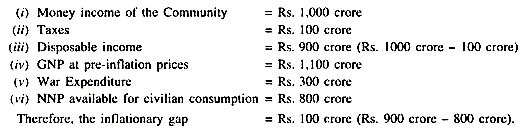

The prices continue to rise so long as the gap exist. So long as goods are available in plenty at the base price, no inflationary gap will exist; it arises only when the total money income that people are keen to spend on consumption exceeds the total output available at pre-inflation prices. Keynes, however, argues that a division of the economy into commodity market and factor markets essential because the forces which determine the inflationary gap in the commodity markets are quite different from the factors that determine the inflationary gap in the markets for factor prices. How an inflationary gap will arise in a war economy is shown in the table and given in the Fig. 32.2.

In the Fig. 32.2, C + I curve intersects C = Y line at the equilibrium point E0, which gives us equilibrium income Y0. We assume OY0 income to be full employment income. An increase in investment expenditure by consumers, business houses and government will shift the C + I curve to C + I curve, giving us a higher money income OY1. Vertical distance E1G measures the inflationary gap.

It is the difference between what the economy would spend (anticipated expenditure = E1Y1) and what it has available in terms of real goods and services (E0Y0). The difference is (E1G), the inflationary gap which will merely raise the prices. Inflationary gap has to be wiped out by reducing the excess purchasing power with the help of appropriate tax measures, or voluntary or compulsory saving by the people.

It may be noted that inflationary phenomenon is highly dynamic and the analysis given above, being static in nature, has its own limitations. Firstly, there are always important time-lags between the receipt and expenditure of income, and between the adjustment of wages and prices. But for these time-lags, inflation during and after the war would have been much more serious.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Keynes in his How to Pay for the War wrote, “It is these time-lags and other impediments that come to our rescue. Wars do not last forever”. The larger the spending lags and the wage-adjustment lags, the lower is the impact of inflation. Secondly, the gap analysis is related entirely to the flow-concepts. This is to say, it deals with current flows of income, war spending’s, consumption and savings.

The rise in price and the expectations of a further rise, in practice, will not be confined to prices of current output alone, but will also affect the prices of the stock of output which had been previously produced and is still available in the market. Moreover, the disposable income which represents income currently paid out minus taxes, may include idle balances to aggravate inflation.

Thus, the salient features of inflation are that inflation is always accompanied by a rise in prices. Inflation is essentially an economic phenomenon as it originates within the economic system and is fed by the action and interaction of economic forces. Inflation is a dynamic process. However, a cyclical movement is not inflation. Inflation is a monetary phenomenon. The inflationary process may be cost-push or demand-pull.

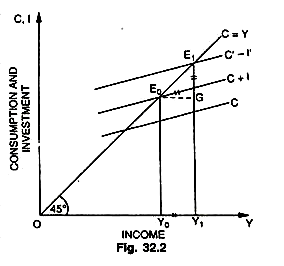

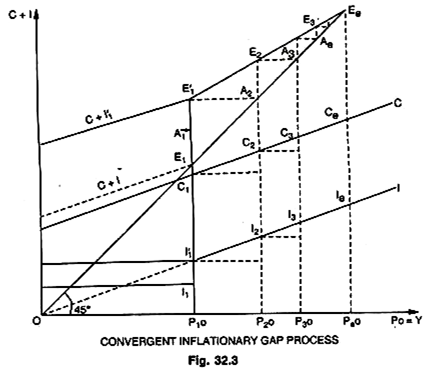

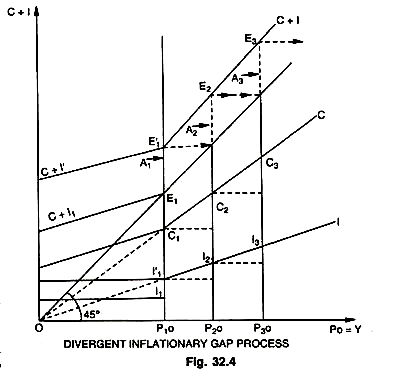

The Fig. 32.3 shows the dynamic equilibrium process of inflation through convergent and dynamic disequilibrium process through divergent inflationary gaps. A step by step analysis of these two cases—a convergent inflationary process, which terminates in new equilibrium and a divergent inflationary process, which involves continuous disequilibrium—will help clarify the essentials of the process of demand inflation.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In Fig. 32.3 there is initial full employment equilibrium at E1; at any point Po is equal to Y (price X output). There is inflationary gap at A1 —which results from an increase in autonomous .investment from I1 to I1 and the sum of consumption and investment expenditures at E1 now exceeding the C and I expenditures at E1, the value of full employment output at pre-existing prices.

Initially an increase in investment expenditures will raise income by a like amount, from P1o to P2o. This rise in income is entirely due to higher prices and the rise in P is proportional to the rise in expenditures.

Due to increase in P an increase in I do not produce for business the desired amount of goods. But business is determined to acquire per period the planned amount of goods and stands ready to raise investment expenditures as required to meet this goal—investment expenditures depending on price level P.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At price level P1, expenditures of I1 would be required but because P rises after income has exceeded P1o a kink appears in the investment curve at P1o with income new at P20, the investment curve shows that I will rise from I1 to which again produces an inflationary gap A2.

At P20, the inflationary gap is A2—a gap smaller than A1. This new gap raises money income to P30, at which, by the same reasoning, another but smaller inflationary gap appears at A2 and so on. Thus, at each step, business comes close to securing the amount of goods desired and so finds it essential to increase investment expenditures by ever smaller amounts.

In this way, the inflationary gap is eventually closed when income has risen to Peo designating an equilibrium price level. It will stabilize at Pe, and income level at Peo provided there are no further disturbances. This income level shows new equilibrium because investment expenditures of Ie secure for business the amount of goods it desires. Once this is achieved, there is no further rise in, ‘I, no further rise in level of Y and no further rise in induced consumption expenditure. It must be seen in this process which converges towards new equilibrium at Ee—that is finally attained only because for one or more reasons real consumption expenditures fall below these at Peo, even though the c + 1, economy’s real income remains unchanged as inflation carries money income upto P2o, P3o and beyond.

Figure 32.4 shows that consumers may try to maintain the real consumption they enjoyed at the full employment income of P1o as inflation carries money income to P2oand above. A rise from I1 to I1 introduces the inflationary gap A1 and sets an inflationary process into motion. Consumers now adjust money consumption expenditures upward with rising prices in an attempt to maintain the same real consumption as enjoyed at P1o. This results in a kink in the consumption function at P1o. When income rises from P1o to P2o, the increase in consumption expenditures from C1 to C2 and increase in investment expenditures from I1 to I2 add up to the inflationary gap shown by A2—a gap larger than A1.

This gap pushes the income upto P3o and so on, at which level, by the same reasoning still greater gap A3 results. This widening of the gap shows that inflation will proceed without limit. This gap will continue to widen as long as the combined real demands of consumers and business for output exceed the flow of output at the full employment level. The process has been shown for a two sector economy and if the government sector were to be included—it will make no difference to the analysis. A rise in the combined expenditures of the three sectors—whether it results, as before, from a rise in investment expenditures or from a rise in autonomous consumption or government expenditures—would create an inflationary gap at P1o and force a rise in P.

Inflationary Pressures:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

A full theoretical analysis of the causes of inflation is difficult because there is no single theoretical definition: there are varieties of inflation, each with a distinct theoretical explanation. Inflationary pressures arise both from the demand side and the supply side. Demand means the demand of money-income for goods and supply means available output on which money-income can be spent.

On the demand side, the major factors which cause inflationary pressures are the supply of money, disposable income, business expenditures and foreign demand. During war and post-war periods bank credit expanded to an enormous extent and became at once a cause and effect to inflationary pressure.

Further, during inflation, disposable incomes are likely to remain at high levels mostly on account of high levels of national income. Similarly, expenditures on account of business opportunities also expand owing to its speculative character in an inflationary boom. Further, increased monetary demand is also due to foreign expenditures on domestic goods and services.

As against, this type of sharp rise in the monetary demand (demand for money), the supply of goods and services does increase but slowly, the basic limiting factor being the level of full employment itself, resulting in shortage of labour, raw materials and equipment. The supply position is further aggravated by the wage-price spiral.

According to Prof. K.K. Kurihara, “these and many other dynamic influences coming as they do from both the demand side and supply side, lead to speculative business and consumer spending and add to the existing inflationary pressures.”

According to Dernburg and McDougall, “An economy that tries to grow more rapidly than the required rate of growth will suffer from inflation. Inflation may come about because the government attempts to absorb more resources than are released by the private economy at the existing price level. It may come about because various groups in the economy attempt to improve their relative income shares more rapidly than the growth of their productivity. It may come about because buoyant expectations cause the demand for goods and services to rise more rapidly than it is possible for the economy to expand output. And it may come about from interactions between some or all of the above factors.”