Inflation in India: Causes, Effects and Curve!

Meaning of Inflation:

By inflation we mean a general rise in prices. To be more correct, inflation is a persistent rise in the general price level rather than a once-for-all rise in it.

On the other hand, deflation represents persistently falling prices. Inflation or persistently rising prices is a major problem in India today. When price level rises due to inflation the value of money falls. When there is a persistent rise in price level, the people need more and more money to buy goods and services.

To enable the people to meet their daily needs of consumption of goods and services when their prices are rising, their incomes must rise if they have to maintain their standard of living. For government employees, their dearness allowance is increased. Wages and salaries employed in the organised private sector are also raised, though after some time- lag.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

But people with fixed incomes and those who are self-employed are unable to raise their prices and suffer a lot due to inflation. The poor suffer the most from persistent rise in prices, especially of food-grains and other essential items.

Rate of inflation during the seventies and eighties was very high as compared to the rates of inflation experienced earlier during previous periods. In India, in recent years, 2010-11, 2011-12 and 2012-13, rate of inflation as measured by consumer price index (CPI) has been in double digit figures. Prior to Jan. 2013, even WPI inflation was quite high which compelled Reserve Bank of India to adopt tight monetary policy.

Causes of Inflation:

Let us understand how the inflation originates or what causes it.

Depending upon the specific causes, three types of inflation have been distinguished:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(1) Demand-pull inflation,

(2) Cost-push inflation, and

(3) Structuralist inflation.

An important cause of demand-pull inflation is the excessive growth of money supply in the economy. We will explain this cause of inflation in the Monetarist Theory of Inflation. We will explain and discuss below these three types of inflation.

Demand-Pull Inflation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This represents a situation where the basic factor at work is the increase in aggregate demand for output either from the households or the entrepreneurs or government organised. The result is that the pressure of demand is such that it cannot be met by the currently available supply of output.

If, for example, in a situation of full employment, the government expenditure or private investment goes up, this is bound to generate an inflationary pressure in the economy. Keynes explained that inflation arises when there occurs an inflationary gap in the economy which comes to exist when aggregate demand for goods and services exceeds aggregate supply at full-employment level of output.

Basically, inflation is caused by a situation whereby the pressure of aggregate demand for goods and services exceeds the available supply of output (both being counted at the prices ruling at the beginning of a period). In such a situation, the rise in price level is the natural consequence.

Now, this imbalance between aggregate demand and supply may be the result of more than one force at work. As we know, aggregate demand is the sum of consumers’ spending on consumer goods and services, government spending on goods and services and net investment being contemplated by the entrepreneurs.

When aggregate demand for all purposes—consumption, investment and government, expenditure—exceeds the supply of goods at current prices, there is arise in price level. Since inflation is a continuous increase in the price level, not a one time rise in it, sustained inflation requires continuous increase in aggregate demand.

In the modem macroeconomics, inflation is explained with AD-AS model. Inflation can be explained by increase in aggregate demand (called “demand shock”) or decrease in aggregate supply or rise in cost of production generally called “supply shock”. Demand-pull inflation occurs when there is upward shift in aggregate demand when supply shocks are absent.

As stated above, demand-pull inflation occurs when there is increase in any component of aggregate demand, namely, consumption demand by households, investment by business firms, increase in government expenditure unmatched by increase in taxes (that is, deficit spending by the government financed by either creation of new money by the central bank or borrowing by the government from the market).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To illustrate the cause of demand-pull inflation, let us assume the government adopts expansionary fiscal policy under which it increases its expenditure without levying extra taxes to finance its increased expenditure by borrowing from the Reserve Bank of India.

To illustrate the above point, let us assume that the government adopts expansionary fiscal policy under which it increases its expenditure on education, health, defence and finances this extra expenditure by borrowing from Reserve Bank of India which prints new notes for this purpose. This will lead to increase in aggregate demand (C + I + G).

If aggregate supply of output does not increase or increases by a relatively less amount in the short run, this will cause demand-supply imbalances which will lead to demand-pull inflation in the economy, that is, general rise in price level.

Similarly, an inflationary process will be initiated if business firms anticipating the opportunities of making profits decide to invest more and to finance the new investment projects by borrowing from the banks being unable to get sufficient funds through savings out of profits and savings invested by the public in them.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This new investment by the firms leads to the increase in aggregate demand for goods and services. However, inflation will occur by this new investment if aggregate supply of output does not increase adequately in the short run to match the increase in aggregate demand.

Therefore, demand-pull inflation generally occurs when the economy is already working at full-employment level of resources or what is now generally called when there is natural rate of unemployment. This is because if aggregate demand increases beyond the full-employment level of output, output of goods cannot be increased adequately without much increase in cost.

Note that in developing countries such as India, there are difficulties of measuring employment, unemployment and full employment. Therefore in the Indian context, instead of full-employment level of output, we use full capacity output of the economy beyond which supply of output cannot be increased.

It is important to note that Keynes in his booklet How to Pay for the War published during the Second World War explained inflation in terms of excess demand for goods relative to the aggregate supply of their output. His notion of the inflationary gap which he put forward in his booklet represented excess of aggregate demand over full-employment output.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This inflationary gap, according to him, leads to the rise in prices. Thus, Keynes explained inflation in terms of demand-pull forces. Therefore, the theory of demand-pull inflation is associated with the name of Keynes.

Since beyond full-employment level of aggregate supply output cannot increase in response to increase in demand, this results in rise in prices under the pressure of excess demand. Aggregate supply curve, according to him, is vertical at full-employment level.

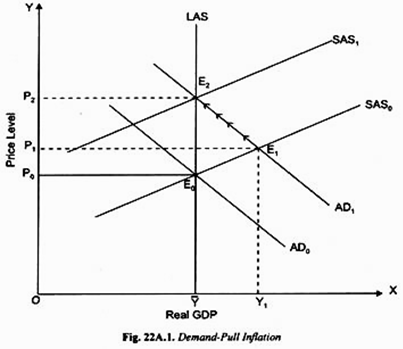

Demand-pull inflation is shown in Figure 22A.1. In the modern macroeconomics distinction is drawn between long-run aggregate supply curve (LAS) and short-run aggregate supply curve (SAS). The long-run aggregate supply curve (LAS) is a vertical line drawn at the full-employment level (i.e. at natural rate of unemployment) or in the Indian context full-capacity output level.

This full-employment level or full-capacity output is also called potential output. The short-run aggregate supply curve SAS0 slopes upward to the right which shows more supply of output is forthcoming at a higher price and is drawn with a constant wage rate. This short-run aggregate supply curve (SAS) slopes upward because with the increase in employment of labour, diminishing returns to labour occur which raises marginal cost of production.

This short-run aggregate supply curve slopes upward to the right even beyond full-employment or potential level of output. This is because, as explained earlier, even at full-employment level, some unemployment occurs due to frictional and structural factors and therefore beyond full-employment level, employment of labour can increase with reduction in natural unemployment under the pressure of aggregate demand.

It will be seen from Figure 22A. 1 that short-run aggregate supply curve SAS0 cuts long-run aggregate supply curve LAS at point E0. To begin with, aggregate demand curve AD0 intersects both short-run aggregate supply curve SAS0 and long-run aggregate supply curve (LAS) at point E0 and this shows that at point E0 there is long-run equilibrium at potential or full-employment GDP level Y and at price level P0.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Now suppose without increasing taxes government increases its expenditure on goods and services and finances it by borrowing from the Reserve Bank which in turn prints money for this purpose. As a result of increase in government expenditure, aggregate demand curve shifts to the right to AD1 which intersects the short-run aggregate supply curve SAS0 at point E1 and as a result price level rises to P1 and real GDP to Y1.

It needs to be emphasized that price level has risen as a result of rightward shift in aggregate demand curve to AD1 because aggregate supply has not increased to the extent of increase in aggregate demand and thereby creating demand-supply imbalances.

If short-run aggregate curve had been horizontal line through point E0, the aggregate supply would have increased by an equal amount to the increase in aggregate demand when aggregate demand curve shifts to right to AD1. Thus, the price level has risen because aggregate demand has increased relatively more than the aggregate supply, that is, due to demand-supply imbalances.

However, the response to the initial increase in aggregate demand to AD1 does not stop at point E1. It may be recalled that in drawing short-run aggregate supply curve wage rate of labour is kept constant. Now, the rightward shift in aggregate demand curve to AD1 has caused the price level to rise from P0 to P1 and real gross domestic output (GDP) has risen to Y1.

This rise in price level, the wage rate remaining constant, would cause decline in workers’ real wage rate, W/P1 < W/P0 where P1 > P0. When workers realize that their real wage has fallen as a result of increase in aggregate demand causing rise in price level, they will demand higher wages in their negotiations with their employers which are likely to be conceded to.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Further, as pointed out above, equilibrium to the right of potential GDP level Y implies that unemployment has fallen below the natural rate of unemployment and will cause shortage of labour which implies wage rate will rise. When wages are raised by the firms short-run aggregate supply curve will shift upward and this process of shifting short-run aggregate supply curve upward will continue until it reaches SAS1 which cuts the new aggregate demand curve AD1 at point E2 that lies at the long-run supply curve LAS and as a result price level further rises to P2.

Equilibrium between aggregate demand and aggregate supply with price as P2 and at point E2 on the long-run average supply curve LAC the wage rate has risen by E0E2 equal to the rise in price level by P0P2. Thus, real wage has been restored at the level prior to increase in aggregate demand from AD0 to AD1.

Note that equilibrium and wage rate at point E1 on the short-run average supply curve will move to point E2 at the long-run average supply curve not with a single jump but through various steps of wage adjustment and upward shifting of short-run aggregate supply curve. That is why we depicted this movement from point E1 to point E2on the LAS through various arrows.

Note that not only there is shifting upward of short-run average supply curve to restore previous level of real wage rate but also real GDP has returned to potential or full-employment GDP level Y.

Demand-Pull Inflation Process to Cause Continuous Rise in Price Level:

We have explained above the process of demand-pull inflation when for a given increase in aggregate demand, price level has eventually gone up to price level P2 and wages have risen enough to restore the real wage to its previous full-employment level.

But, as noted above, inflation is a continuous increase in the price level and not a one-time jump in the price level in response to a given increase in aggregate demand. For sustained or persistent inflation to take place the continuous increase in aggregate demand must occur. In our example aggregate demand can persistently increase if a government has a large persistent budget deficit that it finances by borrowing from the Central Bank or alternatively borrowing from the market year after year.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Besides, continuous increase in aggregate demand can occur if quantity of money is persistently increased by the Central Bank of the country. In these two cases aggregate demand increases year after year causing price level to rise persistently.

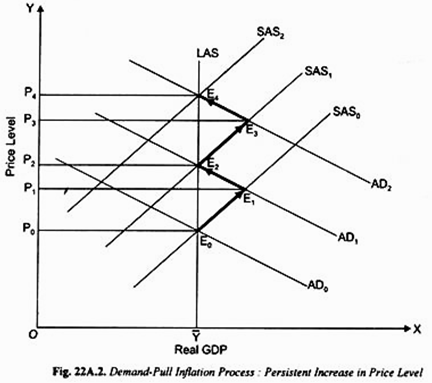

This continuous rise in price level is shown in Fig. 22A.2 in which we have assumed that government runs the budget deficit year after year and finances it by borrowing from the Central Bank (that is, government sells its bonds to the Central Bank which prints new money to pay for these bonds).

As a result, aggregate demand increases year after year bringing about continuous rise in price level. Initially, the equilibrium is at point E0 at which an aggregate demand curve AD0 intersects long- run aggregate supply curve (LAS) as well as short-run aggregate supply curve SAS0.

Now suppose that increase in government expenditure financed by borrowing from the Central Bank shifts aggregate demand curve to AD1 which intersects the short-run aggregate supply curve SAS0 at point E1 raising the price level to P1. As explained above, with rise in price level to P1 real wages of labour will fall and they will demand higher wages.

As a result of rise in wage rate over a number of stages or steps short-run aggregate supply curve (SAS) shifts to the left till it intersects the new aggregate demand curve AD1 at point E2that lies at the long-run aggregate supply curve (LAS). With this equal rise in price level and wage rate, real wage rate of workers is restored.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Now suppose next year the government again incurs a budget deficit and finances its further increase in expenditure by borrowing more from the Central Bank. With this aggregate demand curve shifts to the right to AD2 and cuts the short-run aggregate supply curve SAS1 at E3 and causes price level to rise further to P3 as shown in Fig. 22A.2.

The rise in price level will cause the fall in real wage rate of workers who will demand increase in their money wage rate further. When higher money wage rate is conceded to, short-run aggregate supply curve will start shifting to the left and the process will eventually end when short-run aggregate supply curve has shifted to the position SAS2 which intersects aggregate demand curve AD2 at point E4 at which price level has risen to P4 and with that real wage rate of workers is restored at full-employment level with potential GDP equal to Y.

If government further increases its expenditure next year and finances it by borrowing from the Central Bank, price level will further rise. In this way there is continuous inflation triggered by increase in government expenditure and the operation of wage price spiral under the pressure of increase in aggregate demand.

In Fig. 22A.2 we have traced the rise in price level through arrows as aggregate demand increases and short-run aggregate supply curve shifts to the right as a result of increase in money wage rate.

Inflationary Expectations:

Inflationary expectations are an important cause of inflation. The expectations of future prices play a significant role in decision-making by firms regarding price and output. If a firm expects that its rival firms will raise their prices, it may also raise its own price in anticipation.

Suppose inflation has been occurring at a rate of 8 per cent per annum in the past, a firm will expect this inflation rate to continue in future too and therefore it will raise its price by 8 per cent. If every firm expects that other firms will raise their prices by 8 per cent, every one will raise its prices by 8 per cent.

As a result, inflation rate of about 8 per cent will occur. This is how inflationary expectations cause inflation. Elaborating on this, Case and Fair write, “Expectations can lead to an inertia that makes it difficult to stop an inflationary spiral. If prices have been rising and if people’s expectations are adaptive, that is, if they form their expectations on the basis of past pricing behaviour – that firms may continue raising prices even if demand is slowing.” Therefore, to check inflation, steps should be taken to break the inflationary expectations.

Cost-Push Inflation:

We can visualize situations where even though there is no increase in aggregate demand, prices may still rise. This may happen if there is initial increase in costs independent of any increase in aggregate demand.

The four main autonomous increases in costs which generate cost-push inflation have been suggested:

1. Oil Price Shock

2. Farm Price Shock

3. Import Price Shock

4. Wage-Push Inflation

Cost-Push inflation is also called supply-side inflation:

1. Oil Price Shock:

In the seventies the supply shocks causing increase in marginal cost of production became more prominent in bringing about cost-push inflation. During the seventies, rise in prices of energy inputs (hike in crude oil price made by OPEC resulting in rise in prices of petroleum products). The sharp rise in world oil prices during 1973-75 and again in 1979-80 produced significant supply shocks resulting in cost-push inflation.

The sharp rise in the price of oil leads to inflation in all oil-importing countries. The rise in oil price also occurred in 1990, 1999-2000 and again in 2003-08 which resulted in rise in rate of inflation in oil-importing countries such as India.

In recent years, there have been a good deal of fluctuations in oil prices; in some periods they go up and in some others they go down. It may be noted that rise in oil prices not only gives rise to the increase in inflation, but also adversely affects the balance of payments raising current account deficit of the oil-importing countries such as India.

2. Farm Price Shock:

Cost-push inflation can also come about from increase in prices of other raw materials, especially farm products, in economies such as that of India where they are of greater importance. In India when monsoon is not adequate or come very late or when weather conditions are quite unfavourable, they reduce the supply of agricultural products and raise their prices.

These farm products are raw materials for various industries such as sugar industry, other agro-processing industries, cotton textile industry, jute industry and as a result when prices of farm products rise they lead to rise in prices of goods which use the farm products as raw materials. This is farm price shock causing cost-push inflation.

Even rise in food prices or what is called food inflation is caused by supply-side factors such as inadequate rainfall or untimely monsoon and other adverse weather conditions and inadequate availability of fertilizers which lead to reduction in output of food grains is the example of cost-push or supply-side inflation.

3. Import Price Shock:

These days currencies of most countries of the world are flexible, that is, determined by demand for and supply of a currency and they can appreciate or depreciate every month in terms of the US dollar. For example, when the Indian rupee depreciates, more rupees are required to buy one US dollar and therefore in terms of rupees, imports become costlier.

The Indians who import raw materials for industries such as petroleum products, coal, machines and other equipment, oilseeds, fertilizers, Indian consumers who imports gold, cars and other final products have to pay higher prices in terms of rupees when Indian rupee depreciates against US dollar.

This raises the cost of production of the producers who in turn raise the prices of final products produced by them. This inflation is the result of import price shock. Thus depreciation of rupee causes cost-push inflation. For example, in the month of June 2013, there was sharp depreciation of the Indian rupee. The value of rupee fell by about 9.5 per cent in this single month from about Rs. 56 to a US dollar in the first week of June 2013 to around Rs. 61 to a dollar in the last week of June 2013.

4. Wage Push Inflation:

It has been suggested that the growth of powerful trade unions is responsible for the spread of inflation, especially in the industrialized countries. When trade unions push for higher wages which are not justifiable either on grounds of a prior rise in productivity or of cost of living they produce a cost-push effect.

The employers in a situation of high demand and employment are more agreeable to concede to these wage claims because they hope to pass on these rises in costs to the consumers in the form of hike in prices. If this happens we have cost-push inflation.

It may be noted that as a result of cost-push effect of higher wages, short-run aggregate supply curve of output shifts to the left and, given the aggregate demand curve, results in higher price of output.

Cost-Push Inflation Spiral:

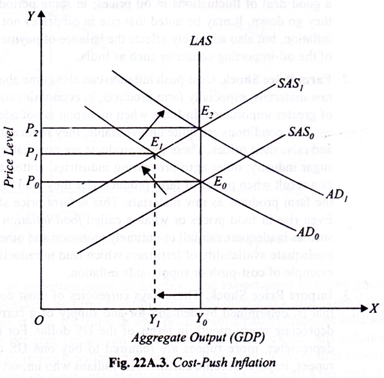

Let us consider Figure 22A.3 where to begin with aggregate demand curve AD0 and short-run aggregate supply curve SAS0 intersect at point E0 and determine price level PQ and output level Y0. Further suppose that Y0 is the full-capacity (i.e., full-employment) level of output and therefore long-run aggregate supply curve LAS is vertical at Y0 level of output.

Suppose there is increase in oil prices which causes shifts in short-run aggregate supply curve to the left from SAS0 to SAS1. As a result, price level rises to P1 but output falls from Y0 to Y1. With decline in output unemployment will also increase.

Thus cost-push inflation not only causes rise in price level (or inflation) but also brings about fall in GDP level. The rise in price level or inflation and simultaneously fall in GDP level is called stagflation. Thus cost-push inflation results in stagflation.

When the real GDP decreases as a result of cost- push inflation in the first stage, the unemployment will also rise. When unemployment emerges there is a huge hue and cry by the workers who are rendered unemployed.

In such a situation either the Central Bank will respond by increasing the money supply to raise aggregate demand or the government will increase its expenditure to provide fiscal stimulus to aggregate demand. As a result of either of these responses, aggregate demand curve shifts to the right from AD0 to AD1.

With this, the economy moves from equilibrium position E1 to the equilibrium position E2. As will be seen from Fig. 22A.3, as a result of this increase in aggregate demand while real GDP has returned to the potential GDP level Y0, price level has further risen to P2 (that is, more inflation will occur).

But the inflationary process of cost-push inflation will not stop at equilibrium point E2. If there is further rise in any of the cost-push factors such as rise in oil price, increase in price of farm output, import price shock or wage rate increase takes place short-run aggregate supply curve SAS will shift further to the left of SAS1 and intersects the aggregate demand curve AD1 to the left of the long-run aggregate supply curve LAS causing further rise in price level or inflation above P2 and fall in GDP from the potential level Y0 resulting again in unemployment of workers.

To restore full employment and raise GDP to the potential level Y0, the Central Bank will further increase the money supply or the government will further increase its expenditure. As a result, aggregate demand curve will again shift to the right of AD1.

With this, GDP level will be back at the potential level Y0 and full employment of workers will be restored but price level or inflation will further rise. In this way cost-push inflation spiral will work to cause sustained or persistent inflation.

Many economists think inflation in the economy is generally caused by the interaction of the demand pull-and cost-push factors. The inflation may be started in the first instance either by cost-push factors or by demand-pull factors, both work and interact to cause sustained inflation over time.

Thus, according to Matchup, “There cannot be a thing as cost-push inflation because without an increase in purchasing power and demand, cost increases will lead to unemployment and depression, not to inflation”. Likewise, Cairn-cross writes, “There is no need to pretend that demand and cost inflation do not interact or that excess demand does not aggregate wage inflation, of course it does.”

Monetarist Theory of Inflation:

We have explained above the Keynesian theory of demand-pull inflation. It is important to note that both the original quantity theorists and the modern monetarists, prominent among whom is Milton Friedman, also explain inflation in terms of excess demand for goods and services.

But there is an important difference between the monetarist view of demand-pull inflation and the Keynesian view of it. Keynes explained inflation as arising out of real sector forces. In his model of inflation excess demand comes into being as a result of autonomous increase in expenditure on investment or consumption, or increase in government expenditure on goods and services, that is, the increase in aggregate expenditure or demand occurs independent of any increase in the supply of money.

On the other hand, monetarists explain the emergence of excess demand and the resultant rise in prices on account of the increase in money supply in the economy. To quote Friedman, “Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon….. and can be produced only by a more rapid increase in the quantity of money than in output.”

Friedman holds that when money supply is increased in the economy, then there emerges an excess supply of real money balances with the public over the demand for money. This disturbs the equilibrium. In order to restore the equilibrium, the public will reduce the money balances by increasing expenditure on goods and services.

Thus, according to Friedman and other modern quantity theorists, the excess supply of real monetary balances results in the increase in aggregate demand for goods and services. If there is no proportionate increase in output, then extra money supply leads to excess demand for goods and services. This causes inflation or rise in prices.

The whole argument can be presented in the following scheme:

Ms > kPY →AD ↑ → P↑ …(1)

where Ms stands for quantity of money and P for the price level, Therefore, Ms/P represents real cash balances. Y stands for national income and k for the ratio of income which people want to keep in cash balances. Hence kPY represents demand for cash balances (i.e., demand for money), AD represents aggregate demand for or aggregate expenditure on goods and services which is composed of consumption demand (C) and investment demand (I).

In the above scheme it will be seen that when the supply of money (Ms) is increased, it creates excess supply of real cash balances. This is expressed by Ms > kPY. This excess supply of real money balances leads to (→) the rise (↑) in aggregate demand (AD). Then increase (↑) in aggregate demand (AD) leads to (→) the rise (↑) in prices (P).

Friedman’s monetarist theory of inflation can be better explained with quantity equation (P = MV/Y = M/Y . 1/k) written in percentage form which is written as below taking For k as constant

where ∆P/P is the rate of inflation, ∆Ms/Ms

is the rate of growth of money supply and ∆Y/Y is the rate of growth of output. Thus, according to equation (2), rate of inflation (∆P/P) of money supply (∆Ms/M) and rate of growth of output (∆Y/Y), with velocity of circulation (V) or k remaining constant. Friedman and other monetarists claim that inflation is predominantly a monetary phenomenon which implies that changes in velocity and output are small.

It thus follows that when money supply increases, it causes disturbance in the equilibrium, that is, Ms > kPY. According to Friedman and other monetarists, the reaction of the people would be to spend the excess money supply on goods and services so as to bring money supply in equilibrium with the demand for money.

This leads to the increase in aggregate demand or expenditure on goods and services which, k remaining constant, will lead to the increase in nominal national income (PY). They further argue that the real national income or aggregate output (i.e., Y in the demand for money function stated above) remains stable at full-employment level in the long run due to the flexibility of wages.

Therefore, according to Friedman and his followers (modern monetarists), in the long run, the increase in nominal national income (PY) brought about by the expansion in money supply and resultant increase in aggregate demand will cause a proportional increase in the price level.

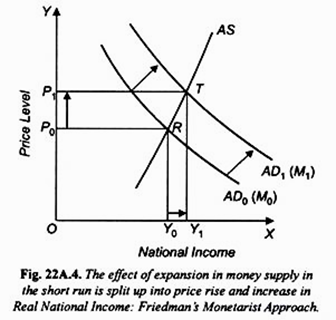

However, in the short run, like Keynesians, they believe that the economy may be working at less than full employment, that is, in the short run there may prevail excess capacity and unemployment of labour so that expansion in money supply and consequent increase in nominal income partly induces expansion in real income (Y) and partly results in rise in the price level as shown in Fig. 22A.4.

To what extent price level increases depends upon the elasticity of supply or aggregate output in the short run. It will be seen from Fig. 22A.4 that effect of increase in money supply from M0 to M1 and resultant increase in aggregate demand curve for goods and services from AD0 to AD1 is split up into the rise in price level (from P0 to P1) and the increase in real income or aggregate output (from Y0 to Y1).

It should be noted that Friedman and other modem quantity theorists believe that in the short run full employment of labour and other resources may not prevail due to recessionary conditions and, therefore, they admit the possibilities of increase in output. But they emphasize that in the short run when the growth in money supply is greater than the growth in output, the result is excess demand for goods and services which causes rise in prices or demand-pull inflation.

It follows from above that both Friedman and Keynesians explain inflation in terms of excess demand for goods and services. Whereas Keynesians explain the emergence of excess demand due to the increase in autonomous expenditure, independent of any increase in money supply. Friedman explains that inflation is caused by proportionately greater increase in money supply than the increase in aggregate output. In both views inflation is of demand-pull variety.

Money and Sustained Inflation:

Many economists believe in the monetarist view of inflation. Increase in money shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right and if the economy is operating at full capacity (i.e., along the vertical part of the aggregate supply curve), the upward shift in aggregate demand curve will cause price level to rise. A big drawback of this approach is that it assumes that supply of output does not increase sufficiently to counter this effect of expansion in money supply on aggregate demand.

In this context there is a need to distinguish between a one-time increase in the price level and sustained inflation which occurs when the general price level continues to rise over a long period of time. It is generally believed by most of the economists that whatever be the initial cause of inflation (demand- pull, cost-push or inflationary expectations), for the price level to continue rising, period after period, it must be accommodated by expansion in money supply.

Sustained inflation is therefore considered as a purely monetary phenomenon. It is not possible for the price level to continue rising if the money supply remains constant. The increase in money supply continues shifting the aggregate demand curve to the right; if aggregate supply does not increase sufficiently to match the increase in aggregate demand, price level will continue rising.

Sustained inflation can be better understood when Government increases its expenditure without raising taxes. This leads to the increase in aggregate demand which, aggregate supply remaining constant, will cause a rise in price level. It is important to know what happens when the price level rises. The higher price level raises the demand for money to rise for transaction purposes.

With supply of money remaining constant, the greater demand for money causes interest rate to rise. The rise in interest rate crowds out private investment. If the Central Bank of a country wants to prevent the fall in the private investment, it will expand the money supply to keep the interest constant. But this expansion in money supply through its effect on aggregate demand will cause the price level to rise further if increase in more supply of output is not possible.

This further rise in price level will again cause greater demand for money leading to higher interest rate. And the Central Bank, if it is committed to keep the interest rate constant so that private investment does not decline, will further expand the money supply which will cause further inflation. This process could lead to hyperinflation which represents a rapid and continuous rise in price level, period after period.

The historical experience shows this hyperinflation in some countries when the Central Bank or Government of these countries kept pumping in more and more money either to finance its persistent budget deficit of the government year after year of to prevent the interest rate to rise. However, as mentioned above, hyperinflation disrupts the payment system and people’s loss of credibility of the currency. This leads to a deep crisis in the economy. If hyperinflation is to be avoided, then the process of rapid expansion in money supply must be halted.

Structuralist Theory of Inflation:

Structuralist theory, another important theory of inflation, is also known as structural theory of inflation and explains inflation in the developing countries in a slightly different way. The Structuralist argue that increase in investment expenditure and the expansion of money supply to finance it are the only proximate and not the ultimate factors responsible for inflation in the developing countries.

According to them, one should go deeper into the question as to why aggregate output, especially of food grains, has not been increasing sufficiently in the developing countries to match the increase in demand brought about by the increase in investment expenditure and money supply. Further, they argue why investment expenditure has not been fully financed by voluntary savings and as a result excessive deficit financing has been done.

Structuralist theory of inflation has been put forward as an explanation of inflation in the developing countries especially of Latin America. The well-known economists, Myrdal and Streeten, who have proposed this theory have analyzed inflation in these developing countries in terms of structural features of their economies. Recently Kirkpatrick and Nixon have generalized this structural theory of inflation as an explanation of inflation prevailing in all developing countries.

Myrdal and Streeten have argued that it is not correct to apply the highly aggregative demand- supply model for explaining inflation in the developing countries. According to them, there is a lack of balanced integrated structure in them where substitution possibilities between consumption and production and inter-sectoral flows of resources between different sectors of the economy are not quite smooth and quick so that inflation in them cannot be reasonably explained in terms of aggregate demand and aggregate supply.

In this connection it is noteworthy that Prof. V.N. Pandit of Delhi School of Economics has also felt the need for distinguishing price behaviour in the Indian agricultural sector from that in the manufacturing sector.

Thus, it has been argued by the exponents of structuralism theory of inflation that economies of the developing countries of Latin America and India are structurally underdeveloped as well as highly fragmented due to the existence of market imperfections and structural rigidities of various types.

The result of these structural imbalances and rigidities is that whereas in some sectors of these developing countries we find shortages of supply relative to demand, in others under utilisation of resources and excess capacity exist due to lack of demand. According to structuralists, these structural features of the developing countries make the aggregate demand-supply model of inflation inapplicable to them.

They therefore argue for analysing dis-aggregative and sectoral demand-supply imbalances to explain inflation in the developing countries. They mention various sectoral constraints or bottlenecks which generate the sectoral imbalances and lead to rise in prices.

Therefore, to explain the origin and propagation of inflation in the developing countries, the forces which generate these bottlenecks or imbalances of various types in the process of economic development need to be analyzed. A study of these bottlenecks is therefore essential for explaining inflation in the developing countries.

These bottlenecks are of three types:

(1) Agricultural bottlenecks which make supply of agricultural products inelastic,

(2) Resources constraint or Government budget constraint, and

(3) Foreign exchange bottleneck. Let us explain briefly how these structural bottlenecks cause inflation in the developing countries.

Agricultural Bottlenecks:

The first and foremost bottlenecks faced by the developing countries relate to agriculture and they prevent supply of food grains to increase adequately. Of special mention of the structural factors are disparities in land ownership, defective land tenure system which act as disincentives for raising agricultural production in response to increasing demand for them arising from increase in people’s incomes, growth in population and urbanization.

Besides, use of backward agricultural technology also hampers agricultural growth. Thus, in order to control inflation, these bottlenecks have to be removed so that agricultural output grows rapidly to meet the increasing demand for it in the process of economic development.

Resources Gap or Government’s Budget Constraint:

Another important bottleneck mentioned by structuralist relates to the lack of resources for financing economic development. In the developing countries planned efforts are being made by the Government to industrialise their economies. This requires large resources to finance public sector investment in various industries. For example, in India, huge amount of resources were used for investment in basic heavy industries started in the public sector.

But socio-economic and political structure of these countries is such that it is not possible for the Government to raise enough resources through taxation, borrowing from the public, surplus generation in the public sector enterprises for investment in the projects of economic development. Revenue raising from taxation has been relatively very small due to low tax base, large scale tax evasion, inefficient and corrupt tax administration.

Consequently, the government has been forced to resort to excessive deficit financing (that is, creation of new currency) which has caused excessive growth in money supply relative to increase in output year after year and has therefore resulted in inflation in the developing countries. Though rapid growth of money supply is the proximate cause of inflation, it is not the proper and adequate explanation of inflation in these economies.

For proper explanation of inflation one should go deeper and enquire into the operation of structural forces which have caused excessive growth in money supply in these developing economies. Besides, resources gap in the private sector due to inadequate voluntary savings and underdevelopment of the capital market have led to their larger borrowings from the banking system which has created excessive bank credit for it.

This has greatly contributed to the growth of money supply in the developing countries and has caused rise in prices. Thus, Kirkpatrick and Nixon write, “The increase in the supply of money was a permissive factor which allowed the inflationary spiral to manifest itself and become cumulative—it was a system of the structural rigidities which give rise to the inflationary pressures rather than the cause of inflation itself.”

Foreign Exchange Bottleneck:

The other important bottleneck which the developing countries have to encounter is the shortage of foreign exchange for financing needed imports for development. In the developing countries ambitious programme of industrialisation is being undertaken. Industrialisation requires heavy imports of capital goods, essential raw materials and in some cases, as in India, even food grains have been imported. Besides, imports of oil on a large scale are being made.

On account of all these imports, import expenditure of the developing countries has been rapidly increasing. On the other hand, due to lack of export surplus, restrictions imposed by the developing countries, relatively low competitiveness of exports, the growth of exports of the developed countries has been sluggish.

As a result of sluggish exports and mounting imports, the developing countries have been facing balance of payment difficulties and shortage of foreign exchange which at times has assumed crisis proportions. This has affected the price level in two ways.

First, due to foreign exchange shortage domestic availability of goods in short supply could not be increased which led to the rise in their prices. Secondly, in Latin American countries as well as in India and Pakistan, to solve the problem of foreign exchange shortage through encouraging exports and reducing imports devaluation in the national currencies had to be made. But this devaluation caused rise in prices of imported goods and materials which further raised the prices of other goods as well due to cascading effect. This brought about cost-push inflation in their economies.

Physical Infrastructural Bottlenecks:

Further, the structuralists point out various bottlenecks such as lack of infrastructural facilities, i.e., lack of power, transport and fuel which stands in the way of adequate growth in output. At present in India, there is acute shortage of these infrastructural inputs which are hampering growth of output.

Sluggish growth of output on the one hand, and excessive growth of money supply on the other have caused what is now called stagflation, that is inflation which exists along with stagnation or slow economic growth.

According to the structuralist school of thought, the above bottlenecks and constraints are rooted in the social, political and economic structure of these countries. Therefore, in its view a broad-based strategy of development which aims to bring about social, institutional and structural changes in these economies is needed to bring about economic growth without inflation.

Further, many structuralists argue for giving higher priority to agriculture in the strategy of development if price stability is to be ensured. Thus, we see that structuralist view is greatly relevant for explaining inflation in the developing countries and for the adoption of measures to control it. Let us further elaborate the causes of inflation in the developing countries.

The Social Costs and Effects of Inflation:

Having discussed the so called inflation fallacy we proceed to explain in detail the social cost and effects of inflation. Apart from reducing the purchasing power of people’s incomes, inflation inflicts some other costs on the society. To explain such costs of inflation it is necessary to distinguish between anticipated inflation and unanticipated (i.e., unexpected) inflation. As noted above, in case of anticipated inflation, the expected rise in price level is taken into account while making economic transactions, for example, in negotiating wage rate of labour etc.

Costs of Anticipated Inflation:

Suppose in an economy there has been annual inflation rate of 5 per cent for a long time in the past and everybody expects that this 5 per cent rate of inflation will continue in the future too. In such a case all contracts made by the people such as loan agreements with borrowers, wage contracts with labour, property lease contracts will provide for 5 per cent annual rise in rates of interest, wages, rent to compensate for inflation of that order.

That is, in any contract in which passage of time is involved 5 per cent rate of inflation will be taken into account and rates will be agreed to rise per period equal to the anticipated rate of inflation. If rates of interest, wages, rent etc. are agreed to rise at the anticipated rate of inflation, then there will be no cost of inflation except the following two types of costs – shoe-leather costs and menu costs which are not very high.

We explain below both these types of costs:

1. Shoe-leather Costs:

This type of cost occurs because on account of inflation cost of holding money in the form of currency (i.e., notes and coins) rises with the increase in inflation rate. Such cost arises because no interest is paid on holding currency, while money kept in deposits with the bank or used for keeping bonds earns interest.

When inflation rate rises, the nominal interest rate on bank deposits rises, the interest lost by holding currency by the people therefore increases. In order to reduce the cost of holding currency people will tend to reduce their holdings of currency for transaction purposes. Accordingly, at a time people will hold less currency with them and keep as long as possible greater amount of money in bank deposits that yield interest.

Therefore, rather than withdrawing a large amount of currency from banks at a time, they will withdraw less money which is sufficient for meeting daily expenses for a few days, say for a week. But for doing so the people will make more trips to withdraw cash. More trips to a bank in a month involves greater cost to the people.

These costs have to be incurred on spending on petrol if car is used for making trips, more wear and tear of car, the time spent for making a trip. These costs of making more trips to the bank for withdrawing currency is metaphorically called shoe-leather costs of inflation, as walking to banks more often one’s shoes wear out more rapidly and one has to spend money on new shoes more often.

2. Menu Costs:

The second type of anticipated inflation is menu costs, a term derived from a restaurant’s cost of printing a new menu. Menu costs arise because high inflation requires them to change their listed prices more often. Changing prices is somewhat more expensive because the firms have to print new catalogues listing new prices and distribute them among their customers. They have even to incur expenditure on advertisements to inform the public about their new prices.

3. Macroeconomic Inefficiency in Resource Allocation:

A third cost of inflation arises because firms having menu costs change their prices quite infrequently. Given the reluctance to change prices frequently, the higher the rate of inflation, the greater the variability in relative prices of a firm. Suppose a firm issues a new catalogue listing prices of its products once in a year, say in the month of January of every year.

If during the year inflation occurs, there will be change in the relative prices of a firm to the general price level. If inflation rate of one per cent per month takes place in a year the firm’s relative prices to the general price level will fall by 12 per cent by the end of the year.

As a result, his sales will tend to be lower in the early part of the year (when its prices are relatively high) and higher in the later part of the year (when its prices are relatively low). Thus when due to inflation relative prices of a firm vary during a year as compared to the overall price level, it causes distortion in production and therefore leads to microeconomic inefficiencies in resource allocation.

4. Inconvenience of Living:

Lastly, another social cost of inflation is the inconvenience of living in a world with a changing price level. Money is the yardstick with which we measure the value of transactions. When inflation is taking place the value of money changes and as a result it becomes difficult to correctly estimate the value of transactions in real terms every time a transaction is made during a year.

The rising price level makes it difficult to make optimal decisions about saving and investment and thus do the rational financial planning covering a long period of time. To quote Mankiw, “A dollar saved today and invested at a fixed nominal interest rate will yield a fixed dollar amount in the future. Yet the real value of that dollar amount – which will determine the retiree’s living standard – depends on the future price level. Deciding how much to save would be much simpler if people could count on the price level in 30 years being similar to its level today.”

Conclusion:

Taking account of all costs of anticipated inflation one finds that the cost of anticipated inflation are quite small or trivial and if these alone are considered, it is then surprising why inflation is a matter of serious concern for the policy makers and politicians.

In our opinion the above view of costs of inflation does not consider the true cost of inflation which, as mentioned above, refers to the reduction in purchasing power or real incomes of the people which lowers their standard of living. Besides, there is ample cross-country evidence that high rates of inflation lead to low rate of sustained economic growth.

It may be further noted that in the above analysis of cost of inflation it is assumed that there is only small to moderate inflation rate, say a single digit rate of inflation occurs so that it does not disrupt the payment system. With such a low to moderate inflation, costs of inflation are small. The hyperinflation has more harmful effect as it disrupts the payment system which leads to the collapse of the economy.

Cost of Unanticipated Inflation:

Unanticipated inflation has a more substantial and harmful effect as compared to the cost of anticipated inflation rate. The significant effect of unanticipated inflation is that it arbitrarily re-distributes wealth among individuals. Consider the value of assets fixed in nominal terms.

Between 1995 and 2006, price level in India rose by about 100 per cent. This implies that those who held claims on assets fixed in nominal terms in 1996, their real value in terms of purchasing power would have declined significantly. Thus, a person who bought government bond of 10 years maturity with a face value of Rs. 1000 bearing 8 per cent nominal interest rate in 1996 will find that Rs. 1000 he gets back in 2006 has far less value than when he purchased the bond in 1996.

Similarly, unanticipated inflation harms the individuals, who retire on pensions fixed in rupee terms. After some years of inflation, the real value or purchasing power of the fixed nominal pension will greatly decline and will therefore reduce his standard of living in his old age. Thus inflation hurts individuals with fixed pensions.

Workers and the private firms often agree on fixed nominal pension payable to the workers after retirement. Workers are greatly harmed when inflation is higher than anticipated. Likewise, higher than anticipates an inflation rate hurts the creditors who give loans to the others and get back the principal amount after the stipulated period. Thus inflation redistributes wealth in favour of debtors.

Bad Effects of Inflation on Long-term Economic Growth: An Important Social Cost of Inflation:

An important social cost of inflation, especially in developing countries, is its bad effect on long- run economic growth. Some economists have argued that inflation of a creeping or mild variety has a tonic effect on the long-run economic growth. In their support they give the example of today’s industrialized countries in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries when the rate of growth of output had been more rapid during long periods of inflation witnessed in these countries.

The driving force in the process of economic growth, according to them, has been high profit margins created by inflation. They argue that wages lag behind the rise in general price level and thus creating higher profit margins for businessmen and industrialists. This tends to increase the profit share in national income.

The businessmen and industrialists who receive profits as income belong to the upper income brackets whose propensity to save is higher as compared to the workers. As a result, savings go up which ensures higher rate of investment. With greater rate of investment more accumulation of capital is made possible. More rapid capital accumulation generates a higher rate of long-run economic growth.

Looking at the problem from an alternative angle, with wages lagging behind rise in prices, inflation causes a large shift of resources away from the production of consumer goods for the wage earners to the production of capital goods. The higher rate of expansion in capital stock raises the growth of productive capacity of the economy and productivity of labour. This generates rapid economic growth.

However, it is now widely recognized that, far from encouraging savings and generating higher rate of economic growth, inflation slows down the rate of capital accumulation. There are several reasons responsible for this. First, as seen above, when due to rapid inflation value of money is declining, people will not like to keep money with themselves and will, therefore, be eager to spend it before its value goes down heavily.

This raises their consumption demand and therefore lowers their saving. Besides, people find that the rapid inflation will erode the real value of their savings. This discourages them to save. Thus, inflation or rapid rise in prices serves as a disincentive to save.

Further, as a consequence of the rise in prices, a relatively greater part of the income of the people is spent on consumption to maintain their level of living and therefore little is left to be saved. Thus, not only does inflation reduce the willingness to save, it also slashes their ability to save.

Secondly, inflation or rising prices lead to unproductive form of investment in gold, jewellery, real estate, construction of houses etc. These unproductive forms of wealth do not add to the productive capacity of the economy and are quite useless from the viewpoint of economic growth. Thus, inflation may lead to more investment but much of this is of unproductive type. In this way economic surplus is frittered away in unproductive investment.

Thirdly, a highly undesirable consequence of inflation, especially in developing countries, is that it accentuates the problem of poverty in these countries. It is often said inflation is enemy number one of the poor people. Due to rising prices poor people are not able to meet their basic needs and maintain minimum subsistence level of consumption.

Thus inflation sends many people to live below the poverty line with the result that the number of people living below the poverty line increases. Besides, due to inflation, consumption of a large number of poor people is reduced much below what may be regarded as productive consumption, that is, essential consumption required to maintain health and productive efficiency. In India, rapid inflation in recent years is as much responsible for the mounting number of people below the poverty line as the lack of employment opportunities.

Fourthly, inflation adversely affects balance of payments and thereby hampers economic growth, especially in the developing countries. When prices of domestic goods rise due to inflation, they cannot compete abroad and as a consequence exports of a country are discouraged.

On the other hand, when domestic prices rise relatively to prices of foreign goods, imports of foreign goods increase. Thus, falling exports and rising imports create disequilibrium in the balance of payments which may, in the long run, result in a foreign exchange crisis.

The shortage of foreign exchange prevents the country to import even essential materials and capital goods needed for industrial growth of the economy. The Indian experience during 1988-92 when foreign exchange reserves declined to abysmally low level and created an economic crisis in the country, shows the validity of this argument.

There is no agreement among economists whether or not moderate or mild inflation encourages saving and therefore ensures higher rate of capital accumulation and economic growth. However, there is complete unanimity that a rapid inflation discourages saving and hinders economic growth.

However, barring the special case of hyperinflation, whether or not saving is encouraged by inflation depends on whether there exists wage lag. While there is sufficient evidence in the industrialised countries such as the U.S.A., Great Britain, France etc., about the existence of wage lag in the period before World War II, in the period after this there is no solid evidence of it. In the present wages quickly catch up with the rising prices.

Indeed, there is evidence in some developed countries that the share of profits in national income has declined and that of wages has gone up during the post-World War II period. Therefore, “To the extent that rate of long-run economic growth depends on the rate of capital accumulation, a major basis for the conclusion that inflation promotes rapid economic growth is undermined given that wages no longer lag during inflation as they apparently did in time of past.”

However, it may be noted that in the developing countries like India where labour is mostly un-organised and trade unions of labour are not strong and further there is a lack of information which causes wages lagging behind prices during periods of inflation. This itself will cause greater proportion of national income going to profits and other business incomes which should ensure higher saving rate.

However, in India, businessmen are prone to make unproductive investment in speculative activities, gold, jewellery, real estate and palatial houses whose prices rise rapidly during periods of inflation. Such kind of investment is not only counter-productive and anti-growth but is repugnant to social justice as it further accentuates inequalities in the distribution of income and wealth.

It follows from above that rising prices as a goal of monetary policy are full of disastrous consequences for the economy and the people and therefore cannot be recommended as a desirable goal for the economic policy. Rising prices often get out of hand and hyperinflation might set in which will shake the confidence of the people in the monetary and fiscal system of the country.

Further Bad Effects of Inflation:

Inflation is a very unpopular happening in an economy. Opinion surveys conducted in India, the U.S.A. and other countries reveal that inflation is the most important concern of the people as it badly affects their standard of living. The political fortunes of many political leaders (Prime Ministers and Presidents) and Governments in India and abroad have been determined by how far they have succeeded in tackling the problem of inflation.

So much so that some American presidential candidates called ‘inflation as enemy number one’. Same is the case in India where inflation is the most hotly debated issue during the general elections for Parliament and Assemblies. A high rate of inflation makes the life of the poor very miserable. It is, therefore, described as anti-poor.

It redistributes income and wealth in favour of some and greatly harms others. By making the rich richer and the poor poorer, it militates against social justice. Besides, inflation lowers national output and employment and impedes long-run economic growth, especially in developing countries like India. We shall discuss below all these effects of inflation.

Anticipated and Unanticipated Inflation:

The difference between anticipated inflation and unanticipated inflation is of crucial importance as the effects of inflation, especially its redistributive effect, depend on whether it is anticipated or not. If rate of inflation is anticipated, then people take steps to make suitable adjustments in their contracts to avoid the adverse effects which inflation could bring to them.

For example, if a worker correctly anticipates the rate of inflation in a particular year to be equal to 10 per cent and if his present wage rate is Rs. 5000 per month, he can enter into contract with the employer that to compensate for the 10 per cent rise in prices his money wage per month next year be raised by 10 per cent so that next year he gets Rs. 5500 per month. In this way he has been able to prevent the erosion of his real income with the automatic revision of his money wage depending on the anticipated rate of inflation.

Take another example. You lend Rs. 10,000 to a person at a rate of 10 per cent per annum. After a year you will receive Rs. 11,000. But if it is anticipated that during the year there will be 8 per cent rate of inflation, then 8 per cent of your income will be offset by the rise in prices that would occur so that you will get only 2 per cent real rate of interest.

Therefore, in order to receive 10 per cent real rate of interest, in view of 8 per cent anticipated inflation rate you must demand 18 per cent nominal rate of interest.

On the other hand, effects of unanticipated inflation are unavoidable because in this case you do not know what would be the rise in the price level. That is, unanticipated inflation catches you by surprise. In what follows we shall examine the effects of unanticipated inflation. The effects of inflation can be divided into three categories:

Inflation Erodes Real Incomes of the People:

To examine the effect of inflation it is important to note the difference between money income and real income. It is the change in the general price level that creates the crucial difference between the two. Money income or what is also called nominal income means the income such as wages, interest, rent received in terms of rupees.

On the other hand, real income implies the amount of goods and services which you can buy. In other words, real income means the purchasing power of your income. If your money or nominal income increases at a lower rate than the rate of rise in the general price level (i.e., the rate of inflation), you will be able to buy less goods and services, that is, your real income will decline. Real income will rise only if nominal income rises faster than the rate of inflation.

For illustration, take the case of workers who enter into contract with their employer at an agreed wage rate of Rs. 5000 per month for the period, say 5 years. Now, suppose the rate of inflation is 10 per cent per annum. This means after a year, with money wage rate of Rs. 5,000 workers will be able to buy less goods and services. That is, their real income will decrease and therefore their standard of living will fall.

Take another example. Suppose you deposit your saving of Rs. 100 in a saving account which carries 5 per cent rate of interest. After a year you will receive Rs. 105. However, if during that year rate of inflation has been 12 per cent, you will be a loser in real terms.

In fact your real interest-income will be negative as, with 12 per cent rate of inflation, Rs. 105 after a year will buy less goods and services than what you can purchase with Rs. 100 today. The above two examples clearly show that inflation reduces the purchasing power of money and thereby adversely affects real income of the people.

Effect on Distribution of Income and Wealth:

An important effect of inflation is that it redistributes income and wealth in favour of some at the cost of others. Inflation adversely affects those who receive relatively fixed incomes and benefits businessmen, producers, traders and others who enjoy flexible incomes.

Inflation brings windfall profits for the producers and traders. Thus, all do not lose as a result of inflation, rather some gain from it. We examine below how inflation redistributes income and wealth and thereby harms some people and benefits others.

Creditors and Debtors:

Unanticipated inflation harms creditors and benefits debtors and in this way redistributes income in favour of the latter. As explained above, value of money declines due to inflation. For creditors (including financial institutions such as banks and insurance companies) who enter into agreement with the borrowers to provide loans at fixed nominal rate of interest, the real value of money in terms of goods and services which they will receive at the end of the period would be much less if during the period prices rise sharply.

Thus, the debtors or borrowers gain because they would return the loan-money when its real value has declined greatly due to the unexpected rapid rate of inflation.

Fixed Income Groups:

Those who get fixed incomes and pensioners stand to lose from inflation. Workers and salaried people who earn fixed wages and salaries are hit hard by unanticipated inflation. These people often enter into contract with the employers regarding wages or salaries fixed in nominal terms. When inflation occurs, the purchasing power of their nominal incomes falls greatly causing a decline in their levels of living.

Thus, when inflation persists for some years there are demands for revision of wages and salaries. It may be mentioned that now-a-days workers and other salaried people get dearness allowances to compensate them for the rise in cost of living due to inflation. However, these dearness allowances do not fully neutralise the rise in price level and therefore they also demand revision of wages and pay scales.

Businessmen: Producers and Traders:

Businessmen, that is, entrepreneurs and traders, stand to gain by inflation. During periods of inflation, the prices of goods produced by entrepreneurs rise relatively faster than the cost of production because wages lag behind the rise in prices of goods. Consequently, inflation increases the profits of businessmen.

The value of the inventories or stocks of goods and materials kept by the entrepreneurs and traders increases due to rise in prices of goods which brings about an increase in their profits.

Wealth Holders of Cash, Bonds and Debentures:

Inflation also adversely affects wealth holders who hold their wealth in the form of cash money, demand deposits, saving and fixed deposits and interest-bearing bonds and debentures. These wealth holders are severely hurt by inflation as inflation reduces the real value of their wealth.

Saving and demand deposits, bonds and debentures represent assets whose value is fixed in terms of money. The rise in prices reduces the purchasing power of these fixed-value money assets such as saving and time deposits, bonds and debentures which bear a fixed nominal rate of interest.

Inflation, therefore, reduces the real rate of interest earned by them. Consequently, it has been observed that during periods of rapid inflation people try to convert their holdings of money and near money into goods and physical property so as to avoid the loss due to inflation.

It may also be noted that if inflation is anticipated and all expect equal rates of inflation the nominal rates of interest are adjusted upward so as to obtain targeted real rate of interest. Thus, if creditors want real rate of interest equal to 10 per cent and anticipate rate of inflation is equal to 8 per cent, they will try to have nominal rate of interest fixed at 18 per cent.

This is known as Fischer effect which states that market or nominal rate of interest is equal to the real rate of interest (based on productivity of capital and rate of time preference) plus the anticipated rate of inflation. Thus nominal rate of inflation includes what is called inflation premium to prevent the erosion of purchasing power due to inflation.

Loss of Economic Efficiency:

It is generally believed that inflation causes misallocation of resources and therefore results in loss of economic efficiency. Inflation causes distortions in prices which misallocate resources and result in inefficiency. This distortion in prices occurs because, as a result of inflation, all prices do not rise to the same extent so that there are changes in relative prices.

It may be noted that price distortions occur when prices deviate from right prices as determined by costs and demand conditions. An important example of price distortion caused by inflation is the change in real rate of interest which is the price for the use of money.

As explained above, real rate of interest is money rate of interest minus the rate of inflation. Currency and demand deposits generally do not earn any interest, that is, money rate of interest on currency and demand deposits is zero. However, when there is inflation, say at the rate of 12 per cent per annum, the real rate of interest on currency and bank deposits will become negative.

This is price distortion which causes people to unload their stocks of currency and demand deposits in times of rapid inflation and buy other assets. This leads to economic inefficiency as people have to spend real resources for trying to economies the use of currency or, in other words, to reduce their holdings of currency and demand deposits.

For example, they have to go to banks more often to withdraw their money holdings. They use up their shoes and such other things in going to banks too often and also spend a good deal of their valuable time. In times of inflation, in their bid to economies the use of currency, the business firms also spend some resources for proper management of their cash funds.

Another important price distortion caused by inflation is in respect of taxes. In a progressive income tax structure people will have to pay higher rates of taxes as their money income increases as a result of inflation. As money incomes of the people increase due to inflation, the average rate of tax automatically rises as they are pushed into higher income tax slabs.

This is generally called inflation tax. As a result of this inflation their rewards for work or other factor services go below what is justified by the real productivity of their work or other factor services. This causes misallocation of labour and other factors which create economic inefficiency and unnecessary loss of output.

It is due to this adverse effect of taxes on resources allocation that in some countries taxes are also indexed, that is, adjusted in tune with the rise in general price level so that inflation induced distortion be avoided.

Hyperinflation and Economic Crisis:

When inflation is extremely rapid, it is called hyperinflation. A hyperinflation is generally defined as inflation at the rate of 50 per cent or more per month. Some economists, prominent among them R. Dornbusch, have defined hyperinflation as rise in price level at the rate of 1000 per cent in a year.

There are several examples of hyperinflation that occurred in European countries after World Wars I and II. The most important episode of hyperinflation took place in Germany between Aug. 1922 and Nov. 1923. German inflation occurred at the rate of 322 per cent per month during this period and in the final months rate of inflation in Germany reached the highly extreme rate of 32000 per cent per month.

It may be noted that German hyperinflation was caused by deficit financing by the government (i.e., creation of new money) to finance the budget deficit during World War I when it had to pay massive reparations it had to pay to Britain and France. Argentina, Brazil, Peru and Poland all suffered from inflation rate of 1000 per cent per year for one or more years in late 1980 or 1990.

The effect of hyperinflation on national output and employment turns out to be devastating. Thus hyperinflation is generally caused when Government issues too much currency which greatly adds to the money supply in the economy.

However, some economists are of the view that even mild or moderate inflation may ultimately lead to hyperinflation. They argue that when prices go on creeping upward for some time, people start expecting that prices will rise further and value of money will depreciate.

In order to protect themselves from the fall in the purchasing power of money in the future, they try to spend money now. That is, they try to beat the anticipated price increases. This raises the aggregate demand for goods in the present. Businessmen too increase their purchases of capital goods and build up larger than normal inventories if they anticipate rise in prices.

Thus, inflationary expectations raise the pressure on prices and in this way inflation feeds on itself. Further, the rise in prices and the cost of living under the influence of rising aggregate demand prompts the workers and their unions to demand higher wages to compensate them for the rise in the prices.

During the periods of boom these demands of the workers for hike in wages are generally conceded. But rise in labour costs due to higher wages are recovered by business firms from the consumers by raising the prices of then- products.

This increase in prices gives rise to demand for further increases in wages resulting in still higher costs. Thus, cumulative wage-price inflationary spiral starts operating which may culminate in hyperinflation.

The major reason for hyperinflation is rapid growth of money supply as a result of financing budget deficits through creation of new money. During wars government expenditure increases more than the revenue. But hyperinflation does not occur during the war period as controls are imposed on prices during the war period and therefore inflation remains suppressed. When controls are lifted after the war, hyperinflation takes places as a consequence of excessive deficit financing and monetary growth during the war period.

Some economists attribute hyperinflation to the accommodation of adverse supply shocks that may take place as a result of rise in wage rates or rise in oil prices, as these supply shocks cause inflation on the one hand and unemployment or fall in GDP on the other.

To increase employment opportunities to get rid of unemployment, the government or its Central Bank increases the supply of money to raise aggregate demand. This higher aggregate demand succeeds in eliminating unemployment but generate still higher inflation. This gives rise to wage-price spiral under which every time when the price level rises, money wages are raised to restore real wages. This process goes on and ultimately ends in hyperinflation.

The Cost of Hyperinflation:

The cost of hyperinflation is much greater than the cost of moderate inflation. For example, when prices are rising at an extremely high rate, the incentives to minimise holding of currency become quite strong that result in enormous shoe-leather costs.

In the situation of hyperinflation workers are paid much more frequently, even on daily basis and people rush out to spend their wages on goods (or to convert their currency in some other form such as a foreign currency or into gold and silver) before the prices rise even more.

The greater time and energy are spent in getting rid of currency as soon as possible. Thus hyperinflation involves lot of wastes of resources and leads to disruption of production.

Hyperinflation not only has disruptive redistribute effect, it also brings about economic crisis and may even cause collapse of the economic system. Hyperinflation encourages speculative activity on the part of people and businessmen who shy away from productive activities, as they find it highly profitable to hoard both finished goods and materials on the basis of expectations of further rise in prices.

But such hoardings of goods and materials restrict the supply and availability of goods and tend to intensify the inflationary pressures in the economy. Instead of making productive investment, people and businesses tend to invest in unproductive assets such as gold and jewellery, real estate, houses etc., as a means of protecting themselves from inflation.

In the extreme when as a result of issuing too much money supply to finance government deficit or working of wage-price spiral, inflation becomes extremely rapid or what economists called hyperinflation, normal working of the economy collapses.