Equilibrium national income occurs when planned saving equals planned investment. This saving-investment statement of the equilibrium condition once became a bone of contention between the classicists and Keynes.

The debate centered around the virtue or vice of saving or consumption. The controversy between them stemmed from the determinant of saving.

Classicists believed that saving depends on the rate or interest, i.e., S = f(r). Savings, in the classical system, are interest-elastic.

Further, classicists assumed Say’s Law. The law states that “Supply creates its own demand”. The implication of the Say’s Law is that what the society saves is automatically invested. Saving is exactly matched by investment—there cannot be any discrepancy between saving and investment.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As savers and investors are assumed to be the same group of persons, actual saving and actual investment”, desired saving and desired investment are all equal. If it is so, saving is a virtue to the nation. Greater the saving, greater the prosperity of a nation. Instead of saving, if people plan to consume more it will bring disaster.

But Keynes challenged this classical contention. Keynes argued that saving depends on income, rather than the rate of interest as suggested by the classical economists. Saving is directly related to national income. Above all, Keynes demolished Say’s Law. To him, savings do not cause investment since savers and investors are two different persons in the community. Keynes went on saying further that if a nation decides to save more the nation will be struck by disaster. Increase in individual saving is not equivalent to an increase in saving of the community. In fact, what is true for an individual is not necessarily true for the society as a whole.

What will happen if an individual decides to save more and consume less? It is to be remembered here that we live in an interdependent society where reduction of consumption (or increase in saving) of one individual is tantamount to a reduction in income of another member of the society. So, saving must decline since saving depends on income. So, we can conclude that if the society plans to save more, actual saving, national income, level of employment, etc., will decline. This is known as ‘paradox of thrift’. That is why Keynes said saving may be a virtue to an individual but community saving lowers down society’s welfare.

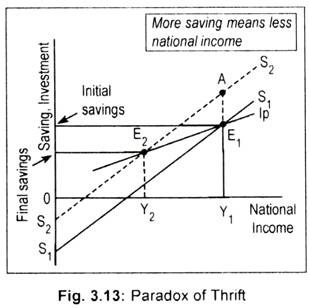

This is demonstrated in Fig. 3.13 where S1S1 is the initial saving curve. lp is the planned induced investment line. Thus, investment is no longer assumed here as an autonomous one. It is dependent on income. S1S1 and Ip curves intersect each other at point E1. Corresponding to this point, equilibrium income thus determined is E1 If people decide to save more rather than to consume, the saving function would shift to S2S2.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

So, the planned saving now rises from E1Y1 to AY1 Since aggregate demand or aggregate expenditure falls short of aggregate income, it will result in a piling up of unsold goods. Income will consequently fall. Investment will tend to decline until planned saving is equal to planned investment (i.e., point E2). Level of income is now OY2 (< OY^. The actual volume of saving will now fall from E2Y2 to E2Y2, as a result of increased desire to save. This is the paradox of thrift.

Thus, the paradox of thrift contradicts the general view that “a penny saved is a penny earned”. If so, then how does such paradox of thrift hold always? Answer is—no. Look at Fig. 3.13. If planned induced investment shifts up then equilibrium national income will increase. Suppose Ip line shifts up and cuts S2S2 line to the right of point A, then a larger income will be available. Thus, thriftiness is not unwise or unwelcome proposition. However, this result is dependent on many factors.