Let us make in-depth study of the Heckscher-Ohlin’s theory of international trade.

Introduction:

The classical comparative cost theory did not satisfactorily explain why comparative costs of producing various commodities differ as between different countries.

The new theory propounded by Heckscher and Ohlin went deeper into the underlying forces which cause differences in comparative costs.

They explained that it is differences in factor endowments of different countries and different factor-proportions needed for producing different commodities that account for difference in comparative costs. This new theory is therefore-called Heckscher-Ohlin theory of international trade.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Since there is wide agreement among modern economists about the explanation of international trade offered by Heckscher and Ohlin this theory is also called modern theory of international trade. Further, since this theory is based on general equilibrium analysis of price determination, this is also known as General Equilibrium Theory of International Trade.

It is worthwhile to note that, contrary to the viewpoint of classical economists, Ohlin asserts that there does not exist any basic difference between the domestic (inter-regional) trade and international trade. Indeed, according to him, international trade is only a special case of inter-regional trade.

Thus, Ohlin asserts that it is not the cost of transport which distinguishes international trade from domestic trade, for transport cost is present in the domestic inter-regional trade. Trade because currencies of different countries are related to each other through foreign exchange rates which determine the value or purchasing power of different currencies.

Ohlin, therefore, regards different nations as mere regions separated from each other by national frontiers, different languages and customs, etc. But these differences are not such that prevent the occurrence of trade between nations. He, therefore, asserts that general theory of value which can be applied to explain interregional trade can also be applied equally well to explain international trade.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to general equilibrium theory of value, relative prices of commodious are determined by demand for and supply of them. In the long-run equilibrium under conditions of perfect competition, relative prices of commodities, as determined by demand and supply, are equal to average cost of production.

The cost of production of a commodity, as is well-known, depends upon the prices paid for the factors of production employed in the production of that commodity. Factor prices in turn determine the incomes of the factor owners and hence the demand for goods.

Thus trade is mutual inter-dependence between prices of commodities and prices of factors, and the exchange of goods and factors between demand for commodities and demand for factors. This is how general equilibrium theory of value explains prices of commodities and factors between different individuals in a region or a country.

However, according to Ohlin, the classical analysis presumes it to apply to a single market in a country and ignores the space factor whose introduction is crucial for explanation of trade between regions. The factors which explain the trade between different regions also explain the trade between different nations or countries as well.

Heckscher-Ohlin Theorem:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

According to Ricardo and other classical economists, international trade is based on differences in comparative costs. It is important to note that Heckscher and Ohlin agreed with this fundamental proposition and only elaborated this by explaining the factors which cause differences in comparative costs of commodities between different regions or countries. Ricardo and others who followed him explained differences in comparative costs as arising from differences in skill and efficiency of labour alone.

This is not a satisfactory explanation of differences in comparative cots. Ohlin pointed out more significant factors, namely, differences in factor endowments of the nations and difference in factor proportions of producing different commodities, which account for differences in comparative costs and hence from the ultimate basis of inter-regional or international trade.

Thus, Heckscher-Ohlin theory does not contradict and supplant the comparative cost theory but supplements it by offering sufficiently satisfactory explanation of what causes differences in comparative costs.

According to Ohlin, the underlying forces behind differences in comparative costs are twofold:

1. The different regions or countries have different factor endowments.

2. The different goods require different factor-proportions for their production.

It is a well-known fact that various countries (regions) are differently endowed with productive factors required for production of goods. Some countries posses relatively more capital, some relatively more labour, and some relatively more land.

The factor which is relatively abundant in a country will tend to have a lower price and the factor which is relatively scarce will tend to have a higher price. Thus, according to Ohlin, factor endowments and factor prices are intimately associated with each other.

Suppose K stands for the availability or supply of capital in a country, L for that of labour and PK for price of capital and PL for the price of labour. Further, take two countries A and B; in country A capital is relatively abundant and labour is relatively scarce. The reverse is the case in country B. Given these factor-endowments, in country A capital will be relatively cheaper.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In symbolic terms:

Since (K/L)A > (K/L)B

Since (PK/PL)A < (PK/PL)B

Thus the differences in factor endowments cause differences in factor prices and therefore account for differences in comparative costs of producing different commodities. Together with the difference in factor-endowments, differences in factor proportions required for the production of different commodities also constitute an important force underlying differences in comparative costs as between different countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Some commodities are such that their production requires relatively more capital than other factors; they are therefore called capital- intensive commodities. Still other commodities require relatively more land than capital and labour and are therefore called land-intensive commodities.

These differences in factor-productions (or what is also called differences in factor-intensities) needed for the production of different commodities account for differences in comparative costs of producing different commodities. The differences in comparative costs of producing different commodities lead to the differences in market prices of different commodities in different countries.

It follows from above that some countries have a comparative advantage in the production of a commodity for which the required factors are found in abundance and comparative disadvantage in the production of a commodity for which the required factors are not available in sufficient quantities.

Thus a country A which has a relative abundance of capital and relative scarcity of labour will have a comparative advantage in specialising in the production of capital-intensive commodities and in return will import labour-intensive goods. This is because (PK/PL)A < (PK/PL)B.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

On the other hand, a labour-abundant country B with a scarcity of capital will have a comparative advantage in specialising in the production of labour-intensive commodities and export some quantities of them and in exchange for import capital-intensive commodities. This is because in this country (PL/PK)B < (PL/PK)A.

If factor endowments in the two countries are the same and factor-productions used in the production of different commodities do not differ, there will be no differences in relative factor prices [i.e. (PK/PL)A < (PK/PL)B] which will mean differences in comparative costs of producing commodities in the two countries will be non-existent. In this situation the countries will not gain from entering into trade with each other.

Let us graphically explain the Heckscher-Ohlin theory of international trade. Take two countries U.S.A. and India. Assume that there is a relative abundance of capital and scarcity of labour in U.S.A. and, on the contrary, there is a relative abundance of labour and scarcity of capital in India. (This is the real situation as well).

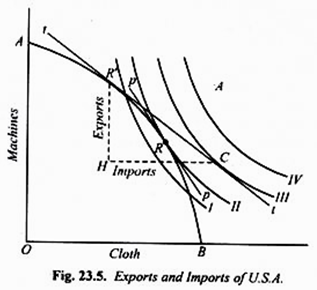

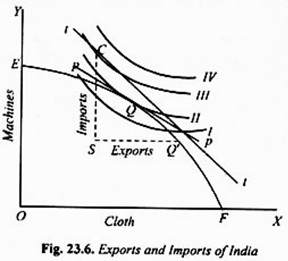

Given these factor endowments we have drawn the production possibility curves (also known as transformation curves) between two commodities, cloth and machines of the two countries, U.S.A. and India in Fig. 23.5 and 23.6 respectively.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Since the two countries have different factor endowments their production possibility curves will differ. As will be seen from Fig. 23.5, the production possibility curve AB of U.S.A. shows that given its factor endowments, U.S.A. can produce relatively more of capital-intensive commodity machines and relatively less of labour-intensive commodity cloth.

On the contrary, as will be seen from Fig. 23.6 with given factor endowments, India can produce relatively more of labour-intensive commodity cloth and relatively less of capital-intensive commodity machines.

In the absence of foreign trade, equilibrium in each country would be determined by the following rule:

MRTMC = MRSMC = PM/PC

Where MRSMC stands for a marginal rate of transformation of machines into cloth, MRSMC for marginal rate of substitution of machines for cloth and PM/PC for the price ratio between the two commodities.

In the geometric terms, the above rule implies that in the absence of foreign trade the production and consumption in the two countries would take place at the tangency point of the given production possibility curve with the highest possible community indifference curve.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It will be observed from Figure 23.5 that in the absence of trade, U.S.A. will be in equilibrium position with production and consumption at point R where its production possibility curve AB is tangent to its community indifference curve II.

The tangent pp to the production possibility curve AB and the community indifference curve II at point R indicates the ratio of price of the two commodities (i.e. the domestic rate of exchange) before trade in U.S.A.

As regards India, as shown in Figure 23.6 before trade, she will be in equilibrium with production and consumption at point Q at which its production possibility curve is tangent to its community indifference curve II. Tangent pp at point Q to its production possibility curve EF and the community indifference curve II shows the domestic rate of exchange of two commodities before foreign trade.

It will be seen from Figures 23.5 and 23.6 that the price ratio (rate of exchange) of the two commodities in the two countries differs (slopes of tangents pp in them vary). It will therefore pay the two countries to enter into trade with each other. Suppose, the terms of trade, that is, the ratio of exchange of goods between the two countries is given by the line tt.

It will be observed that with terms of trade line tt, U.S.A. will be in equilibrium from the view point of production at point R’ at which the terms of trade line tt is tangent to its production possibility curve AB. However, its consumption point after trade is C which is determined by the tangency of the terms of trade line tt with the community indifference curve III.

It will be seen from Figure 23.5 that in U.S.A. the consumption point C after trade lies at a higher indifference curve than before trade indicating the gain from trade it obtains. The consumption point C of U.S.A. as compared to its production point R’ after trade reveals that U.S.A. produces HR’ more of machines and HC less of cloth than it consumes domestically. Thus U.S.A. will export HR’ of machines and import HC of cloth.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

As regards India, it is evident from Figure 23.6 that as a result of trade its production point will shift to point Q’ where its product possibility curve EF is tangent to the terms of trade line tt. After trade, consumption in India will take place at point C at which the terms of trade line tt is tangent to its community indifference curve III.

As a result of trade India has also gained as she has reached a higher community indifference curve. Thus after trade with the production point Q’ and consumption point C, India will produce SQ’ more of cloth and SC less of machines than it consumes at home. Thus India will export SQ’ of cloth and import SC of machines.

It follows from above that due to differences in factor endowments in U.S.A. and India also and due to different factor proportions required for the production of different commodities the basis for trade between the two countries exists and both would gain from trade by specialising in the production of commodities which require factors in respect of which they are well endowed and will import those commodities which need factors which are relatively in scarce supply.

Critical Evaluation of Heckscher-Ohlin Theory of International Trade:

Heckscher and Ohlin theory has made invaluable contributions to the explanation of international trade. Though this theory accepts comparative costs as the basis of international trade, it makes several improvements in the classical comparative cost theory.

First, it rescued the theory of international trade from the grip of labour theory of value and based it on the general equilibrium theory of value according to which both demand and supply conditions determine the prices of goods and factors.

Second, Heckscher-Ohlin theory removes the difference between international trade and inter-regional trade, for the factors determining the two are the same. Third, a significant improvement is the explanation offered for difference in comparative costs of commodities between trading countries.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Ricardo thought that the differences in labour efficiency alone accounted for the differences in comparative costs. According to Heckscher and Ohlin, as seen above, the differences in factor-endowments of the countries and also the differences in factor proportions required for producing various commodities explain differences in comparative costs and hence from the ultimate basis of international trade.

These reasons advanced by Heckscher and Ohlin for differences in comparative costs of commodities in different countries are considered to be broadly true.

Fourth, as has been pointed out by Prof. Lancaster, Heckscher-Ohlin model provides a satisfactory picture of the future of foreign trade. According to the Ricardian theory, international trade exists because of differences in skill and efficiency of labour alone.

This implies that as there is transmission of knowledge between the countries so that they master the techniques and skills of each other, then differences in comparative costs would cease to exist and as a result international trade would come to an end. But this is not likely to occur despite the fact that transmission of knowledge and techniques has greatly increased these days.

Heckscher and Ohlin explain that international trade is due to the differences in factor-endowments (i.e. differences in supplies of all factors and not only of labour efficiency) and different factor-proportions required for different commodities. Since the factors such as land and other natural resources lack mobility, international trade would not cease to exist even if there is perfect transmission of knowledge between the countries.

Despite the above merits of Heckscher-Ohlin theory, it has some shortcomings which are briefly discussed below:

1. Leontief Paradox:

In the Heckscher-Ohlin theory it has been assumed that relative factor prices reflect the relative supplies of factors. That is, a factor which is found in abundance in a country will have a lower price and vice versa. This means that in the determination of factor-prices supply outweighs demand.

But if demand for factors prevails over supply, then factor prices so determined would not conform to the supplies of factors. Thus, if in a country there is abundance of capital and scarcity of labour in physical terms but there is relatively much greater demand for capital, then the price of capital would be relatively higher to that of labour.

Then, under these circumstances, contrary to its factor-endowments, the country many export labour-intensive goods and import capital-intensive goods. Perhaps it is this which lies behind the empirical findings by Leontief that though America is a capital abundant and labour-scarce country, in the structure of its imports capital-intensive goods are relatively greater whereas in the structure of its exports labour- intensive goods are relatively greater. As this is contrary to the popularly held view, this is known as Leontief Paradox.

2. Difference in Preferences or Demands for Goods:

Against Hecksher-Ohlin theorem, it has also been pointed out that differences in tastes and preferences for goods or, to put it in other words, differences in pattern of demand also give rise to trade between the countries. This is because under differences in demand or preferences for goods, the commodity price-ratios would not conform to the cost-ratios based on factor endowments.

Let us take an extreme example. Suppose there are two countries A and B with same factor-endowments. According to Heckscher-Ohlin theorem, with same factor endowments cost-ratio of producing the two commodities and hence the commodity price ratio would be the same.

Hence there is no possibility of trade between the two countries on the basis of Heckscher-Ohlin theorem. However, trade between the two countries is possible if the demand pattern or preferences of the people of the two countries for wheat and rice greatly differ.