In this essay we will discuss about Wages in Economics. After reading this essay you will learn about: 1. Meaning of Wages 2. Types of Wages 3. Theories of Wages 4. Modern Theory of Wages 5. Union and Wages – Collective Bargaining 6. Wage Differentials 7. Minimum Wages 8. Benefits of Minimum Wages 9. Adverse Effects of Minimum Wages.

Contents:

- Essay on the Meaning of Wages

- Essay on the Types of Wages

- Essay on the Theories of Wages

- Essay on the Modern Theory of Wages

- Essay on Union and Wages – Collective Bargaining

- Essay on Wage Differentials

- Essay on Minimum Wages

- Essay on Benefits of Minimum Wages

- Essay on Adverse Effects of Minimum Wages

Essay # 1. Meaning of Wages:

Wages are a payment for the services of labour, whether mental or physical. Though in ordinary language an office executive, a minister or a teacher is said to receive a salary; a lawyer or a doctor a fee; and a skilled or unskilled worker a wage, yet in economics no such distinctions are made for different services and all of them are said to receive a wage.

In other words, wages include fees, commissions and salaries. It is another thing that some may be receiving more in the form of real wages and less in terms of money wages and vice versa. We shall refer to this problem later on.

Essay # 2. Types of Wages:

(i) Time and Piece Wages:

Wages may be paid weekly, fortnightly, or monthly and partly at the end of the year in the form of bonus. These are time wages. But the bonus may be a task wage if a work is finished within a specified period or before that.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Sometimes, time wages are supplemented by wages earned by working extra time. They are over-time wages. Wages are also paid in accordance with the amount of work done, say in a shoe factory or a tailoring department as per one pair of shoes or pants manufactured.

If the rate per pair of shoes or for pants is Rs 50, a worker will be paid according to the number of pairs of shoes or pants manufactured. These will be piece wages.

(ii) Money Wages and Real Wages:

Money wages or nominal wages relate to the amount of money income received by workers for their services in production. Real wages include the various facilities, benefits and comforts which workers receive in terms of goods and services for their work. These are in addition to the money wages of workers.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Real wages depend upon the following factors.

a. Price Level:

The purchasing power of money depends upon the price level. When the price level rises, the purchasing power of money gets reduced, thus adversely affecting the real wages of workers. Every increase in the price level reduces the purchasing power of money. This leads to a fall in the real wages of workers.

b. Money wages:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The size of the pay packet received by the worker is an important determinant of his real wages. The greater the money wages, the greater will be the real wages, other things remaining the same.

c. Regularity of Work:

A permanent job, even though it carries a smaller money income, is considered to be better than a temporary job which may yield high reward in terms of money.

d. Nature of Work:

The nature of work also plays an important role in determining the level of real wages. Some jobs are pleasant, while others are not. Similarly, some occupations are enjoyable while others are disagreeable. All these considerations have to be given weightage in determining real wages.

e. Future Prospects:

An occupation carrying the promise of better prospects of promotion in the future is considered to be better than the one which does not do so, even though the money wages offered by the latter may be high.

f. Extra Benefits:

In some occupations, employees receive in addition to their pay, some extra benefits. For example, the manager of a firm gets in addition to his pay, a well furnished bungalow, free medical help etc. Such benefits increase the real wage of a worker.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

g. Trade Expenses:

This refers to the expenses one has to incur in the course of one’s occupation. These expenses are high in some occupations while in others they may be moderate. These expenses should be deducted from the money income in order to arrive at the real wage.

h. Social Prestige:

The real wages of employees engaged in prestigious occupations are high as compared to the real wages of employees working in ordinary occupations.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

i. Form of Payment:

Real wages are influenced by the form of payment. Generally, workers are paid money wages. But in certain occupations, in addition to money wages, workers receive subsidized ration or free lunch, and living quarters. All these facilities increase the real wages of workers.

j. Conditions of Work:

Conditions of work also affect real wages. In some cases, it is found that conditions of work are not congenial and they adversely affect their health. In such cases, the real wages of workers are low.

Essay # 3. Theories of Wages:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Different theories have been put forward from time to time to explain as to how wages are determined. The main elements of these theories are explained below.

(i) The Subsistence Theory of Wages:

The subsistence theory of wages was first formulated by the Physiocratic School of French Economists of 18th century. The theory was further developed and improved upon by German economists who called it as the Iron Law of Wages.

According to this theory, labour power is a commodity and its price is determined by its cost of production. Its cost of production is the minimum subsistence expenses required for the support of the worker and his family so that continuous supply of labour is maintained. The exponents of this theory held that wages have a tendency to settle only at the subsistence level or cost of production.

If at any time, wages exceeded this level, workers finding themselves in better economic position, would marry. As such, population would increase and with it the supply of labour. This tendency would continue to operate until wages were reduced to the minimum subsistence level.

If, on the other hand, wages fell below the subsistence level, there would be reduction in population through starvation or diseases among workers, thereby bringing about a shortage in the supply of labour. This tendency would continue to operate until wages were again raised to the minimum subsistence level.

Thus the subsistence theory of wages reaches the neither conclusion that the wage level can neither rise nor fall below the minimum subsistence level.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Its Criticisms:

This theory has been criticised on the following grounds:

a. Wrongly based on the Malthusian Theory of Population:

The subsistence theory of wages is based on the Malthusian theory of population which, in turn, is a highly controversial theory and never has its applications in Western economies.

b. Historically not correct:

Critics also maintain that historically this theory has not been correct in its conclusions. Experience shows that a rise in wages is not necessarily accompanied by an increase in population; rather it is followed by a decline in the rate of growth of population.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

c. Unable to Explain Difference in Wages:

Labour market is characterised by heterogeneity of wage rates. If wage rates were to be equal to the subsistence level, then they would have been uniform for everyone. This is also a proof that the theory is unrealistic.

d. One-sided Theory:

This theory approaches the problem of wage determination from the side of supply and completely ignores the demand side of labour. This theory is thus one sided.

e. Highly Pessimistic:

This theory is highly pessimistic for the working class. It presents a very dark picture of the future of the society.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

f. No attention to Efficiency and Productivity:

According to this theory, wage rate for all workers tends to be equal to the minimum subsistence level. But it need not be so because workers differ in efficiency and productivity. The discussion given above shows that the subsistence theory of wages is not a sound doctrine as it fails to present a correct empirical description of the actual facts in the labour market.

(ii) The Standard of Living Theory of Wages:

The pro-pounders of this theory were some classical economists of the late 19th century who presented a modified version of the subsistence theory of wages. The standard of living theory of wages states that in the long-run wages tend, to equal the standard of living of workers. There is some standard of living to which workers are habituated. They will try to maintain it, with no tendency to increase or decrease it.

Although this level is determined primarily by physical or biological requirements, it is also determined by social and customary needs which, in turn, influence the rearing of children. If wages fall below the established standard of living of workers, they will stop having children.

As a result, population will decline. The supply of labour will be reduced, its marginal productivity will increase and wages will rise. Conversely, if wages rise above the standard of living, workers will tend to have more children. Population will increase. The supply of labour will rise, its marginal productivity will decline and wages will fall.

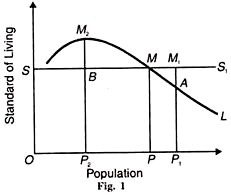

This theory is explained in Figure 1 where population is measured along the horizontal axis and standard of living on the vertical axis. Suppose the line SS1 is the standard-of-living level of workers and L is the actual level of living curve.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At OP level of population, the workers are maintaining PM (=OS) standard of living. If the population rises to OP, level, the actual level-of-living curve will be below the standard of living curve SS1 as shown by the distance AM1 As a result, the workers will stop having children.

The population and supply of labour will decline and wages will rise. The standard of living of workers will again equal level-of-living curve at point M. On the other hand, if the population falls to OP2 level, the actual level-of-living curve L will be above the SS1 curve, as shown by the distance BM2.

Consequently, the workers will have more children. The population and supply of labour will increase and wages will fall. The standard of living of workers will again equal their actual level-of-living curve at point M. Thus wages tend to equal the standard to living of workers in the long-run.

Its Criticism:

This theory is better than the subsistence theory of wages because it takes into account efficiency and productivity of workers. Despite this, it is not free from pertain criticisms.

a. Interdependent:

The theory states that the standard of living determines wages. But standard of living is also determined by wages. The standard of living of a worker depends upon the wages he receives. Thus the standard of living and wages are interdependent.

b. Standard of Living not fixed:

The theory assumes that the standard of living of workers is fixed, as shown by the horizontal line SS, in Figure 1. In reality’ standard of living rises when the wages of workers increase.

c. Fails to Explain Wage Differentials:

This theory is based on the assumption that wages tend to equal the standard of living of workers. This means that all workers receive uniform wages. But workers in different categories and occupations receive different wages. Thus the theory fails to explain wage differentials.

d. No Direct Relation between Wages and Population:

The theory assumes that wages and population are directly related. This is a wrong assumption. The experience of advanced countries shows that the rise in wages is not accompanied by an increase in population but by a decline in population via the increase in standard of living.

e. Ignores the Demand for Labour:

This theory explains the determination of wages from the supply side and ignores the demand side of labour. Thus this theory is a one-sided theory.

(iii) The Wage Fund Theory:

The wage-fund theory was propounded by J.S. Mill. According to this theory, “Wages depend upon the proportion between population and capital, or rather between the number of the labouring class who work for hire and the aggregate of that may be called wage-fund”.

The theory says that wages are determined by two factors:

(1) Wage Fund:

It is that amount of capital which is set apart by the entrepreneurs for the direct purchase of the services of labour.

(2) Population:

It refers to that section of population which enters the labour market for employment. The total wage-fund available for distribution among labourers is a fixed sum, the result of past saving or accumulation. Wages depend upon the proportion or ratio between circulating capital or wage-fund and population. The theory can be stated in the form of the following equation:

AW = Wage Fund/Population[AW Average Wage]

This equation shows that wages can increase either when wage-fund increases or when population decreases. The wage-fund, argues Mill, can be increased by saving which is not under the control of workers. So, if they want an improvement in their wage level, they should reduce the numbers.

Its Criticisms:

This theory has been widely criticised on the following grounds:

a. Unscientific:

Critics maintain that this theory rests upon the unscientific idea of a fixed fund. National income is a flow and not a fund. Wages are paid out of national income and not out of a fixed fund set apart by entrepreneurs for the purchase of the services of labour.

b. No Conflict between Wages and Profits:

The theory contends that there is a conflict between wages and profits. Mill maintained that an increase in wages will necessarily bring down profits. However, this may not happen. For example, during inflationary conditions, both profits and wages increase. Thus, the wage fund theory does not hold well in real life.

c. Differences in Wages:

This theory cannot explain the existence of wage differentials among workers. This weakness makes the theory highly unrealistic. Critics maintain that if the wage fund is fixed and the wage rate depends upon the number of workers seeking employment, then it follows that the wage rate throughout the country must be uniform. But in actual life, this is not the case.

d. Labour is not Homogeneous:

The theory rests upon the assumption that labour is homogeneous. But this assumption is not in conformity with the facts of life. Workers differ in efficiency and productivity. In fact, labour is highly heterogeneous.

e. Ignores the Influence of Trade Unions:

In modern times, trade unions are able to affect a rise in the wage level. But the wage-fund theory is incompetent to explain this phenomenon.

f. Nature of Fixed Fund:

The theory is based upon the idea of a fixed fund. Critics point out that there does not exist anything like a fixed fund. Even if it exists in the mind of entrepreneur, it is subject to variations. It cannot remain fixed for ever. It can increase or decrease in accordance with the requirements for it.

g. Ignores Productivity:

A main defect of the theory is that it completely ignores the effect of productivity on wages. Critics point out that the wage-fund comes from labour. Wages are no doubt drawn out of a reservoir of capital but this reservoir is constantly fed by the products of labour.

The higher the efficiency, the higher will be the wages. But the wage fund theory does take note of this fact. Mill himself realized its weaknesses. Bowing down to the critics, he withdrew this in the second edition of his Principles.

(iv) The Residual Claimant Theory:

The residual claimant theory of wages was propounded by an American economist Francis A. Walker who stated that “the wages of labourers are paid out of the product of his industry.” This theory maintains that wages equal the whole product minus rent, interest and profits. In other words, the theory holds that wages are equal to the product of the industry minus deductions for the other three factors of production.

The theory regards workers as the residual claimant of the product of the industry. In the words of Jevons, “The wages of the working man are ultimately coincident with what he produces after the deduction of rent, taxes and the interest on capital.”

The bright aspect of the theory is that if labour puts in more efforts to increase production without increasing the input of other factors, the residual amount which labour claims in the form of wages gets enhanced. In other words, we may say that the theory recognizes labour claim to that portion of national income which is the result of its greater efficiency and productivity.

Its Criticism:

The residual claimant theory of wages has been criticised on the following grounds:

a. Entrepreneur is the Residual Claimant:

The theory does not explain why labour should be the residual claimant to the product of the industry. In reality, it is the entrepreneur and not the worker who is the residual claimant.

b. No Need for a Separate Theory:

Critics maintain that factor prices are determined by the forces of demand and supply and there appears to be no need for a separate theory of wages.

c. Ignores Trade Unions:

If wages are a residual, then the progressive increase in wages by trade union action is totally ignored.

d. One-sided Theory:

This theory is also one-sided as it approaches the problem from the side of demand. The supply side has been completely ignored.

e. Determination of Rent, Interest and Profits:

A major weakness of the residual claimant theory is “its lack of a positive method of determining what the level of rent, interest and profits should be.”

Conclusion:

Nevertheless, the residual claimant theory of wages served a useful purpose in emphasizing the significance of efficiency of labour. Labour, by increased efficiency can claim a greater share of the national income. “To some extent, this theory was a precursor of the current marginal productivity theory which relates wages to the productivity of the worker.”

5. The Marginal Productivity Theory of Wages:

The marginal productivity theory of wages is just an application of the marginal productivity theory of distribution.

According to this theory, wages in a competitive market tend to be equal to the marginal product of labour. Marginal productivity is an addition to total productivity resulting from the employment of an additional unit of labour. In a monetized economic system, an entrepreneur is interested not in the marginal physical productivity of labour but in the addition to the size of his total revenue.

An entrepreneur while making a decision regarding the employment of an additional hand takes into account marginal revenue productivity which, in turn, equals marginal physical product plus the price of the product. (Marginal revenue productivity = Marginal physical productivity +Price of the product).

The theory asserts that no worker under conditions of perfect competition can expect to receive wages greater than the value of marginal product, that is, marginal revenue productivity.

For example, if an entrepreneur hires workers at Rs 100 per day to produce goods that are sold for more than Rs 100, he would make a profit by hiring them. The entrepreneur in question would go on hiring additional units of labour till the point of equality between the marginal revenue product and the prevailing wage level is attained.

If, on the other hand, the entrepreneur hires workers at Rs 100 per day to produce goods which are sold for less than Rs 100, he would incur losses.

It follows that the entrepreneur will not pay wages to labour more than the value of his marginal product. If the entrepreneur is employing less labour, he can increase his profits by employing more labour, On the other hand, if he is employing more labour, he can increase his profits by reducing the employment of labour depending upon the position of the wage rate and the marginal revenue productivity.

Thus, the entrepreneur’s profits would be maximum or losses would be minimum at a point where the prevailing wage rate equals the marginal revenue productivity.

Essay # 4. The Modern Theory of Wages:

The wage rate, like any price, is determined by the demand for and supply of labour. Assuming perfect competition and absence of trade unions, what forces determine the demand for and supply of labour.

Assumptions:

This theory is based on the following assumptions:

(i) There is freedom of occupation. Any employer can employ any worker and any worker can work with any employer.

(ii) There are many workers and employers in the labour market and no single worker or employer can influence the wage rate.

(iii) There is perfect mobility of workers in different employments.

(iv) There is full employment of labour. Vacant jobs are filled at the same time.

(v) Workers and employers have perfect knowledge of labour market. Workers know where vacant jobs exist and what the wage rates are. Employers know about workers as to where they are available and at what wage rate.

Demand for Labour:

Labour is demanded for its service by the employers in helping to produce goods. Thus the demand for labour is derived from the demand for the goods it helps to produce, if a rise or fall is expected in the demand for a product, it will lead to a rise or fall in the demand for the labour which produces the product.

In fact, it is not the demand for labour that matters but the elasticity of demand for labour which depends on the elasticity of demand for its product. The more elastic is the demand for the product, the more elastic is the demand for the labour which makes the product.

The elasticity of demand for labour is the percentage increase in the number of workers employed as the wage rate falls by 1%. But this does not mean that the percentage increase in employment will be in the same proportion as the fall in the wage rate; the increase in employment may be greater.

In case, however, a small amount of labour is engaged in the production of a product, the demand for that type of labour is inelastic. In factories using automatic machines, highly skilled labour of a particular type is employed in very limited quantity and it is not possible to find this type of labour easily.

The demand for such a type of labour is inelastic. Lastly, the elasticity of demand for labour depends on the degree of substitution between labour and other factor-services. The cheaper and better the substitutes for labour, the more elastic is the demand the labour.

If machines are cheap and easily available, they can be substituted for labour. A rise in the wage rate will encourage the use of more machines for labour. Conversely, a fall in the wage rate will lead to the employment of more labour in place of at least worn out machines.

In case the cost of machines is very high or a particular type of labour is indispensable (that is, has no substitute), a rise in its wages will not decrease its demand. The demand for this type of labour is elastic. Specifically, labour is demanded because of its productivity.

What a unit of labour adds to the total revenue of the firm is its marginal revenue productivity. The wage rate at any time is equal to the marginal revenue productivity.

So long as the marginal revenue product of labour is more than the wage rate, it is profitable to employ more labour for it adds more to revenue than to cost. But the employment of more labour tends to diminish the marginal revenue product of labour, after a point, based as it is on the law of variable proportions.

That is why the demand curve for labour slopes downward from left to right and is shown as the marginal revenue productivity curve (MRP). It is the demand curve for labour at each level of employment. It also shows the amount of labour the firm would employ at each possible wage rate.

Supply of Labour:

The supply of labour means the number of workers that would offer themselves for employment at each possible wage rate. The relationship between wages and the quantity of labour is a direct one. Usually a greater quantity of labour is offered at rising wage levels.

That is why, the supply curve of labour slopes upwards from left to right. An industry will be faced with such a supply curve. It can only attract more labour by offering high wages.

The supply of labour, however, depends on a number of factors like the rate of population growth, the age and sex of distribution of population, the working hours, the normal period of education and training, labour laws regarding the employment of child and woman labour, the attitude of society towards the employment of woman labour, the attitude of labour in general towards work and leisure, the mobility of labour.

Taking the last factor first, it is the mobility of labour which determines the elasticity of the supply of labour. If the labour is mobile, its supply will be elastic. A small rise in the wage rate of this type of labour will attract a large number of workers from other occupations, and a small fall in the wage rate will lead to an outflow of workers to the other occupations.

If labour is less mobile between occupations for it requires exceptional skill and ability, its supply will be inelastic. For neither a rise nor a fall in wages can attract in or drive workers out of occupation. In any case, the shorter the period, the less elastic is the supply curve of labour, and the longer the period, the more elastic it is.

Backward Sloping Supply Curve of Labour:

Another important factor in the supply of labour is the work-leisure ratio. At low level of wages, workers will work for longer hours. But with the rise in the wage rate, the workers take home bigger pay-packets and a time comes in the life of each worker, when he feels that at a particular wage rate his needs are easily met. If the wage rate rises above this level, he would prefer to work for lesser hours and enjoy leisure instead.

In this case, the supply curve of labour is “backward-sloping”. Two trends are noticeable in this attitude of workers as the wage rate rises; each labour-hour becomes more paying and the worker substitutes work for leisure. Rise in the wage rate induces workers to work more and take less leisure. Secondly, there is the income effect.

As the wage rate rises substantially, workers feel better-off than before and they are inclined to enjoy more leisure.

The former effect reduces the desire for leisure and the latter increases it. In the initial stages, the substitution effect becomes more powerful as the wage rate rises, but when the wage rate rises beyond a point, the income effect becomes more powerful.

This is because the desire for extra recreation becomes stronger as income increases and this makes the income effect more powerful and the desire for additional income becomes less intense and this reduces the strength of the substitution effect.

All this takes place gradually and the supply curve also slopes backward gently. Such a curve may exist both in the case of the individual worker and for the economy. But there is a difference in the two cases. The supply curve of labour for the individual worker slopes backward only when the number of workers in an occupation cannot change.

It happens in the short-run. But in the case of the economy, the supply curve of labour tends to bend backward more in the long-run than in the short-run. No doubt, population increases in the long-run but the majority of the workers in the developed countries are influenced by the income effect as the national average wage rate continues to rise.’ In the analysis that follows, we take the usual supply curve.

Its Determination:

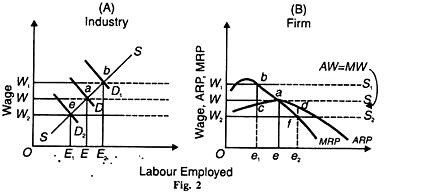

The wage rate in an industry will be determined at a point where the demand for labour equals the supply of labour. In Figure 2 (A), OE workers are employed at OW wage rate. There cannot be any deviation from this equilibrium position. A wage rate above equilibrium level to say, OW1 will induce more workers to offer themselves for employment and the firms would be induced to cut down employment.

Thus wages will be brought down to OW level. Contrariwise, a fall in the wage level to OW, would lead to the exodus of workers from the industry and the firms in a bid to stop this, would offer higher” wages and the equilibrium level of wages would be restored.

In case, however, the demand for labour increases or decreases on the part of the industry to D to D2 the wage rate would rise or fall to OW1 to OW2 accordingly, but only in the short-run. In the long-run, equilibrium will ultimately be restored at the wage rate of OW.

For all firms under perfect competition, the wage rate is given at any time, as determined by the industry demand and supply curves of labour. The supply curve of labour for the firm (WS) is, thus, perfectly elastic at the current wage rate, as shown in Panel (B). The equilibrium point for the firm is where the marginal revenue productivity curves; MRP cuts the horizontal supply curve of labour, WS.

In other words, it is a point where the cost of employing labour (the wage rate) equals the marginal revenue product of the labour to the employer. For full equilibrium, it is essential that marginal revenue product of labour should equal its marginal cost (marginal wage) and the average revenue product be equal to the average cost of labour (average wage).

AW = MW

... and MRP = MW

ARP = AW

... MRP = MW = AW = ARP

In Panel (В) Point a is of full equilibrium, where Oe number of workers are employed. A firm will be earning profits fd per unit of labour by employing Oe2 workers when the wage rate W2S2 is below the ARP curve. It will be sustaining losses cb per unit of labour by employing Oe1 workers, if the wage rate W1 S1 is above the ARP curve. It will be earning normal profits when the wage rate is WS. A firm can afford to remain under conditions of profit or loss only in the short-run.

In the long-run, in the case of loss when the wage rate is W1S1 some firms will leave the industry, the demand for labour will fall and the wage rate will come down to WS where it equals the ARP curve at point a. In the opposite case when the wage rate is W2S2, attracted by the profits some new firms will enter the industry and the old ones will have a tendency to expand.

The demand for labour would rise and thus push up the wage rate to WS where it equals the ARP curve at point a. Thus the wage rate under perfect competition is always equal to the marginal and the average revenue product of labour: AW = MW = MRP = ARP.

Essay # 5. Union and Wages – Collective Bargaining:

The main function of a trade union is to raise wages and to improve the working conditions of its members. It replaces individual bargaining by collective bargaining and makes the rates of wages uniform for the same category of workers over the entire industry.

Under perfectly competitive labour market, wages in a particular industry are fixed by the forces of demand and supply. But unions can raise wages in the short-run by reducing the supply of labour.

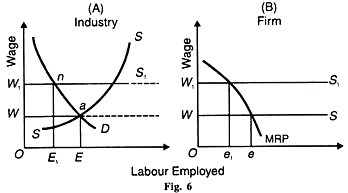

This is illustrated in Panels (A) and (B) of Figure 6. Panel (A) shows the equilibrium wages rate OW being determined by the equality of demand and supply of labour OE at point a. in Panel (B), at a given wage rate OW or WS the firm employs Oe units of this labour.

If the workers employed in this industry form a union, they cannot affect the demand for labour in the short-run. They may demand a wage rate above the equilibrium rate OW but it will tend to reduce the number of workers employed.

Suppose the union asks for OW1 wage rate. This will tend to make the supply curve of labour perfectly elastic so that it now becomes W1S1 in place of SS in Panel (A).

The new equilibrium position is established at n where the demand curve D intersects the supply curve W1S1 and the number of workers employed in the industry is reduced from OE to OE1 The given wage rate for the firm being W1S1 it will also employ less workers than before, Oe1 < Oe as shown in Figure 6 (B).

If the union wishes to maintain the increased wage rate, it will have to reduce the supply of labour, It may do so in a variety of ways: by encouraging the unemployed to seek jobs in other industries; by raising the membership fee for new entrants; by raising the apprenticeship period and by encouraging restrictions on immigration, etc.

Above all, the reduction in supply will depend upon the elasticity of demand for labour. If the demand for labour is quite inelastic, then the reduction in supply would be small. But this is not likely to be the normal situation in the case of an industry.

If somehow the union is able to shift the MRP curve (demand curve for labour) upward to the right, the wage rate would be raised substantially and the employment would also expand. But to raise the demand for labour is not an easy job for the unions. This is possible over the long-run when technological changes raise the demand for the industry’s product.

The union can then demand a wage increase, the rise being negotiated by collective bargaining. Marshall has conceived of certain situations when the union of a particular group of workers can raise the wages of its members by threatening to withdraw their supply.

It is possible if:

(i) The demand for the services of that set of workers is inelastic; or

(ii) The demand for the commodity which the group helps to produce is inelastic; or

(iii) The wage-bill of this group forms a very small proportion of the total wage-bill of the concern so that a rise in their wages does not substantially affect the total cost of production of the commodity; and lastly, if the other cooperate factors are squeezable, that is, the wages of the other group of workers are reducible or the raw material suppliers are forced to accept low prices, etc.

The union will be successful if any of these conditions is fulfilled. This is only possible in the short-run. In the long-run, the employer may try for substitutes by adopting a device to replace this group of workers.

In a perfectly competitive labour market, wages are paid equal to the marginal revenue product of labour. But competition is not perfect and labour is paid much below the marginal revenue product. A trade union can raise wages up to the marginal revenue product level by collective bargaining.

A rise in the wage rate which equals the marginal revenue product of labour would neither affect employment nor output adversely. Assuming that the employers are not united a powerful trade union can force the industry to pay wages equal to the marginal revenue product. In such a situation, it is difficult to import even the ‘Black-legs’.

In the case of a monopolist buyer of the services of labour, the workers will be paid less than their marginal revenue product and even the number of workers employed will be much smaller than the under perfectly competitive labour market.

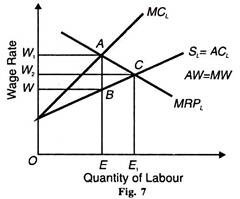

In Figure 7, OE quantity of labour is employed at OW wage rate by the monopolist, as against OE, quantity of labour at OW2 wage rate if there were perfect competition in the labour market.

If the workers are organized, their union through collective bargaining can raise the wage rate to OW2 and at the same time increase employment to OE1 up to the competitive market level C. But if the union tries to push up the wage rate above OW2 employment will fall.

If the union follows the ‘closed shop’ policy and does not bother about increasing the level of employment, it can at best raise the wage rate to OW1. But employment will be reduced from OE1 to OE. It means that the trade union has a monopoly in the selling of the services of labour and aims at destroying monopolist exploitation by asking for OW1 wage rate. This is the case of bilateral monopoly.

Essay # 6. Wage Differentials:

There are wide differences in wages received by individuals from occupation to occupation, from industry to industry, from district to district and from region to region within a country. International wage differences are, however, the greatest.

Why is it that a college lecturer with pleasant work, long vacations and interesting students receives more pay than a bus driver’s nerve-straining back-breaking and tiresome job? Why is it that an agricultural labourer recieves a lower wage per hour than a coal-miner, a factory worker at Cochin receives less than a worker in Chennei, and a worker at Faridabad gets a lower wage, than a worker at Mumbai? The causes of these various types of wage differentials are numerous.

A. Smith’s Reasons:

Assuming labour of the same efficiency and perfectly, mobile between occupations and places, Adam Smith assigned five reasons for wage differentials.

(1) “The agreeableness or the disagreeableness of the employments themselves” is the main cause of variations in wages. People are prepared to accept a low paid job which is pleasant and light as against a tiresome and dirty job which offers more pay.

(2) “The easiness and cheapness or the difficulty and expense of learning them.” Occupations which are easy and cheap to learn carry low wages as against those which are difficult, more expensive and take more time to learn. The wages for the services of lawyers, physicians and engineers are higher as compared with other occupations.

(3) “The constancy and inconstancy of employment in them. ”Jobs of a temporary nature carry higher wages than those which are permanent. A factory worker earns less per day as against a mason, for the latter gets work only for a part of the year.

(4) “The small or great trust which must be reposed in those who exercise them.” Persons in whom greater trust or responsibility is reposed are paid higher wages than the ordinary lot. That is why the wages of goldsmiths, jewelers and managers are very high.

(5) “The probability or improbability of success in them.” Smith pointed out that where success is uncertain, wages must be high. But despite the risk of failure involved in the legal profession, many persons are attracted into it, but their real earnings are low if we were to take into account the period involved in becoming successful.

The above causes of wage differentials, as given by Adam Smith, are applicable to a society where full employment exists. But in the world we live, there is neither full employment nor perfect mobility of labour. Labour is not homogeneous.

Men differ in efficiency and so do their wages. Actual wage differentials, thus, run counter to Adam Smith’s explanation: the janitor with the most unpleasant work is among the lowest paid members of the community and so is a casual labourer, to cite a few instances. In this world, where imperfect competition is the rule, the real causes of wage differences are to be found in the following factors.

B. Non-Competing Groups:

There are certain occupational groups in which the supply of labour is limited because all and sundry cannot enter them. It is not easy to pass from one group to another.

Prof. Taussig distinguished five distinct groups:

(i) The unskilled workers like ordinary labourers who carry earth, sand or bricks in construction work;

(ii) The semi-skilled workers like those who can mix sand and cement in the required proportions;

(iii) The skilled workers who require special training and skills, like the mechanic, the locomotive driver, the plumber;

(iv) The clerical workers who possess some minimum academic qualification; and

(v) the professional group such as the lawyer, the teacher, the physician, the actor and the manager.

There is limited competition among the first three groups. An unskilled worker can become semi-skilled within a few months and the semi-skilled can be a skilled worker by acquiring some education and training.

C. Non-Equalizing Differences:

But the real difficulty starts when we move to the fourth and fifth groups. Carpenters cannot enter the teaching profession. A clerk cannot become the manager of a concern. For movement from a lower group to a higher group requires exceptional ability long and costly education and training. Even within groups there are non-competing groups. An administrative officer cannot fill the post of a nuclear physicist.

The existence of non-competing groups is due to social stratification, family environment, differences in ability, financial position and opportunity. The son of a petty shopkeeper can become a surgeon or an engineer if he has the ability and enough money to support him during his academic career.

But such cases are rare. Generally, children belonging to workers in the first three groups have little chance of going up the ladder in the fourth and the fifth groups due to their family set-up.

D. Equalizing Differences:

Such wage differences exist among jobs for which people from the same group are eligible. Within each group some jobs are more pleasant and secure while others are strenuous and dangerous. Very few people are willing to enter the latter. So higher wages are paid to attract workers. In the pleasant job, there are many entrants and they are paid comparatively low wages.

A college lecturer earns less than a doctor. The higher earnings of the doctor compensate him for longer and often irregular hours of work and for the more expensive and strenuous period of training undergone as compared to the lecturer. Such wage differentials are ‘equalizing differences’ for they tend to equalize the non-monetary differences existing in the job belonging to the same group.

E. Geographical Differences:

There are the geographical wage differentials which are, in fact, due to industrial and occupational differences. In examining geographical wage differences, we are concerned with real wages and not with money wages.

Money wages are generally low in rural areas than in cities. But the living is also less costly there, so real wages may be the same in both areas. Besides the differences in the cost of living between rural and urban areas, there are other factors responsible for their wage differentials.

The ruralities are unskilled and unorganised workers whereas in the cities workers are mostly skilled and organised into trade unions. Moreover, the regular sources of labour supply of the cities are the ruralities who must be offered higher wages to attract them.

F. Market Imperfections:

The main cause of rural-urban and regional wage differentials lies in market imperfections. Inertia, family and familiar associations, attachment to land and property keep the worker tied down to one place.

The cost of movement, the fear of adjusting one’s self to new surroundings the fear that one may not be a success in the new occupation, the risk in surrendering seniority and chances of promotion in the existing occupation are some of the considerations, which make the workers reluctant to leave the present job.

Often workers are ignorant of better job opportunities. There are also discriminations on the basis of race, sex and age which hinder mobility of labour. Last but not the least, certain unions follow the closed-shop policy. This does not mean that wage differentials exist due to market imperfections.

Essay # 7. Minimum Wages:

Minimum wage is that wage which provides not only for the bare sustenance of life but also for the preservation of the efficiency of the worker. It is the minimum that must be paid to the worker to cover his and his family’s bare necessities, including some measure of education, medical and other amenities.

Prof. Dobb defines a minimum wages as “the standard rate which a trade union attempts to establish by collective bargaining.” The demand for the fixation of a minimum wage arose to forbid the payment of unduly low wages in ‘sweated trades’, i.e. trades in which work was done by hand for long hours and under unhealthy conditions.

Gradually, it has been extended to even non-sweated industries where labour is not properly organised and where wages are exceptionally low. These days a national minimum wage for all types of employments has been fixed by law.

Essay # 8. Benefits of Minimum Wages:

The following are the benefits from the fixation of minimum wages for workers.

a. Increase in National Income.

Fixing minimum wages are “unambiguously advantageous to the national dividend,” according to Prof. Pigou. Minimum wages will so increase the incomes of workers that their consumption expenditures will increase which will, in turn, lead to an expansion of the consumers’ goods industries and via acceleration principle to the capital goods industries. All this will tend to stimulate employment, output and national income.

b. For Industry:

Minimum wages prove beneficial both to the employers and the community by increasing the efficiency and productive capacity of the industry. Higher wages by raising the standard of living increase efficiency and even the bargaining power of the workers. Thus higher wages by raising productivity encourage employers to adopt better techniques of production and weed out the inefficient employees.

c. Industrial Peace:

Minimum wages, if related to the cost of living, as is the case in advanced countries, tend to reduce labour unrest and maintain industrial peace.

d. Remove Exploitation:

Minimum wages for sweated trades tend to remove exploitation of workers by employers. But there is the fear of unemployment if the workers do not have a strong trade union. The employers may recruit new workers and turn out the existing workers.

e. Profit Squeeze:

In industries where the demand for workers in inelastic, it is not possible for employers to turn out the workers when minimum wages are fixed. It will lead to profit-squeeze, i.e. reduction in profits. But the workers will receive higher wages.

f. Price Rise:

If, in the above situation, the employers are not prepared to cut down their profits, the burden of the minimum wage might be passed on to consumers by raising the prices of products.

g. Equitable Distribution:

In advanced countries where the unemployed are covered by unemployment relief, the workers will indirectly benefit from the imposition of minimum wages. When they become unemployed, they receive unemployment relief from the government. The money for this comes by taxing the relatively rich. This leads to more equitable income distribution.

Essay # 9. Adverse Effects of Minimum Wages:

But there is no guarantee that the fixation of a minimum wage may be beneficial for workers and the economy. There are likely to be the following adverse effects of minimum wages.

(i) On Unemployment:

The fixation of minimum wages is likely to lead to the unemployment of workers in many ways.

First, when minimum wages are fixed, the employers may dispense with the services of some workers who will become unemployed.

Second, if the employers are forced to pay minimum wages, they may install labour-saving machines and thus turn out some workers. This will depend on the elasticity of demand for the type of labour in question and for the product they manufacture.

Third, when the state fixes a minimum wage for all employments, it makes the supply curve of labour horizontal to an employer at that level. There is no possibility of paying the workers below that and exploiting them. The reduction in employment is also not possible, as all workers are to be paid the minimum rate.

Those employers who are not in a position to pay a minimum wage will not close down in the short-run. They will try to cover the increased costs by raising the price of the product and pass the burden on to the consumer.

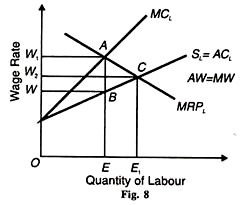

This is possible if the demand for the product is inelastic. Such a situation is explained in Figure 8. Suppose there is monopsony in the labour market and the workers are being exploited by paying them OW wage rate.

To remove exploitation, the government fixes the minimum wage rate at OW2 level whereby the supply of labour is also increased to OE1 with the wage rate. The fixation of a minimum wage between OW and OW1 will, thus, reduce monopolistic exploitation. But a minimum wage above OW1 would reduce employment even below the monopsony level, thereby leading to more unemployment.

Fourth, there is, of course, another side to this problem of minimum wages. If the minimum wage is fixed above the competitive level there will be diminution in employment because profits will fall below normal. Any attempt to raise the price of the product will depend upon its elasticity of demand.

If the demand is inelastic, the wage rise can be passed on to the consumers by raising the price of the product to that extent and the level of employment will not be adversely affected. If, however, the demand for the product is elastic, a rise in the wage level will raise the price of the product and consequently reduce its demand and bring about unemployment.

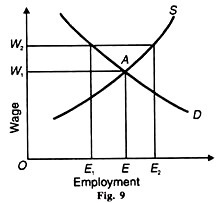

Figure 9 illustrates the effects of fixing the minimum wage above the competitive panel. It shows the determination of the equilibrium wage rate OW1 when the demand and supply curves for labour intersect at point A.

At this wage rate, OE of labour is employed. Suppose the government fixes a minimum wage of OW which is higher than the competitive wage OW1. The increase in the price of labour to OW2 reduces the demand for labour to OE. But the supply of labour increases to OE2 with the fixation of the higher minimum wage. This excess supply over the demand for labour leads to E2—E1 unemployment.

(ii) On Industry:

The fixation of minimum wages may lead to adverse effects on industry:

(a) An industry which cannot afford to pay minimum wages to its workers may close down.

(b) If minimum wages are also fixed for export industries above the competitive level, country’s exports will suffer. For costs rise, profits shrink, output declines and the competitive strength of the industry falls in the face of world competition.

This will not only reduce employment but also the national income If the national minimum wage is fixed above the competitive level, similar results will follow on a much larger scale.

(c) The fixing of minimum wages often leads to the change in its personnel by a firm. If the minimum rate is the same for women and men, men may replace the former or the young may replace the old and the infirm workers.

If, however, special exemptions are granted from the minimum wage to sub-normal or slow workers as is the practice in Australia and England, the firm will employ more such workers and then turn them out when they have to be paid the minimum wage.

(d) It is commonly felt that with the fixation of a national minimum wage, the minimum will become the maximum. Employers already paying more will have the tendency to lower down the wages. They may thus profit from the fixation of minimum wages.

(iii) On Economy:

When the fixation of minimum wages leads to unemployment, rise in costs and prices, and decline in profits and output, these adversely affect the economy.

Conclusion:

As a general principle, there should be a national minimum wage for all employments in the country. I here should be no exception to this rule based even on the capacity of the industry to pay or to meet the export requirements of the country. Neither should there be a rate higher than the minimum for workers of the same category. Such differences can be removed by the state through appropriate fiscal measures.

There is, however, the problem of enforcing the minimum rates where strong trade unions do not exist as in underdeveloped countries. The responsibility for the enforcement of minimum wages therefore devolves upon the labour department and its inspectorate.

It is only when the inspectorate staff is sufficient and honest that minimum wage laws can curtail monopolistic tendencies in underdeveloped countries and raise the productive efficiency of the workers.