After reading this article you will learn about:- 1. Meaning of Externality 2. Types of Externalities 3. Measurement 4. Solutions 5. Pollution Externalities and Economic Efficiency.

Meaning of Externality:

An externality exists when the consumption and production choices of one person or firm enter the utility or production function of another entity without that entity’s permission or compensation (Definition).

An Externality occurs when one persons or firm’s actions affect another entity without permission. If an individual wants to play his stereo loudly, his neighbours must listen as well. Let us understand the term Externality by means of an example, laundry shop and a steel mill.

If a laundry is located next to a steel mill the act of making steel increases costs for the laundry because of all pollution due to the dirt and smoke generated in making steel. Of course there can also be positive externalities. The classic example of externalities is, the owner of an apple orchard provides a positive externality for a neighbouring air (in terms of the quantity and sweetness of the honey).

ADVERTISEMENTS:

An apiary positive externality to the orchard in terms of the bee pollinating the apple blossoms. The generation of knowledge also provides positive externalities in the sense that its benefits are rarely confined to those who generate the knowledge.

Example:

Suppose an individual’s utility function is given by u (x, y) where x and y are quantities of two goods consumed. The individual chooses how much of x is to be consumed but has no control over consumption of y. How much of y will be consumed is chosen by other. This is externality.

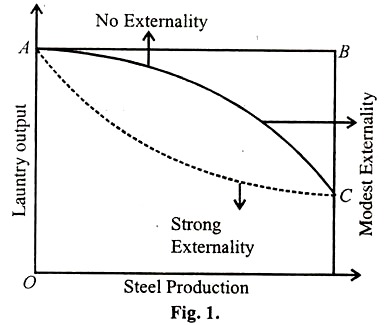

The above diagram illustrates production externality. This shows production possibilities for steel and laundry the maximum amount of the two that can be produced. Note that with no externality both can produce some maximum amount and the two firms are w essentially independent of one another o with a modest externality involved (e.g., smoke). Increased steel production diminished laundry’s output.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If the possible output combinations can even be convex leading to potential pricing problems that will not be explored here. The strength of externality is influenced when the location is proper. The location should be clear and important. As we move two firms away from each other the strength of the externality is bound to decline.

Types of Externalities:

Externalities can be unidirectional or reciprocal which means simply that if A imposed an externality on B and B has not imposed an externality on A, the externality is unidirectional. If B imposed an externality on A as well, then the externalities are reciprocal.

Further classification of externalities is whether they are marginal or intra marginal. If they are marginal and uni-directional then A’s behavior at the margin affects B’s utility or profit. If they are intra marginal, then A can marginally, adjust his behavior without any change in the external effect on B.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This will become clear in the examples of the various types of externalities, which are to follow:

i. A Marginal, Uni-Directional Externality:

An important example is the disutility to pedestrians caused by the emission of exhaust fumes by motor-cars.

ii. Marginal Reciprocal Externalities:

An example of this is when people who enjoy smoking but do not enjoy inhaling smoke that has been exhaled by other smokers respond to other’s smoking by smoking themselves.

iii. An Intra Marginal, Uni-Directional Externality:

A lake may be unsuitable for swimming if too much of certain types of effluents are discharged into it but it may be able to accommodate a large inflow of additional effluents and hence the marginal adjustments in the outflow over a certain range do not alter the extent of the damage.

iv. Intra-Marginal Reciprocal Externalities:

When two radio listener people are in close proximity to each other. On a beach one may be disturbed if the other operates a radio. If each attempts to raise the volume of his radio to overcome the other’s volume then it is possible that, over a range of volumes, their welfare is unchanged.

In this situation the externalities are infra marginal. The absence of the existence of the above—mentioned externality is the precondition in determining the efficiency of perfect competitive market. This has led to the evolution of the concept of market failure.

v. Market Failure in Accounting External Economics:

In the context of environmental economics, the most important source of market failure is the divergence between the producer’s evolution of the costs of his activities and the valuation by society as a whole. This divergence typically arises because of the presence of what are variously called ‘external effect’, ‘spillovers’, ‘neighbourhood effects’ and ‘third party effects’.

A firm’s evaluation of the profitability of alternative levels of output or lines of production is based on the costs of using the inputs required; that is these are the private costs of its activities, borne by the producer or decision-maker himself.

Social costs on the other hand, measure the opportunity cost to society as a whole of the resources used by the firm, where the opportunity cost is evaluated on the basis of the alternative uses which might have been made of the resources. Whenever a producer uses a resource for which society has an alternative use, the social cost of this resource is not zero, even if no price is charged for its use.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The use of rivers to carry away industrial wastes is a conspicuous example of this. Typically, when a factory discharges its wastes into a river, no charge is payable for doing this; the private cost to the factory of using the river, as waste disposal system is zero.

But the resulting pollution may require a down stream industrial user to purify the water he takes from the river before he can use it for his industrial processes; he incurs additional costs as a consequence of the free use of the river by the upstream producer. Further, the contamination of the water may kill fish stocks, and generally degrade its value as a recreational amenity.

In environmental matters there are many examples of the divergence between private and social costs:

1. The atmosphere may be polluted at zero private cost, while the social costs are potentially extremely large, from extra cleaning bills through chest diseases to the unknown implications of any damage to the ozone layer.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. The use of chemical fertilizer gives the farmer the private advantage of improved crop yields; the costs resulting from the accumulation of chemical compounds will be borne by other, possibly far apart in distance and even generations apart in time. It is not only private producers in pursuit of commercial profit who ignore the social costs imposed by their activities.

External effects thus involve the mal-recognition and misdistribution of costs. The adverse consequences for others of a particular activity are not conveyed and priced through an appropriate market transaction.

The implication of this is that the offending activity will be expanded beyond its socially optimal level; where waste disposal is free to the waste producer, he will generate too much waste and devote too few resources to its treatment.

Moreover when the effect has to be rectified by those suffering from them, too many resources will be absorbed, when treatment of dispersed pollutants is more difficult and expensive than at the point of emission.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Externalities may, of course, also be beneficial. The planting of forests may reduce soil erosion over a wide area, and good architecture or effective landscaping gives pleasure, at no charge, to the passerby. In cases where the social valuation of the benefits of an activity exceeds the private valuation the market alone will lead to the activity being underprovided.

vi. Public Goods:

A further area of major relevance to environmental economics, where even a perfect market system would not secure the socially optimal level of provision, concerns what are called collective consumption goods or public goods.

While private goods are supplied on an exclusive basis, only those who are able and wailing to pay the price are being allowed to consume them and consumption by one individual precluding their simultaneous consumption by others, public goods have the reverse characteristics of being non-excludable and non-rival.

Leading examples of collective consumption of public goods are national defence, the eradication of infectious disease, or in the environmental sphere, clean air, landscape amenity and freedom from pollution.

When these are made available to particular individuals they are automatically available to the entire group and use or enjoyment by one individual does not diminish the supply available to others. Public goods can be usefully characterized by the extreme degree to which they imply externalities or spillovers.

Even in a perfect market, public goods will tend to be under provided relative to the social optimum. Producers, in general, will not be willing to supply where they cannot secure payment and payment cannot be enforced where a consumer cannot be excluded from enjoying public goods even if he refuses to pay. While private charity may provide some alleviation, provision will remain insufficient in total and erratic in incidence.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The valuation which people place on public goods is particularly difficult to estimate. The obvious procedure of simulating the market mechanism by finding out the difficulties which narrow self-interest will prompt at least some people to understate their preferences in the hope of avoiding payment.

For example the degree of hostility to the establishment of an airport locally or the support for saving a species of wildlife, cannot be gauged with any degree of accuracy from voluntary contributions to campaign funds at least some actual or potential contributors will reduce their contributions in the knowledge that if the campaign is successful they cannot be excluded from sharing in the benefits of its success, irrespective of their contributions to it.

This is known as the fee-rider problem. It can be moderated by a more enlightened concept of self-interest or a sense of collective social responsibility or more cynically, by balancing the incentive to understatement with an equal incentive to overstatement by under-representing the costs involved, or implying that they will be largely borne by others.

But it is obvious that in many cases an adequate solution to the problem posed by the non-excludability of public goods and the free rider will require public provision with compulsory payment through taxation.

Measurement of Externalities:

One of the problems in developing an optimal environmental policy is that many environmental externalities cannot be measured. Several economists have argued that it is possible to obtain an estimate of the value of, say, clean air, by assuming that the externality is internalized in land values.

By measuring the change in land values coincident with a change in the externality or by relating the spatial distribution of land and property values of differentials over space in the incidence of the externality (other property values determinants held constant) it may be possible to quantify the value of the externality.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The standard method of doing this is to measure the partial relationship between property values (or land rent) and the externality in a multiple regression, regression analysis, drawing upon the ‘hedonic price index’ approach. This approach is based on the hypothesis that a commodity or service cannot be treated un-dimensional but should be decomposed into a set of separate utility-generation characteristics each with its own price.

Nourse (1967) pointed out some of the difficulties involved is estimating the value of clean air with a multiple regression model. The more serious is that higher incomes will boost housing demand (and prices) and will also increase the value of and willingness to pay for clean air. Unless the income elastic ties of demand for housing and for clean air are the same, the estimated co-efficient will be biased.

Solutions for Externality:

i. Solution by Prohibition:

Which suggests total prohibition of the action-giving rise to pollution.

ii. Solution by Direct Controls:

It requires setting a ceiling level of the quantity effluent/emission discharged into water or air, for example in the case of air pollution. Government would have to specify just how much smoke a factory could emit. Direct controls can also be in the form of a specification of the installation of particular pollution equipment.

iii. Solution by Taxes and Subsidies:

Here the idea is to encourage activities that contribute to common goods and discharge those that deviate from common goods. Accordingly a polluter should be required to pay a tax for every unit of waste discharged.

A subsidy on the other hand would require payment of a financial incentive for every unit pollution abated. Subsidy could also be in the form of payment to the firm to cover in part or full the cost of the required pollution control equipment.

iv. Solution through Direct Action:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Solution through direct action by the government in the from of direct investment on sewage investment plants etc.

v. Solution by the Sale of Pollution Permits:

This requires the establishment of a system of marketable licenses. Each license would give its owner the right to pollute up to a specified amount in a given place during a particular period of time. Their licenses could be bought and sold in an organized market.

vi. Solution through Restoration of Property Rights:

It is also suggested by many, who strongly believe that “common property” nature of the resources is responsible for the damages imposed on them. The advocates of this measure believe that restoration of private property ownership will serve as an incentive for preservation and conservation of resources.

Pollution Externalities and Economic Efficiency:

The term external implies that some costs do not accrue to the firm that produces the goods but are imposed on the society. Such costs are outside the market system and are not reflected which pollute the air causing damage to life, effluents discharged into rivers and lakes, making the water unfit for drinking. Of the many kind of externalities we identify only two types: Technological or non-peeuniar externalities and pecuniary externalities.

Pecuniary Externalities:

They are reflected in market prices and do not cause a divergence between marginal private cost and marginal social cost. The change in price caused by the individual decisions which increase the demand and theory of an increase in the cost of production is termed as pecuniary externality. This raise of price is a pecuniary externally.

Dice-economy to the other consumers, if on the other hand the individual decisions cause price to fall, then the phenomenon is a pecuniary to consumer which is a pecuniary economy to seller and vise versa. Pecuniary externalities, befit economy or diseconomy, are reflected in the market prices and hence pose no distortion from optimality.

Real or Technological Economies:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This, on the other hand, prevents the market mechanism from functioning efficiently by laying deviating marginal private cost and marginal social cost on each other. Pollination of water and air are examples technological economies, that imposes an additional cost to the society.

If the externalities are not their the society optimal output is reached when price is exactly such that the marginal private cost = marginal cost. Thus optimal output, when externalities exist is determined when price is equal to marginal social cost.

Marginal Social Cost (MSC) = Marginal Private Cost (MPC) + Marginal External Cost (MEC).

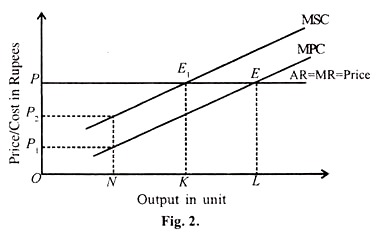

In the diagram Fig. 2. MPC denotes marginal private cost curve of the firm and MSC, marginal social cost that includes external costs as well. P is the price line. The vertical distance between MPC and MSC schedules at any given quantity measures the external cost which is net loss to the society 0 per extra unit of output by the firm.

For example, the MPC of producing ON units of the commodity is OP1 rupees, but the MSC of these units is OP2rupees. The difference i.e., P2-P1 rupees is the marginal external cost of producing the ON units of the commodity of the firm. The marginal external cost of production is constant per unit of output and it does not depend on the level of output.

Since we have assumed perfectly competitive condition in the market, the firm has to take the market price OP. The management of the firm does not take into account of the external cost and as such maximizes profit by equating MPC with price. So in the diagram the firm produces OL units of the commodity, as at this level of output MPC = P and point of equilibrium is E.

But from society’s point of view, all costs should be taken into consideration and the equilibrium point should be at E1 where the firm would be producing only OK units of the commodity and where price = MSC. In an ideal condition, the firm should have P = MSC and production level should stop at OK units.

Private optimal level of production is OL units; but social optimal level of production should be OK units. The difference between the two levels of production (OL – OK = KL) represents over production by the firm. Society would be better off with OK than with OL units because the resources used to produce KL units have greater net productive value in other employments.

The same logic may be applied that in some other goods, production may be below the social optimum level. Thus, we can come to the conclusion that in an ideal competitive market system, external diseconomy distorts the optimal allocation of resources, some goods may be over produced and some in lesser quantities; or they may not be produced at all.