Read this article to learn about the salient features, assumptions, turning points and evaluation of Hick’s theory of trade cycle.

Salient Features:

It is quite true that the principle of acceleration has got quite a few limitations, despite it is accepted as the most effective too) for analyzing the complicated phenomenon of trade cycle.

Professor J.R. Hicks has done a commendable job by analyzing it in his book ‘A Contribution to the Theory of the Trade Cycle’ and showing how far is accelerator responsible for fluctuations and how far trade cycles can be explained in terms of accelerator.

He tries to provide a more adequate explanation of the trade cycles by combining the multiplier and the accelerator.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

In the cycle theory presented by Hicks’, growth is all important: Hicks holds, as does Harrod, that we must approach the business cycle as a problem of an expanding economy. That is to say, we must study not fluctuations merely, but fluctuations as they take place about a rising trend. In this way, Hicks’ model of the trade cycle represents an important step towards integrating a theory of cyclical fluctuations with the factors of economic expansion.

He bases his model on the saving-investment relation, the acceleration principle and Harrod’s notion of the cycle as a problem of an expanding economy. The process of expansion is explained in terms of the multiplier and accelerator which operate with a time lag. According to him, “the theory of the acceleration and the theory of multiplier are the two sides of the theory of the fluctuations, just as the theory of demand and the theory of supply are the two sides of the theory of value.”

Hence, autonomous investment, which to Hicks represents the growth factors due to increase of population and the progress of technology, plays a significant part in the determination of the cycle. Thus, the useful concepts which play an important part in Hicksian model of trade cycle are the warranted rate of growth’, induced and autonomous investment and the relation of the multiplier and the accelerator.

A distinction is made between autonomous investment and induced investment—the latter is a function of changes in the level of output and the former a function of the current levels of output. Under autonomous investment Hicks includes “public investment, investment which occurs in direct response to inventions and much of the ‘long range’ investment (as Harrod calls it) which is only expected to pay for itself over a long period.”

ADVERTISEMENTS:

He assumes that investment increases at a regular rate so that it remains in progressive equilibrium if it were not disturbed by extraneous forces. On the other hand, induced investment depends upon change in the level of output or income and is a function of an economy’s growth rate.

Hicks agrees that, whereas, the monetary mechanism may greatly influence the course of the cycle, the fundamental causation of the cycle lies in the multiplier-accelerator relationship, and expect in rare instances, the effective ceiling is the full employment level and the effective floor, the trend levels of autonomous investment.

In short, according to Hicks, trade cycle is an explanation in real terms of a mechanical technological sort in which monetary factors are left out or admitted as a modifying factor and where, apparently, human judgment or varying business expectations and decisions play little or no part. Investment plays the leading role but is based on formula, not judgment. This would appear as the most serious limitations of such a theory.

Assumptions:

The following assumptions were made to develop his theory of the trade cycle:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(i) In Hicksian analysis, a progressive economy is assumed in which autonomous investment is increasing at a regular rate, so that system is such which could remain in progressive equilibrium.

(ii) The saving and investment coefficients are such that an upward displacement from the equilibrium path will tend to cause a movement away from equilibrium, though this movement may be lagged.

(iii) There is no direct restraint upon upward expansion in the form of a scarcity of employable resources provided by the full employment ceiling i.e., it is impossible for the output to expand beyond full employment level.

(iv) Though there is no direct constraint on the contraction yet the transformation of accelerator in the downswing (i.e., disinvestment cannot exceed depreciation) provides an indirect constraint.

(v) There are fixed values of the multiplier and accelerator throughout the different phases of a cycle, i.e., consumption function and investment function are both assumed to be constant.

(vi) However, in Hicksian analysis both the multiplier and accelerator are treated with a lag. He treats multiplier as a lagged relation, so that consumption in period t is regarded as a function of income of the previous period t – 1 and not of current period t. He also uses accelerator with a time lag i.e., induced investment in present period also responds to output changes in the previous period.

Upswing Downswing—Upper and Lower Turning Points:

In the upswing of cycle income rises as a result of the combined action of the multiplier and accelerator. A super cumulative process of income propagation and investment expansion based on the ‘interaction’ of the multiplier and accelerator is attained in the economy called ‘leverage effects’. These two tools of multiplier and accelerator work hand in hand to make expansion cumulative in character.

This continues till the economy touches the ‘full employment ceiling point’. In a dynamic economy, there will be an expanding or rising ceiling and, therefore, it may take much longer than in a static set up to reach the ceiling but once the ceiling is touched the cycle takes the downward swing.

The upper turning point of income is determined by the availability of resources like population, technology, capital stock, etc. The process of expansion hits against the ceiling and turns down or in some cases when the interaction of the multiplier and accelerator is not strong enough, the downswing starts even before the ceiling is touched. The decline in investment in the downswing also operates cumulatively but the decline cannot continue indefinitely because of the lower limit which depends upon the fact that gross investment cannot fall below zero.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

At the lower level, some essential and basic investment for replacing inventories and equipment becomes inevitable; the autonomous investment starts asserting itself once more at this stage and is higher than the amount of disinvestment. The increment of net investment causes an upturn of aggregate income and takes the economy along an upward phase. Hicks has expressed the opinion that while the upswing is the result of the interaction of multiplier and accelerator, the downswing is largely a product of the multiplier (the accelerator remaining inoperative for the most part).

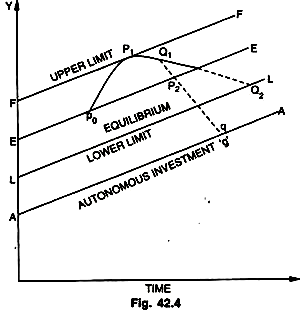

Thus, the lower turning point during depression is caused when the amount of disinvestment turns out to be less than the amount of autonomous investment, so that, there is increase in net investment turning the cycle on a path to prosperity. Hicks theory of the cycle is shown in the Fig. 42.4.

1. In this figure Line AA shows autonomous investment, which is assumed to be growing at a constant rate ‘g’.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

2. EE shows the equilibrium path of output which depends upon AA and is deduced by applying ‘super multiplier’ to it.

3. LL represents the lower equilibrium path of output or floor or bottom or lower limit.

4. FF represents the full employment ceiling showing maximum expansion when scarcity of resources occurs. It is supposed to be above the equilibrium path EE and is assumed to grow at the same rate at which AA is growing.

Up to P0 the economy moves along equilibrium path of output and employment EE. Suppose at P0 there is a burst of autonomous investment following, say, an invention. This will cause a disturbance and the path of output moves steadily away from EE to FF. This happens despite the fact that although the burst is short lived and may be over and autonomous investment falls back to its old level, yet on account of explosive S and I coefficients (as assumed above) the multiplier and acceleration interaction takes the economy from P0 to P1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

However, the upward expansion cannot continue indefinitely and must finally reach the ceiling FF at some point as P1. As soon as the expansion of output hits the point P1 the cycle reaches the top of the boom and the output hits the hump. It has got to come down but it does not fall with a crash immediately but creeps along the ceiling for some time on account of lagged effects and adjustments of induced investments.

After creeping along for a while and it will creep as long as the lagged effects of induced investments are there; afterwards it moves down and the downward trend of cycle begins. But once the output starts falling it can no longer remain even along the equilibrium path EE.

Once a fall starts it is interesting to note that it does not halt at the equilibrium level on account of the effects of past investments and because current investments are below the level at which output can be maintained at equilibrium level, hence the fall doesn’t stop at equilibrium level and it moves down.

Now, the downturn is not abrupt or sudden or quick as shown in Q1P2q without any floor or bottom but slow and gradual along Q1P2q with a bottom beyond which it cannot go because the multiplier is less than unity and accelerator (or disinvestment) is limited by replacement or depreciation— so it must have a floor.

Hick has shown that the downward trend of the accelerator is not the same as upward, while moving up it goes very fast. In fast on the downward path, there is a change in the working of the accelerator. If upward and downward functions of accelerator were the same, economy would have a steep fall along Q1P2q; but in reality since disinvestment is limited by the rate of depreciation, the fall in output is slower but prolonged as indicated by Q1Q2 (Investment now consists of autonomous investment minus the constant rate of depreciation).

Since gross investment cannot fall below zero, the fall in output cannot go on indefinitely as in Q1P2q. The slump must have a bottom which is provided by EL. After it reaches LL it does not go up immediately, but it creeps along LL for some time on account of the existence of excess capacity. Once this excess capacity is exhausted, the positive acceleration effect becomes operative again and the cycle will be repeated.

Evaluation:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Thus, we find that Hicks provides a satisfactory explanation of turning points of trade cycle through accelerator and also sheds light as to the periodicity of the cycle which may not be regular. Since the system has a hump or a ceiling and a floor or a bottom it must oscillate between these two limits like the pendulum of a clock. Hicks by showing how the excess capacity delays the upswing make an important contribution to the theory of trade cycle. Hicks model, while highly simplified as presented here serves as a useful framework of analysis, which with modification, yields a fairly good picture of cyclical fluctuation within a framework of growth.

It serves specially to emphasize that, in a capitalist economy characterized by substantial amounts of durable equipment, a period of contraction almost inevitably follows expansion. His model also pinpoints the fact that in the absence of technological development and other powerful growth factors, the economy will tend to languish in depression for long periods of time.