Let us make an in-depth study of the Permanent Income Hypothesis:- 1. Subject-Matter of Permanent Income Hypothesis 2. Reconciliation 3. Criticisms of the Permanent Income Hypothesis 4. Policy Implications of the Permanent Income Hypothesis.

Subject-Matter of the Permanent Income Hypothesis:

Under the relative income hypothesis, current consumption depends on current income relative to previous peak income.

Consequently, current consumption depends on more than current income.

This is also true in the case of the permanent income hypothesis developed by Milton Friedman.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Under the permanent income hypothesis, current consumption depends on current income and anticipated future income. This view is intuitively plausible. For example, if a household receives current income which is appreciably less than it anticipates in the future, the household is likely to consume more than is suggested by the level of its current income.

Friedman’s permanent income hypothesis is based on three fundamental propositions. (I), a household’s actual income, v, and consumption, c, in a particular period may be separated into permanent and transitory components. In other words,

y=yP + yt

and c = cp + ct

ADVERTISEMENTS:

where the subscripts p and t stand for permanent and transitory, respectively.

According to Friedman, permanent income is the amount a household can consume while keeping its wealth intact. By wealth, Friedman means the present value of the income expected to accrue to the household in the future. Since permanent income is, in part, based on the household’s anticipated future income, it is a long run concept.

Since permanent income depends on future income, it cannot be measured directly. In his empirical work, Friedman regards permanent income as a weighted average of current and past incomes, with the current year weighted more heavily and prior years weighted less and less heavily, it is less variable than current income.

Transitory income may be interpreted as unanticipated income; it may be either positive or negative. For example, farmers may receive more income than anticipate because of unusually good weather, or they may receive less income because exceptionally bad weather. Similarly, an individual may earn less than anticipate because of illness.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If a household’s transitory income is positive, its actual income exceeds its permanent income. On the other hand, if its transitory income is negative, the reverse is true. By its nature, transitory income is regarded as temporary.

According to Friedman, a household’s actual consumption may also be divided into permanent and transitory components. Permanent consumption is consumption determined by permanent income. Transitory consumption may be interpreted as unanticipated consumption, such as unexpected doctor bills, unusually high (or low) heating bills, and the like.

Transitory consumption, like transitory income, may be either positive or negative. If it is positive, a household’s actual consumption is greater than its permanent consumption. If it is negative, the opposite is true. Like transitory income, transitory consumption is regarded as temporary. Friedman assumes that permanent consumption is a constant proportion, n, of permanent income.

In equation form,

cp = nyp (0 < n < 1).

Although n is independent of the absolute level of permanent income, it depends on the interest rate and a number of other variables. Friedman assumes that there is no relationship between transitory and permanent income, between transitory and permanent consumption, and between transitory consumption and transitory income. The first assumption implies that transitory income is random with respect to permanent income; the second implies that transitory consumption is independent of permanent consumption.

The last assumption—that transitory consumption is random with respect to transitory income—implies that the marginal propensity to consume from transitory income is zero. This means that a household fortunate enough to receive positive transitory income will not alter its consumption (which is based on permanent income). Instead, the household will save the additional income. Similarly, if a household is unlucky enough to receive negative transitory income, it will not reduce its consumption. Rather, it will reduce its saving.

At first glance, the assumption of a zero marginal propensity to consume from transitory income appears naive, at least in the case of positive transitory income. After all, if a household receives a windfall, it seems likely that its consumption will increase. Friedman and others have argued that the purchase of durable goods should properly be regarded as investment rather than consumption.

The reasoning is that durable goods, by definition, are not consumed during the year in which they are purchased. Instead, they provide a How of services over a number of years. If only the value of services rendered per year is counted, the assumption of a zero marginal propensity to consume from transitory income is more plausible.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Based on the three propositions, a household is assumed to plan its consumption on the basis of its permanent income with permanent consumption equal to a constant proportion, n, of its permanent income. Consequently, under the permanent income hypothesis, the basic relationship between consumption and income is denoted by the long-run consumption function.

The Reconciliation:

To reconcile the short- and long-run consumption functions using the permanent income hypothesis, consider the economy over the business cycle. The nation’s output increases over time. But output does not grow at a steady rate; if often reaches a peak and then declines. These fluctuations in output and economic activity in general are called business cycles. When output is at its highest level, the business cycle is said to be at its peak. When output is at its lowest level, the business cycle is at its trough.

Since permanent income is a long-run concept, it does not vary to the same degree as actual income over the business cycle. Consequently, when the business cycle is at its peak, actual income is greater than permanent income. Since actual income is greater than permanent income, transitory income is positive.

Since the marginal propensity to consume from transitory income is zero, households do not alter their expenditure plans. Consequently, consumption is not proportional to actual income at the peak; it is less than proportional, thereby producing a point on the short-run consumption function which is below the long-run consumption function.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

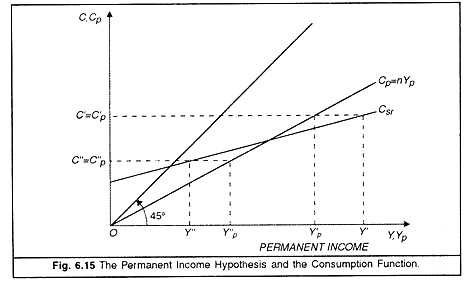

To illustrate, suppose Y’ in Figure 6.15 represents income at the peak of the business cycle. With permanent income less than actual income at the peak, assume that Yp represents the corresponding level of permanent income. Since consumption is determined by permanent income, consumption is C = Cp‘ at permanent income Yp’8. In as much as the short-run consumption function is based on actual consumption and income, (Y’, C’) is a point on the short-run consumption function.

At the trough, the situation is reversed. Actual income is less than permanent income, negative.

Since the marginal propensity to consume from transitory income is zero, households do not reduce their consumption. Instead, they reduce their saving. As a result, consumption is more than proportional to actual income, thereby producing a point on the short-run consumption function which is above the long-run consumption function.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

To illustrate, suppose Y” and Y”p represent respectively the actual and permanent levels of income at the trough. Since consumption is determined by permanent income, consumption of C” = Cp” and (Y”, C”) is another point on the short-run consumption function.

In simplest terms, the short-run consumption function, a relationship between actual consumption and actual income, exists because of deviations between actual and permanent income. Since permanent income is a long-run concept, actual income varies to a greater degree than permanent income. In as much as consumption is based on permanent income, consumption varies to a smaller degree than actual income. These smaller variations in consumption produce the relatively flat consumption function that is observed in the short run.

Criticisms of the Permanent Income Hypothesis:

Although much empirical evidence supports the permanent income hypothesis, evidence also exists which contradicts the hypothesis.

Criticism of the hypothesis has centered on two main assumptions:

(1) The assumption of a constant average propensity to consume;

(2) The assumption of a marginal propensity to consume from transitory income equal to zero.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Among others, Irwin Friend and Irving B. Kravis have objected to Friedman’s assumption of a constant average propensity to consume. They contend that households with low levels of permanent income arc under much heavier pressure to consume than households with much higher levels of permanent income.

Therefore, from a theoretical standpoint, the average propensity to consume of low-income households should exceed that of high-income households. Thus, Friend and Kravis claim that the average propensity to consume declines as permanent income increases.

Many economists have also objected to Friedman’s assumption of a marginal propensity to consume from transitory income equal to zero. Empirically, much evidence suggests that the marginal propensity to consume from transitory income is positive. The early empirical studies involved analysis of the impact of windfall income. These studies suggest that moderate increases in consumption are associated with the windfall income.

More recent studies suggest that the marginal propensity to consume from transitory income is larger than that suggested by the early studies. The same studies also suggest that the marginal propensity to consume from transitory income is less than the marginal propensity to consume from permanent income.

From an empirical point of view, this hypothesis is hard to test because of the difficulty of measuring permanent income and permanent consumption. Consequently, debate continues on the merits of this hypothesis (as well as other hypotheses). There is, however, a consensus that the permanent income hypothesis, broadly interpreted, is valid.

Policy Implications of the Permanent Income Hypothesis:

The implications of the permanent income hypothesis differ from those of the absolute and relative income hypotheses. Those hypotheses made no distinction between permanent and transitory income. Consequently, households are assumed to react in the same manner regardless of the type of increase in income. According to the permanent income hypothesis, households base their consumption on permanent income rather than actual income. Consequently, they will react in different ways, depending on whether they regard an increase in income as permanent or transitory.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

If households receive an increase in income which they interpret as an increase in permanent income, they would increase their consumption by an amount proportional to the increase in income. On the other hand, if households interpret the increase in income as transitory, they would not increase their consumption at all.

In terms of multiplier analysis, this means that since the marginal propensity to consume from permanent income is high (Friedman estimated it to be 0.88), the multipliers (assuming the change is viewed as permanent) will be relatively large, larger in fact than suggested by the short-run consumption function. Similarly, since the marginal propensity to consume from transitory income is zero, the multipliers (assuming the change is viewed as temporary) will be small or even zero.

If either the absolute or the relative income hypothesis is valid, it makes no difference whether a change in taxes is permanent or temporary. A tax rebate or a temporary change in taxes maybe desirable in order to provide prompt and temporary stimulus or restraint to the economy. For rebates or temporary tax changes to be effective, however, a relatively large change in consumption must occur within a short time span following the rebate or change in taxes.

According to the absolute and relative income hypotheses, the changes in consumption will be large and occur within a short time span. If the permanent income hypothesis (or a similar hypothesis, such as the life cycle hypothesis) is valid, the changes in consumption will be small and occur over a relatively long time span. Consequently, the success of temporary policies largely hinges on whether households react differently to temporary changes.

In the United States, the fiscal authorities have used tax rebates and income tax surcharges on several occasions. In 1975, a tax rebate was given. The rebate was designed to increase consumption, thereby stimulating the economy. In 1968, a temporary 10 percent income tax surcharge was imposed. The tax increase was designed to reduce consumption or at least slow its rate of increase, thereby reducing inflation. Tax rebates have been proposed upon other occasions.

Franco Modigliani and Charles Steindel have examined the effects of the 1975 tax rebate upon consumption. In general, they found that the rebate results in appreciably smaller increases in consumption than those associated with a permanent tax reduction of equivalent size. They also found that the increases in consumption occurred less rapidly.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

Modigliani and Steindel also considered the effects of the 1968 income tax surcharge upon consumption. They believe that the surcharge, in effect for most of the 1968-70 period, reduced consumption. The reduction, however, was appreciably less than would have occurred in the case of a permanent tax increase or equivalent size. As a result, the surcharge was relatively effective in curbing inflation.

Thus, the permanent income hypothesis and the empirical evidence suggest that rebates and temporary changes in taxes are relatively ineffective in altering consumption and hence aggregate demand. Since the empirical evidence also suggests that rebates and temporary tax changes are not completely ineffective, such actions may play a useful role in stabilizing the economy. For one thing, the US Congress is apparently much more willing to legislate temporary tax changes than permanent changes. For another, the smaller multipliers associated with rebates and temporary tax changes can be offset by making the rebates or tax changes larger.