The following article will guide you about how the product market adjusts.

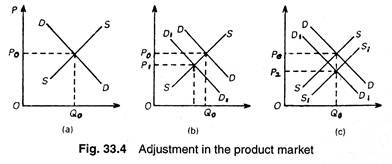

Equilibrium in a typical product market of which there are many in the economy, is shown in part(a) of Fig. 33.4. The intersection of the product demand curve (DD) and the product supply curve (SS) determine the equilibrium price P0 and equilibrium output Q0.

A fall in aggregate demand is reflected in a leftward shift in product market demand curves throughout the economy. This is shown in part (b), where the aggregate demand curve shifts to the left to D1D1.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

The equilibrium price falls from P0 to P1 and the equilibrium output from Q0 to Q1.This also occurs in other product markets. Producers now cut back output and reduce their employment of labour and the purchase of other resources.

The redundant workers are now involuntarily unemployed because they are willing to work at the yet unchanged wage rates. They will, therefore, compete for the available jobs by bidding down wages. Similarly suppliers of raw materials will lower their prices to reduce their surpluses.

The lowering of wages and factor prices causes product market supply curves to shift rightward. This process continues until the initial output levels in product markets are restored and all available workers are once again fully employed.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

This is shown in part (c) where the product market supply curve has shifted from SS to the position S1S1. The initial output of Q0 is restored but at a lower equilibrium price P2, determinant by the intersection of D1D1 and S1S1. The economy is once again operating at full employment output level. Wage-price flexibility would always ensure this result.

So to conclude, however, the classical system depends upon three central propositions:

ADVERTISEMENTS:

(a) S and I depend on the rate of interest;

(b) Wages, prices and interest rates are flexible; and

(c) The economy is characterized by competitive forces in both product and resource markets.

Given these conditions, there would be neither deficiency of aggregate demand nor over-production. The end result would be full employment. The Great Depression challenged the classical model of self regulating markets, Say’s Law, and the quantity theory of money with the reality of prolonged depression and unemployment.

Business cycle theorists had failed to either identity the weaknesses of the classical model or come up with an adequate alternative model.

In The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money (1936), Keynes did both. He criticized all the elements of the classical model and offered an alternative view of the way the world works.

This alternative view was the basis for the Keynesian revolution, the shake-up in macroeconomic ideas that resulted from Keynes’ challenge to classical theory and presentation of an alternative explanation of how employment (output) is determined.

The Keynesian alternative begins with the aggregate demand curve and works from there to employment, instead of the other way around.